Darwin's long marriage to Emma Wedgwood is well documented, but was there an earlier romance in his life? How was his departure on the Beagle entangled with his first love? The answers are revealed in a series of flirtatious letters that Darwin was supposed to destroy.

Burn this as soon as read-or tremble at my fury and revenge-

Had nineteen-year-old Darwin followed this instruction in a letter he received in 1828, there would be little trace of his romantic relationship with 'the prettiest, plumpest, Charming personage that Shropshire possesses'. This personage, a certain Miss Fanny Mostyn Owen, wrote a series of revealing letters to Darwin, giving glimpses into their relationship, the gifts they exchanged, and what Darwin's hopes might have been regarding Fanny when he embarked on the Beagle voyage. We do not know whether Fanny burnt the letters she received from Darwin, but he carefully kept the letters he received from her to the end of his life.

The Mostyn Owen and Darwin families were friends, and Darwin was regularly invited to shoot with Fanny's brothers at Woodhouse, the Mostyn Owen estate in Shropshire. He was a great favourite of Fanny's father, William Mostyn Owen, 'the Governor'. Darwin first heard about Fanny when he was an undergraduate at Edinburgh. She soon became one of the main attractions of Woodhouse.

The high-spirited, fun-loving Fanny, two years older than Darwin, clearly established the terms of their relationship. Her vivacious, flirtatious tone, her love of the dramatic, and most of all her inclusion of Darwin in a make-believe private world, were most likely inspired by her knowledge of Gothic novels with their mix of the supernatural, terror, romance, and history. We know she read Ann Radcliffe's Mysteries of Udolpho, but it was probably Radcliffe's The Romance of the Forest that shaped the relationship she developed with Darwin. The characters include Peter, a postilion, and Annette, a housemaid, who flee with their employers (who are escaping creditors) to a ruined abbey in a forest. In Fanny's first letter, and in many others she wrote to Darwin, he was postilion to her housemaid, and Woodhouse was The Forest.

Fanny's teasing and familiar tone, as well as her enjoyment of malapropisms and made-up words, convey a warmth of character that was first noted by Darwin's sister Catherine. After staying a week at Woodhouse in 1826 as company for Fanny and her older sister, Sarah, both recently back from France, Catherine wrote to Darwin in Edinburgh. 'I never saw such merry, agreeable girls as Fanny and Sarah are', she reported, 'talking so easily and naturally, and so full of fun and nonsense- They are very much admired, and get plenty of partners at the Balls; but they are not at all more reconciled to England, and are longing to return to France.' Fanny did not return to France, but she indulged to the full in all the aspects of social life open to her.

![Letter from Fanny Owen, [late January 1828] (DAR 204: 43)](/sites/default/files/20200929_145807c.jpg)

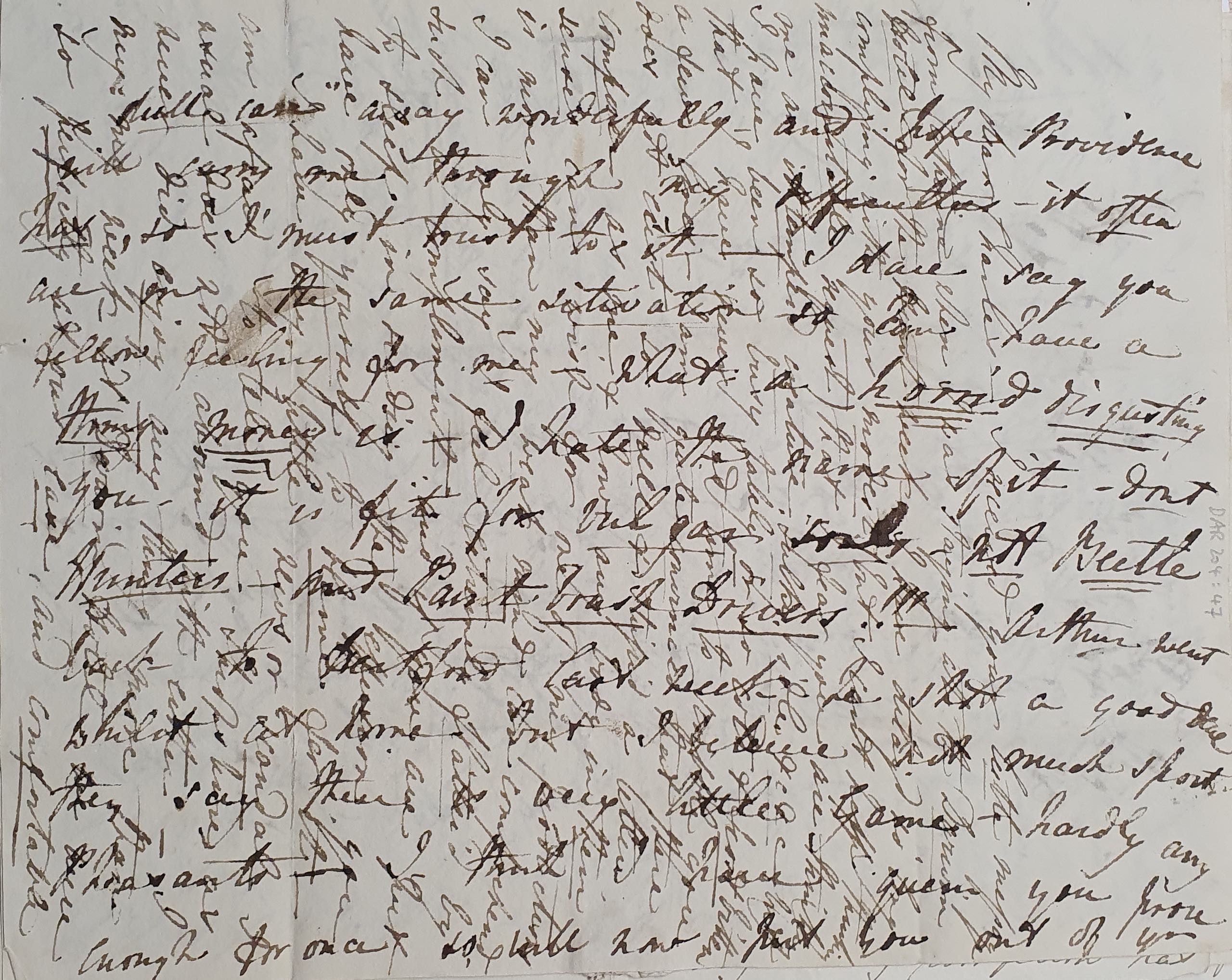

First and last pages of the letter from Fanny Owen, [late January 1828] (DAR 204: 43). Her 'crossed' letters are typical of the period when expensive postage charges were based on the number of pages and distance. Instead of using two pages (which would double the cost), writers turned their paper 90 degrees and wrote over the first set of writing. Before the Penny Post (1840), envelopes were rarely used. Instead, the letter was folded and held shut with sealing wax. The recipient paid the postal costs.

Scandal and mystery

Fanny's first letters to her 'dear Postillion' were sent while she and her older sister, Sarah, were visiting Brighton in January 1828 and attending balls and parties almost every night. They show how she inhabited her imagined persona and craved excitement. Thriving on the social life of Brighton, she also demanded that Darwin send her 'Shrewsbury scandal'. 'You well know if the Ho<use>maid has a foiblesse it is for a mystery', she told him, adding that she hoped he would still be in Shrewsbury on her return, and that she expected 'cart loads of black mysteries after so long an absence'.

Darwin, however, did leave Shrewsbury before Fanny's return, following his father's decision that he give up studying medicine at Edinburgh and instead go to Cambridge University with the aim of becoming a clergyman. Fanny's slow response to the news of Darwin's departure came with the excuse that she had not written sooner because 'that word Cambridge sounded most formidable to my ears'.

I had visions of Mrs. Burton [the vicar's wife] constantly starting up before me, which seemed to say, "Dear me Ma'am would you believe it Miss Fanny Owen corresponds with a young man Ma'am at the University" this horrid phantom appear'd to me so often and worked upon my heated fancy to such a degree that after mature deliberation I thought it best to remain silent and if the Postillion should be in a fury at my ingratitude to explain it all away when we shall meet once more at the Forest-& now you see Mrs. Burton has been the cause of all this I hope you will forgive the poor Housemaid-

As she signed off, Fanny emphasised their make-believe world by claiming that she 'never could write like any thing but what I am, a Housemaid'. Darwin's feelings were probably more straightforward and ardent, and he had evidently asked why he had not heard from her.

Writing before the end of Darwin's first Cambridge term, Fanny complained she had 'not a whisper, not the ghost of a mystery' worth retailing. Despite describing various 'brilliant' social events and poking fun at those attending them, she felt she was 'getting awfully dull and prosy'. She closed her letter with instructions to 'burn this, or if it falls into the hands of any of the young men, what would they think, of a Housemaid writing to Mr Charles Darwin-' That summer, while away from Woodhouse, Fanny begged him to send news.

A gift with wings

At Cambridge, Darwin's new-found passion for entomology expressed itself in a gift for Fanny. He sent her a swallowtail butterfly (one of the rarest and most spectacular of British butterflies, whose habitat in the nineteenth century included Cambridgeshire fenland).

Swallowtail Papilio macheon. © Iain H. Leach. (https://www.iainleachphotography.com)

Fanny's thanks came in a characteristic letter. Apologies for not writing sooner, were followed by her description of going to the theatre in Oswestry the evening before, her account as dramatic as the play itself:

it was quite a miracle that we persuaded Papa to let us go knowing his antipathy to that kind of hinnocent amusement, but the wonder ceased when we found that the gay, dashing handsome, dissipated General Despard [83 years old] was the only shootable in the Play House - We went six inside the family Van, your two sisters, Mrs. Parker who is very corpulent and we three only fancy what a suffocation! I really thought some valuable lives would have been lost … but happily all escaped uninjured, and very good fun and plenty of laughing we had-but it is brutal to tell you all this-

Perhaps more brutal was her forgetting the purpose of her note until this point; 'better late than never', she declared herself 'very much oblig'd' for Darwin's gift. The swallow tail 'has absolutely astounded my weak mind, there is something about it so werry pecoolier', she told him, before complaining that since his return to Cambridge, she had not played billiards or gone riding.

When Darwin did not return to Shrewsbury for Christmas 1829, though she had 'fully expected' to see him, she supposed 'some dear little Beetles, in Cambridge or London kept you away- I know when a Beetle is in the case every other paltry object gives way -if I could have sent to tell you I had found a Scrofulum morturorum perhaps you might have been induced to come down!- how does the mania go on, are you as constant as ever?' In this letter, the postilion and housemaid are displaced by monikers that denoted their current interests. Deploring her diminished finances after Christmas, she exclaimed 'What a horrid disgusting thing money is-I hate the name of it-dont you-it is fit for vulgar souls -not Beetle Hunters -and Paint brush Drivers!!!' Darwin was still as enraptured as ever by the Owens of Woodhouse, whom he thought of as the 'idols of my adoration', especially 'la belle Fanny'.

Letter from Fanny Owen, 27 January [1830] (DAR 204: 47), referring to Darwin as a Beetle Hunter and herself as a Paint brush Driver.

A long voyage and a secret ride

In the end, it was Darwin's 'mania' for natural history that led to his separation from Fanny. On hearing that Darwin wished to say goodbye to her before departing on the Beagle voyage, Fanny expressed her intense regret that she was away in Devonshire. 'My dear Charles I do hope you will enjoy yourself & be the happiest of the happy, I would give any thing to see you once more before you go, for it does make me melancholy to think the time you are to be away'. She wished she had made him pincushions so that 'occasionally in taking out an instrument of death for a Beetle' he 'would have called to mind the Manufacturer of the useful article'. Instead, she sent him a purse, which she hoped would remind him of 'the Housemaid of the Black Forest'. Shortly after this, she was dismayed to learn that the voyage was to last three and not, as she had heard, two years, but she reassured Darwin that she would remember him. Responding to a recent letter he had written in a 'Blue devilish humour', she wrote:

In her last letter before the Beagle sailed, she wrote, 'You cannot imagine how I have missed you already at the Forest, & how I do long to see you again … how I do wish you had not this horrible Beettle taste you might have staid "asy" with us here I cannot bear to part with you for so long'.

Little wonder that Darwin felt bereft when he learned in a letter from his sister Catherine, received four months later in Rio de Janiero, that within twelve days of the Beagle sailing, Fanny was engaged to Robert Myddelton Biddulph of Chirk Castle. 'I hope it won't be a great grief to you, dearest Charley', was the only consolation Catherine could offer. 'If Fanny was not perhaps at this time Mrs Biddulp, I would say poor dear Fanny till I fell to sleep', Darwin replied from Brazil, adding, 'I feel much inclined to philosophize but I am at a loss what to think or say; whilst really melting with tenderness I cry my dearest Fanny'.

Romantic to the last, Fanny had accepted Robert's proposal of marriage in 'the course of a secret ride'. Behind this, however, lay doubts. Fanny had already been jilted once, and Biddulph had to prove himself to the Mostyn Owen family, having had a flirtation with Fanny's sister Sarah the previous summer. Darwin's sister Catherine thought him 'a dissipated, gambling character'[154], and did not believe Fanny cared for him as much as her previous suitor. By the time Biddulph had decided on the financial arrangements of the marriage settlement, Fanny (so Darwin heard from his sister Susan) had 'very much lost her former housemaid spirits'.

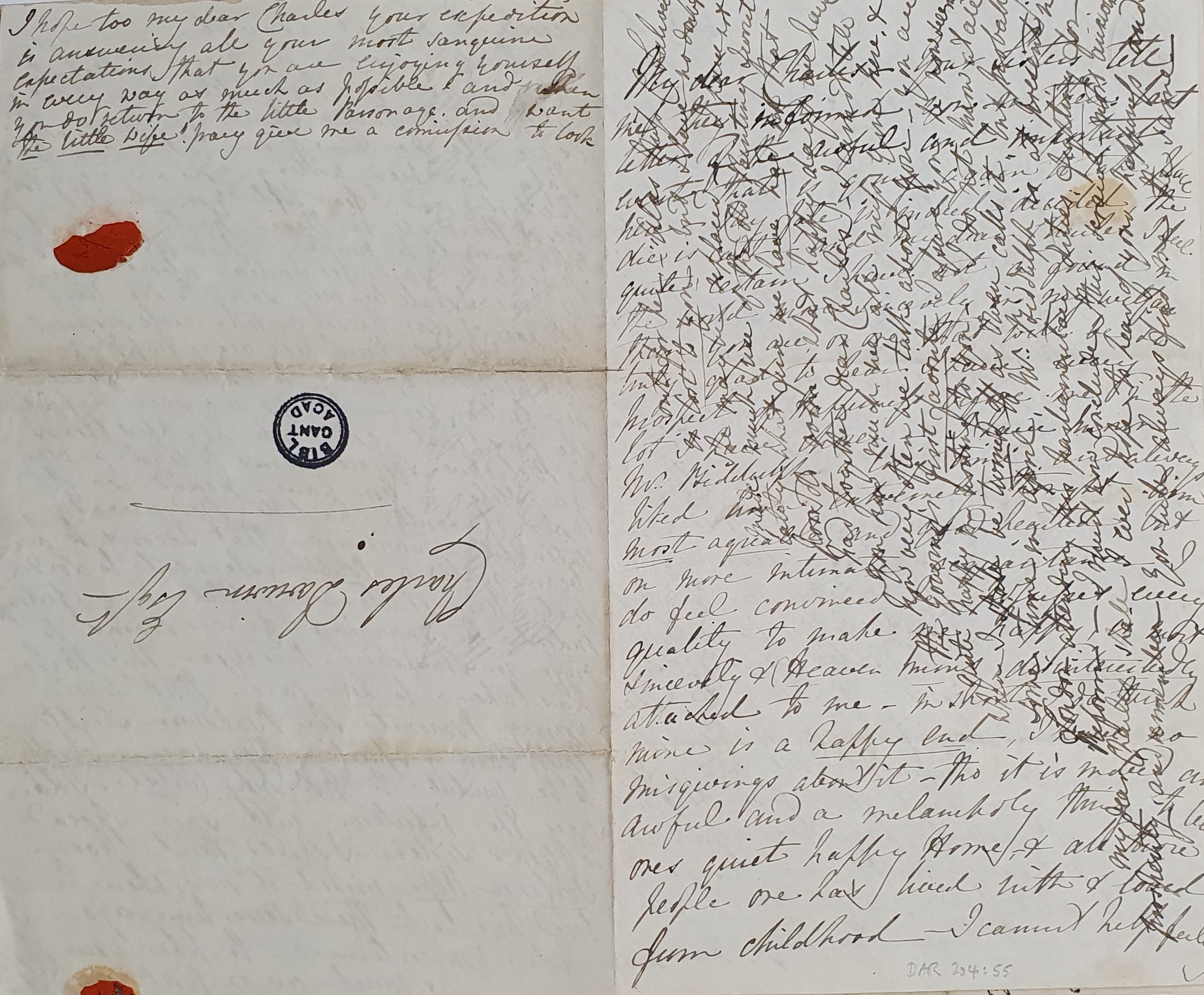

The first and last pages of Fanny Owen's letter of 1 March 1832 (DAR 204:55), in which Fanny told Darwin of her forthcoming marriage to Robert Myddelton Biddulph, whom, she thought, possessed 'every quality to make me happy'.

Darwin's delight in the world created by Fanny Owen in the forest of her own imagination, probably would not have culminated in marriage. The next time Darwin was writing love letters, the context was closer to the more rational, pragmatic world portrayed by Jane Austen, where successful marriages, even when feelings ran high, were not rapidly arranged in secret meetings on horseback, but after careful consideration. Two years after his return from the Beagle voyage, and following a deliberate weighing up the pros and cons of marriage, Darwin decided to propose to his cousin Emma Wedgwood. Their engagement letters focus on daily events, their religious differences, the practicalities of house hunting in London, the tiresome business of hiring servants, and the removal of a dead dog from the garden of the house they finally settled on. This was real life. Perhaps Darwin's love for Fanny was so exciting because it was always fantasy.

Did they all live happily ever after?

Apart from one brief visit on his return from the Beagle voyage, when Fanny was unwell and about six months pregnant with her third child, Darwin never saw her again. During the last months of the voyage, he had been warned that she was looking 'wretchedly ill & thin', and that he 'would hardly know her she is so altered from the robust girl she was formerly'. We do not know what Darwin thought when he met her in late 1836, but Fanny was touched by his visit and gift of flowers. She had clearly wished to see him, as Susan Darwin had reported while visiting Woodhouse in early 1835.

The Darwin sisters agreed that the saving grace of the 'very handsome & gentlemanlike' Robert Myddelton Biddulph was his fondness for Fanny, but their assessment of his character was not flattering. Although Fanny seemed 'happy & attached to Mr. B', Caroline Darwin couldn't help thinking, though she had 'no great proof', that he was 'a very selfish man' and 'a tiresome person to live with.' Catherine remained the most sceptical. 'Poor Fanny will not have a very pleasant or easy life I am afraid', she told Darwin just two months after Fanny's marriage, 'the old Mother, Mrs Biddulph is so odious to her, and Mr Biddulph is such an exacting Husband.' After the excitement of helping Robert successfully canvass for election as Whig MP for Denbighshire in 1832, Fanny was able to escape Chirk Castle (and her 'stiff & formal' in laws) to accompany him to London while Parliament was sitting. However, following the birth of her first daughter in May 1833, she was 'deplorably ill & weak, and very lonely'. 'MrBiddulph seems fond & affectionate to her,' Catherine reported, 'but he is a gay dissipated man, and desperately selfish also.' Nonetheless, as William Mostyn Owen commented when he wrote to Darwin during the Beagle voyage, Fanny had made 'what the world calls a very great match'.

One last opportunity arose for Darwin to see Fanny in 1880, but he was thwarted. Eight years earlier, Darwin had renewed his connection with Fanny's older sister Sarah, then living in Richmond, when he sent her a copy of his newly-published book The expression of emotions in man and animals, perhaps because he recalled her interest in animals. Sarah had also been part of the attraction of Woodhouse for Darwin, but more as a friend and confidante, the difference between the sisters being caught by Catherine Darwin, who had observed them at a ball in 1826: 'Fanny Owen has quite the preference to Sarah among all the gentlemen, as she must have every where; there is something so very engaging and delightful about her.-' In the letter accompanying his book in 1872, Darwin had asked Sarah for news of the family; in reply he learned that Fanny was living in London, having been widowed six months earlier. Although Sarah visited Darwin in Down in 1874, their connection lapsed until late 1880, when they met while the Darwins were staying in London. Sarah was delighted to see Darwin again, one of her 'oldest remaining friends' and 'so happily associated with the palmy days of yore'. On this same visit, Darwin obtained Fanny's address. 'I had hoped to call & see whether Mrs. Biddulph would admit me,' he told Sarah, 'but a Russian naturalist came to luncheon & dinned me half to death & then an American naturalist, & I was half dead.' Although Darwin said that he would try again the next time he was in London, the moment had passed, and Fanny, like her letters, was destined to remain forever young in his memory.

On re-establishing contact with Sarah again in 1872, Darwin had summed up his life for her:

Despite concerns about health, the deaths of three children, and religious differences, it appears that Darwin did live happily ever after with Emma.

![Part of letter from Fanny Owen, [late January 1828] (DAR 204: 43) Part of letter from Fanny Owen, [late January 1828] (DAR 204: 43)](/sites/default/files/20200929_145807cm.jpg)