The Life of Erasmus Darwin (1879) was a curious departure for Darwin. It was intended as a biographical note to accompany an essay on Erasmus's scientific work by the German writer Ernst Krause. But Darwin became immersed in his grandfather's life, and the notice swelled to 128 pages, substantially longer than Krause's essay. Such life-writing was unusual for Darwin, but not unprecedented. Just a few years before, he had composed an autobiographical memoir for his children, and he approached the Life with a similar emphasis on the formation of his grandfather's mind and character. To compose the work, Darwin gathered materials and memories from his large extended family. The book generated a remarkably large number of letters, around 400 over a three year period. Its reception was surprisingly mixed, owing to one particular reader, Samuel Butler, who turned the book into grist for controversy.

In February 1879, Darwin received an unusual birthday present: a special issue of the German journal Kosmos produced in his honour. The issue contained an essay by Ernst Krause on the evolutionary ideas of Darwin's grandfather. Darwin was familiar with Erasmus's views on generation and development, which had been cast into verse in the epic poems, The Botanic Garden and Temple of Nature. But Darwin had never known his grandfather, who died in 1802, and he was barely mentioned in Darwin's autobiographical 'Reflections'. After reading Krause's essay, Darwin's brother Erasmus Alvey Darwin suggested that it be translated and published in English, 'for all who are interested in Darwinismus'; 'It piles up the glory and would please Francis'. Darwin's cousin, Francis Galton, had taken a keen interest in the family history as part of his larger work on hereditary genius and the comparative influence of 'nature' and 'nurture' among 'men of science'. The biographical sketch was thus a way for Darwin to trace his own intellectual ancestry and the roots of his passion for science. The piece also became a platform for commemorating his grandfather's many achievements and for rehabilitating his character. Once a celebrated poet and philosopher, Erasmus Darwin's fame had declined sharply after his death, and his reputation had been tarnished by several biographies.

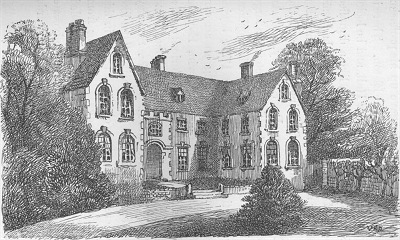

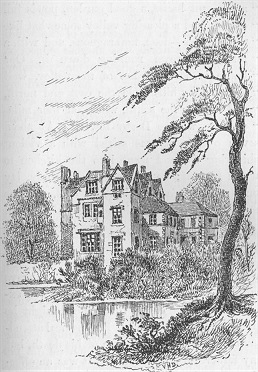

'I am myself wholly & shamefully ignorant of my grandfathers life', Darwin wrote to Krause on 14 March 1879. He made contact with family members, some of whom he had not seen or heard from in decades. 'It is indeed long since we met', wrote Reginald Darwin, his father's half-brother. 'Never but once since your return from your five years voyage ... your name however is so completely before the world that I seem to hear of you constantly, & always with pride-'. Reginald had some of Erasmus's possessions, including a commonplace book, which proved to be a storehouse of private thoughts and experiences. Reading it, Darwin said, was like 'having communication with the dead'. At Down House, Darwin discovered a cache of letters in a box marked 'old deeds': 'The more I read of Dr. D. the higher he rises in my estimation'. Violetta Darwin, a distant cousin and book illustrator with an interest in historic buildings, made drawings of the homes where Erasmus had lived. Her sketches of Elston Hall where he was born, and Breadsall Priory where he resided at his death, both appeared in Darwin's Life.

'It is remarkable', wrote Violetta, 'how the word "benevolent" has always been associated with Dr. Darwin by his friends'. She recalled an anecdote of the doctor rescuing a drunken man from a ditch, whom he brought back to his home to care for overnight, only to discover that it was his brother-in-law. More colourful tales were exchanged in letters. Another cousin, Elizabeth Wheler, told the story of a visit to Newmarket during the horse racing season. 'In the middle of the night he heard his door open softly, & a man entered, came to his bedside & made him a sign to be silent. He then said "Dr. Darwin I am the Jockey who is to ride the favourite Horse tomorrow, & upon whom large bets are laid, you once saved my wife's life when very ill with a fever, & I can now shew you my gratitude, make any bets you please against the favourite Horse, for we Jockies have settled he shall not win. My gdfather thanked the man & requested him to leave the room. He continued his journey to Margate the next day, & on his return thro' Newmarket he asked which Horse had won, & was told that, to the surprise of everyone, the Horse that was thought sure to win, & on whom thousands had been bet, had failed just at the last, & come in third or fourth'.

Darwin tried to verify such tales passed down in the family over two or three generations, comparing the accounts from different relatives. He asked Reginald to confirm the doctor's run-in with a high-way robber. 'The Miss Galtons say that he visited the man in prison and heard why he did not rob our grandfather. Mrs. Nixon seems to know nothing of this latter part of story, and thinks that our grandfather only suspected that the man intended to rob him'. Again, the story was told most vividly by Elizabeth Wheler: 'Dr. D. was riding on a lonely road to Nottingham to see a Patient late in the Even.g. A suspicious looking man rode past him, & then went slowly for Dr. D to pass him. This happened once or twice. At last Dr. D said "A fine Even.g Sir" or something of that sort. The man made a short reply & rode away. The next day a man was taken up on that very spot for robbing some Traveller. Dr. D. had the curiosity to go to the prison & found it was the very man who had passed him the day before. & on asking why he had not robbed him the man replied "I had intended to do so, but thought it was you, & when you spoke I was sure. you saved my life many years ago, & nothing would induce me to rob you"'. The story of jockey and the robber were both included in the Life, pp. 63-5.

One of Darwin's aims in assembling these episodes was to illustrate his grandfather's good will and strength of character, which had been tarnished by previous biographies. Many of Darwin's relations had expressed their disgust for the Memoirs of the life of Dr Darwin by Anna Seward, once a companion and fellow-poet of Erasmus. 'At the time Miss Sewards life of Dr. Darwin came out', wrote Emma Galton, 'the family were so angry with the false accounts put in, that my mother says, Dr. Robert Darwin (of Shrewsbury) obliged her to contradict many things she had written, in the Reviews of the day- Those reviews are forgotten, & her book remains'. Contempt was also poured on the memoir by Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck, one of Erasmus's nieces, whose family had evidently quarrelled with the doctor. 'She had the habit of coloring her facts till they almost ceased to be true', wrote Elizabeth Wheler. 'My Mother always spoke of her Father with the utmost reverence & affection, his refined & agreeable manner & his kindness to his children. He had no teeth in his head, & was very fond of milk & any thing made of milk cream cheese & such like, but I am sure my Mother would have been shocked at Mrs. Schimmelpenigs account of his greediness'.

While Darwin was writing his lengthy notice, Krause revised and greatly enlarged his Kosmos essay. One of Krause's aims was to address the recent book by Samuel Butler, Evolution Old and New, which discussed Erasmus Darwin's ideas alongside those of Lamarck, Buffon, and Darwin's Origin of Species. Butler had once been an enthusiastic supporter of Darwin, but he had grown critical of natural selection and the apparent lack of purpose and direction that such a theory implied. He also came to regard 'Darwinism' and 'Darwinists' as a new form of scientific elite and doctrinal authority, akin to the church and its clergy. He found inspiration in earlier developmental theories, and in some of Darwin's harsh critics, especially St. George Mivart. Darwin had struggled to understand Butler's Life and Habit (1878), which seemed to attribute memory to organic matter: 'Even if we grant memory & the power of wishing to cells, & this is an enormous admission, I do not see how cells are to modify themselves chemically & structurally either by wishing or remembering'. 'He is a very clever man,' he wrote to Krause, but 'knows nothing about science & turns everything into ridicule. He hates scientific men'. Krause wanted to correct and refute Butler's 'immeasurably superficial and inaccurate piece of work', but Darwin advised him not to 'expend much powder & shot on Mr Butler'.

The final text of the Life was a product of substantial revision. Krause's essay was considerably altered and shortened. The final version did not mention Butler's work directly, but it did allude to it unfavourably in the final sentence: 'Erasmus Darwin's system was in itself a most significant first step in the path of knowledge which his grandson has opened up for us, but to wish to revive it at the present day, as has actually been seriously attempted, shows a weakness of thought and a mental anachronism which no one can envy' (Life, p. 216). Darwin's biographical sketch was shortened and re-arranged, mostly on the advice of his eldest daughter. 'Henrietta thinks my notice of Dr. D very dull, - almost too dull to publish, & I believe that she is right... No one will ever catch me again trying to go beyond my tether'.

The book was published in November of 1879. Darwin filled his notice with lengthy extracts of letters and poems, and testimony on his grandfather's many virtues: freedom from vanity, charity to the poor, kindness to servants, temperance and moderation in habits and temperament. He dismissed Seward's slanders as pure fictions, motivated by her desire for attention and revenge, and her disappointed affection. He described some of his mechanical inventions and innovations in chemistry, agriculture, and medical theory; and hinted at the inherited attributes for poetry, powers of observation, and sympathy. No mention was made of his ideas on the origin, development and modification of life, perhaps because these were discussed in detail by Krause. But a similar reticence about his grandfather's evolutionary thought had characterized Darwin's historical sketch to Origin of Species, which had just one brief note on the 'curious' anticipation of the 'views and erroneous grounds of opinion' of Lamarck.

The Life was very well received by the family, all of whom agreed that the book vindicated Erasmus's character and restored his good reputation. Francis Galton was pleased to have been mentioned among the distinguished descendants of Dr. Darwin, and found support for his own views on hereditary genius: 'The biography seems to me quite a new order of writing, so scientifically accurate in its treatment... I see you have mentioned me twice, very kindly-but too flatteringly for my deserts... the "visualising" faculty of Dr. Darwin appears to have been remarkable & of a peculiar order & it is possible that your's through inheritance may also be similarly peculiar'. Reviews were generally positive, but the reception of the book was soon coloured by a peculiar controversy.

Butler, whose Evolution Old and New had been published in May of 1879, had not failed to find the allusion to his own work in the final sentence of Krause's essay. He seized upon an inconsistency in the preface, where Darwin stated that Krause's piece had been written before Evolution Old and New was published. On reading Krause's original Kosmos article, Butler found that the essay had been substantially changed, and he wrote to Darwin for an explanation: 'Among the passages introduced are the last six pages of the English article, which seem to condemn by anticipation the position I have taken as regards Dr Erasmus Darwin in my book Evolution old & New, and which I believe I was the first to take'. Darwin tried to resolve the matter in private, explaining that such revision was 'common practice', and offering an apology: 'it never occurred to me to state that the article had been modified; but now I much regret that I did not do so'. On the top of Butler's letter, Emma Darwin wrote: 'it means war we think'.

Indeed, Butler was unsatisfied with Darwin's reply, and 'decided on laying the matter before the public'. He stated his case in a letter to the Athenaeum, a leading literary weekly. He accused Darwin of purposely misleading his readers, and implied that the whole book had been written as an attack on himself: 'It is doubtless a common practice for writers to take an opportunity of revising their works, but it is not common when a covert condemnation of an opponent has been interpolated into a revised edition, the revision of which has been concealed, to declare with every circumstance of distinctness that the condemnation was written prior to the book which might appear to have called it forth, and thus lead readers to suppose that it must be an unbiased opinion'. Darwin was extremely vexed by the accusations and uncertain about what to do. He wrote two drafts to the Athenaeum, but was urged by most of his family and friends to ignore the matter. 'The world will only know or at any rate remember that you & Butler had a controversy in which he will have the last word-' advised Henrietta; 'not one reader in a thousand will make head or tail of the grievance....', added her husband Richard.

Despite Darwin's refusal to engage, the controversy lingered on. Butler stirred the pot with his next book Unconscious Memory (1880), devoting several entire chapters to the affair, and elevating the charges against Darwin to wilful deceit. Again Darwin felt compelled to reply, and family members rallied round and debated the best course of action. His son Leonard suggested inserting a flysheet into unsold copies of the Life. Krause wrote a detailed defense, and George Romanes published a scathing review in Nature, all of which confirmed Butler's belief in the conspiracy of Darwinists. With Henrietta's aid, the advice of a leading journalist, Leslie Stephen, was consulted. Darwin apologised for the intrusion, but explained: 'it is difficult to avoid being pained at being publicly called in ones old age a liar'. Stephen's reply was unhesitating: 'take no further notice of Mr Butler whatever'.

Brief notice was taken, however, some years later. The Life of Erasmus Darwin was not reprinted in Darwin's lifetime, but a second edition appeared in 1887, with the following note: 'Mr. Darwin accidentally omitted to mention that Dr. Krause revised, and made certain additions to, his Essay before it was translated. Among these additions is an allusion to Mr. Butler's book, 'Evolution, Old and New.' From beyond the grave, it seems, Darwin had the last word.