I suppose "natural selection" was bad term but to change it now, I think, would make confusion worse confounded

(Charles Darwin to Charles Lyell 6 June [1860])

Darwin encountered problems with the term 'natural selection' even before Origin appeared. Everyone from the Harvard botanist Asa Gray to his own publisher came up with objections. Broadly these divided into concerns either that its meaning simply wasn't obvious, or more seriously, that it implied agency - that something or someone was making the selection - precisely the implication Darwin was trying to avoid. By the time he was confronted with these concerns however, the term was so embedded in Darwin's own thinking that he chose to stick with it, a decision he sometimes later regretted. Debates about how easy it was to understand - or misunderstand - and suggestions of replacements, run through his correspondence over many years.

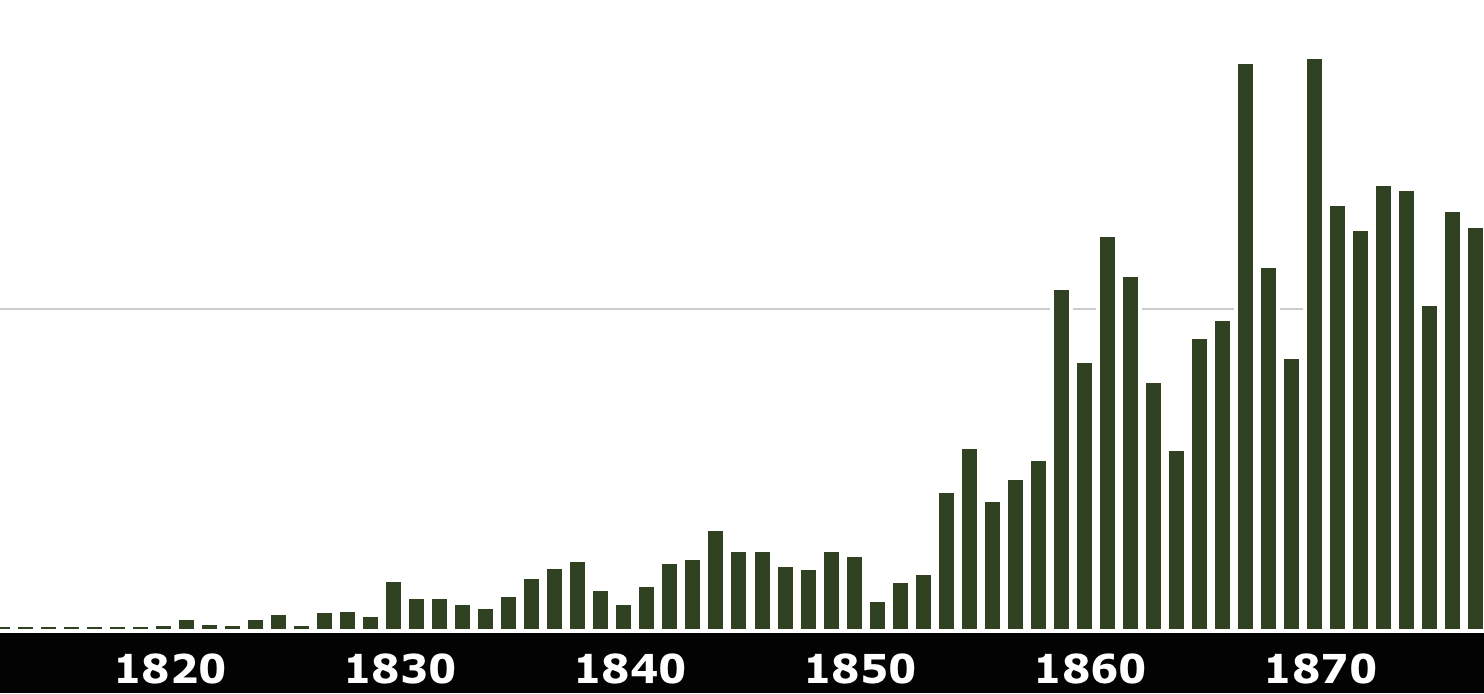

Much of the data that Darwin gathered to support the idea of species change between arriving back in England after the Beagle voyage and the publication of Origin, came from those, like pigeon fanciers, cattle farmers, and racehorse owners, who used selective breeding to enhance desirable traits in their animals. As he explained over and over again, it was by analogy with this practice of artificial selection that Darwin chose to name the adaptive process that he had identified, 'natural selection'. He used it as a section heading in the earliest outline of his theory written in 1842, and, as he told Asa Gray in September 1857, he intended to call the 'big book' he was then writing, the book where he was pulling together the research of twenty years, Natural Selection.

With that letter to Gray, Darwin enclosed a brilliantly succinct outline of his theory on the 'means by which nature makes her species', taking as his starting point the universally familiar - as he believed - role of the domestic animal breeder: 'It is wonderful what the principle of Selection by Man, that is the picking out of individuals with any desired quality, and breeding from them, and again picking out, can do. Even Breeders have been astonished at their own results. . . . I think it can be shown that there is such an unerring power at work, or Natural Selection . . . which selects exclusively for the good of each organic being'.

It was Gray's now missing response to that exposition that first alerted Darwin to one of the pitfalls he faced: 'I had not thought of your objection of my using the term "natural Selection" as an agent' he wrote back, but he was not fully convinced of the problem, protesting that he was using it 'much as a geologist does the word Denudation'. But some sort of shorthand was needed: 'I must use it,' he continued 'otherwise I shd. incessantly have to expand it into some such (here miserably expressed) formula as the following, "the tendency to the preservation (owing to the severe struggle for life to which all organic beings at some time or generation are exposed) of any the slightest variation in any part, which is of the slightest use or favourable to the life of the individual which has thus varied; together with the tendency to its inheritance"'.

It was the draft of this enclosure to Gray, along with extracts from Darwin's 1844 species essay, that was read to the Linnean Society on 1 July 1858 in the first public statement of Darwin's views. It formed part of the joint contribution with Alfred Russel Wallace: 'On the tendency of species to form varieties; and on the perpetuation of varieties and species by natural means of selection' (Darwin and Wallace 1858).

Overtaken by events, the 'big book' as originally conceived was never published, but parts were repurposed not just for Origin, but for several other publications. Darwin enshrined its working title in the proposed title of Origin: An abstract of an Essay on the Origin of Species and Varieties Through Natural Selection, but was taken aback to realise that it wasn't as self-explanatory as he had expected. 'I am, also, sorry' Darwin wrote to Charles Lyell, who had approached the prospective publisher, John Murray, on his behalf, 'about term "Natural Selection", but I hope to retain it with Explanation. . . Why I like term is that it is constantly used in all works on Breeding, & I am surprised that it is not familiar to Murray'. But he was beginning to accept that his own long study of such works meant he had 'ceased to be a competent judge.' The full title as published was: On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. ('Races' simply meant varieties or species of any organism.)

Foreign language translations brought an extra layer of anxiety. To Heinrich Georg Bronn, working on a German translation of Origin, Darwin explained his thinking once again: 'Man has altered & thus improved the English Race Horse by selecting successive fleeter individuals; & I believe owing to the struggle for existence that similar slight variations in a Wild Horse if advantageous to it would be selected or preserved by nature; Hence Natural Selection-' and encouraged Bronn to find a similar term used by German animal breeders. And in the second French edition, and at Darwin's insistence, 'sélection', a term already in use by animal breeders, was substituted for 'élection' as used in the first edition, so that 'élection naturelle' - which he really did think implied deliberate choice - became 'sélection naturelle'.

Although 'Several scientific men', as he told Bronn, had 'thought the term "Natural Selection" good, because its meaning is not obvious & each man could not put on it his own interpretation, & because it at once connects variation under domestication & nature', other readers reinforced Gray's original criticism that 'natural selection' appeared to imply a positive act of selection, if not actually a selector. Henry Holland thought the term needed closer definition: 'From different passages in the volume,' he complained, 'it might be variously interpreted, as a necessity, as an accident, as an instinct, as intellectual volition.' And suggested that Darwin alter 'some of the phrases which create ambiguity, such as "picking out with unerring skill" "working for the good of each being" "natural selection having taken advantage of" "for the sake of eliminating &c &c'.

I must be a very bad explainer.

(Charles Darwin to Charles Lyell, 6 June [1860])

To Lyell, Darwin wrote: 'I doubt whether I use term Natural Selection more as a Person, than writers use Attraction of Gravity as governing the movement of Planets &c.' but he was fighting a losing battle and conceded that he could perhaps have 'avoided the ambiguity'. A few months later he lamented that 'Several Reviews, & several letters have shown me too clearly how little I am understood'. 'I suppose "natural selection" was bad term' he admitted, 'but to change it now, I think, would make confusion worse confounded'. And then there was the problem of what he would change it to: one correspondent suggested 'Natural Evolution'; Darwin toyed with 'Natural preservation', but that 'would not imply a preservation of particular varieties & would seem a truism; & would not bring man's & nature's selection under one point of view'. 'I can only hope', he went on 'by reiterated explanations finally to make matter clearer'. Nevertheless, regret lingered, and he wrote in a later letter to Lyell: 'Talking of "Natural Selection", if I had to commence de novo, I would have used natural preservation'. (There is now a hole in the letter where Darwin wrote 'natural preservation': Lyell couldn't read Darwin's writing - his best guess was 'natural persecution'! - so cut out the words and sent them back for clarification. The editors of Darwin's correspondence have often wished they could do the same.)

By the time of the third English edition of Origin, Darwin was impelled to include a paragraph defending the term 'natural selection' against criticisms on various grounds, including its implication of conscious choice:

Several writers have misapprehended or objected to the term Natural Selection. Some have even imagined that natural selection induces variability, whereas it implies only the preservation of such variations as occur and are beneficial to the being under its conditions of life. No one objects to agriculturists speaking of the potent effects of man's selection; and in this case the individual differences given by nature, which man for some object selects, must of necessity first occur. Others have objected that the term selection implies conscious choice in the animals which become modified; and it has even been urged that as plants have no volition, natural selection is not applicable to them!

-a reference to John Edward Gray, who Darwin exclaimed understood Origin 'no more than a pig does'.

In the literal sense of the word, no doubt, natural selection is a misnomer; but who ever objected to chemists speaking of the elective affinities of the various elements?-and yet an acid cannot strictly be said to elect the base with which it will in preference combine. It has been said that I speak of natural selection as an active power or Deity; but who objects to an author speaking of the attraction of gravity as ruling the movements of the planets? . . . I mean by Nature, only the aggregate action and product of many natural laws, and by laws the sequence of events as ascertained by us. With a little familiarity such superficial objections will be forgotten.

(Origin 3d ed., pp. 84-5).

Continued in 'Survival of the fittest: the trouble with terminology Part II'