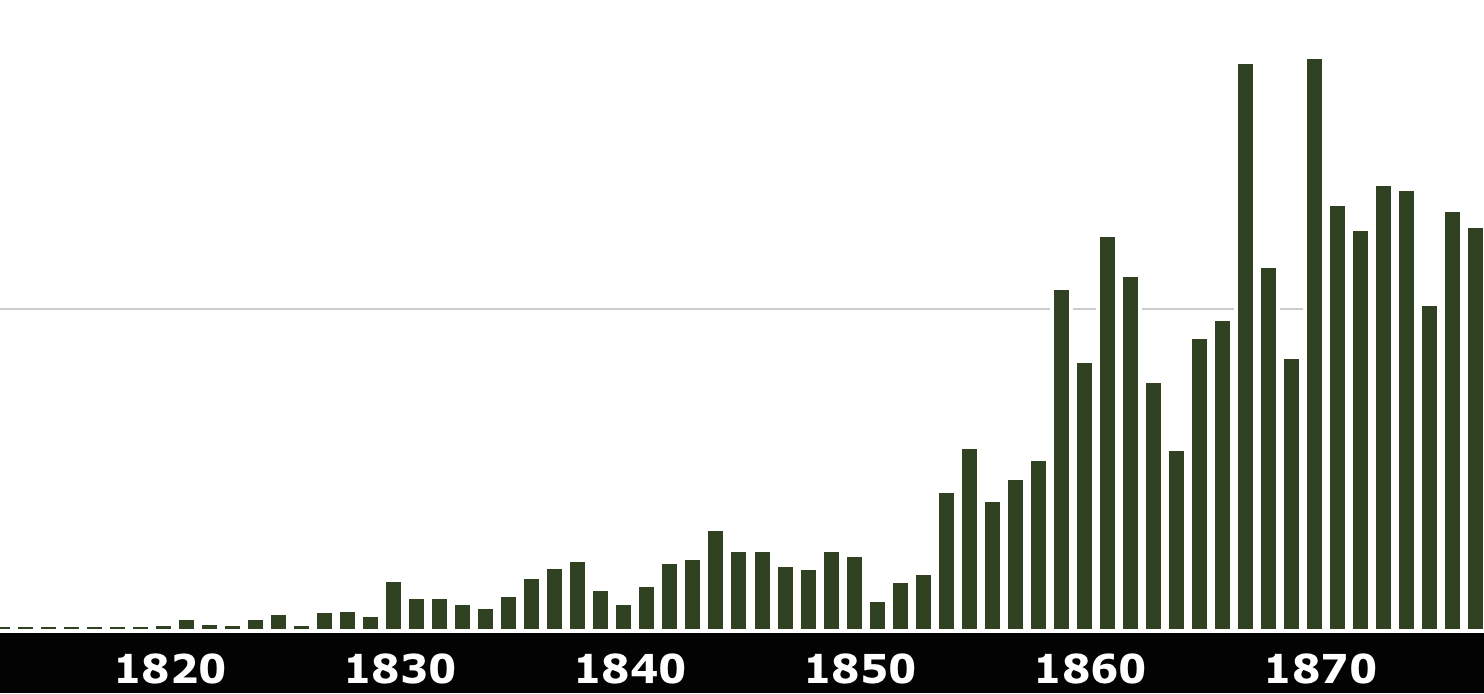

Towards the end of 1862, Darwin resolved to build a small hothouse at Down House, for 'experimental purposes' (see Correspondence vol. 10, letter to J. D. Hooker, 24 December [1862], and volume 10, letter to Thomas Rivers, 15 January 1863). The decision was evidently prompted by his growing engagement in botanical experimentation, and the building of the hothouse early in 1863 marked something of a milestone in Darwin's botanical work, since it greatly increased the range of plants that he could keep for scientific investigations. Of course, Darwin had been engaged in botanical experiments over many years, and there had been a greenhouse, evidently built at least in part for his botanical work, at Down House since the winter of 1855-6 (see CD's Classed account book (Down House MS) and Correspondence vol. 5, letter to J. D. Hooker, 19 April [1855]). Darwin became increasingly involved in botanical experiments in the years after the publication of Origin, and made more frequent references in correspondence to his use of the greenhouse for experiments (see Correspondence vols. 8-10). Though his greenhouse was probably heated to some extent, Darwin found himself on several occasions in need of what he called a 'hothouse', meaning a construction suitable for tropical plants. In 1861 and 1862, while preparing Orchids, he was allowed 'free use' of the hothouses and some of the tropical plants of his friend and neighbour George Henry Turnbull, and he relied again on Turnbull's hothouses in his experiments, begun in 1861, on the Melastomataceae, a family of tropical and sub-tropical plants (see Orchids, p. 158 n., and Correspondence vols. 9 and 10). However, he found it increasingly necessary to ask the botanists at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and private individuals with collections of hothouse plants to make observations and even experiments on his behalf.

Darwin's decision to build a hothouse was thus obviously prompted by his increasing use of plants for a variety of experimental purposes. The particular spur seems to have been his desire to grow the tropical plant Oxalis sensitiva, in order to investigate the effects of various substances on its sensitivity to touch (see Correspondence vol. 10, letter to J. D. Hooker, 12 [December 1862] and n. 13). Initially, Darwin purchased for this purpose a glass plant-case, heated by means of a dish that had to be filled with hot water twice daily. However, either because he found this to be unsatisfactory, or because he simply decided to work on a larger scale, he soon determined to build a hothouse as well. He was persuaded to do so by John Horwood, the gardener of his neighbour George Turnbull; Horwood had assisted him in the use of his employer's hothouses over the previous two years. In a letter of 24 December [1862] (Correspondence vol. 10) Darwin told Hooker:

I have almost resolved to build a small hot-house: my neighbours really first-rate gardener has suggested it & offered to make me plans & see that it is well done, & he is a really a clever fellow, who wins lots of prizes & is very observant. He believes that we shd succeed with a little patience; it will be grand amusement for me to experiment with plants.-

According to John Claudius Loudon's Encyclopedia of gardening (Loudon 1835), a copy of which Darwin signed in 1841 (see the copy in the Darwin Library-CUL), the word 'hothouse' had two meanings. It was applied generally to all forms of protected plant accommodation, including frames, glass cases, greenhouses, orangeries, conservatories, dry-stoves, and moist- or bark-stoves (p. 1012). More particularly, it was synonymous with 'bark-stove', a construction designed to house those plants that required 'the highest degree of heat' (p. 1100). The latter was the sense in which Darwin used the word.

The building of the hothouse was begun in mid-January, and completed by mid-February (see letters to J. D. Hooker, 13 January [1863] and 15 February [1863]). It was built by William Ledger, a builder from the nearby village of Hayes, and cost a total of £85 11s. 1d.; this included £22 5s. for Horwood, who superintended the operation, and £9 15s. 10d. for fittings purchased in July (see CD's Classed account book and his Account book-cash accounts (Down House MS)). When it was completed, Darwin told Turnbull that without Horwood's aid he would 'never have had spirit to undertake it', and that, if he had had, he would 'probably have made a mess of it' (letter to G. H. Turnbull, [16? February 1863]).

Even before work on the hothouse started, however, Darwin began making preparations to stock it with plants for use in a wide variety of experiments. He told Hooker that he was 'looking with much pleasure at catalogues to see what plants to get', adding 'I shall keep to curious & experimental plants' (letter to J. D. Hooker, 13 January [1863]). Darwin apparently refers to the catalogues of a local nurseryman, John Cattell of Westerham, with whom he had dealt over many years. In his letter to Hooker, Darwin mentioned that he hoped to be able to borrow 'some few orchids' from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, dreading the 'awful sums' that he imagined they would cost to buy. Hooker's response was unequivocal: 'You will give me deadly offence if you do not send me your Catalogue of the plants you want before going to Nurserymen' (letter from J. D. Hooker, [15 January 1863]). Darwin agreed to send Hooker his list of 'experimental' plants, while observing: 'anything ornamental[,] which, however, I shall avoid[,] of course I must not have from Kew' (letter to J. D. Hooker, 30 January [1863]).

Darwin probably gave his list of plants to Hooker when he visited Kew on 11 February (see Emma Darwin's diary (DAR 242)). Four days later, the construction was completed and he was impatiently waiting to hear what plants Hooker could let him have, telling him: 'I long to stock it, just like a school-boy' (letter to J. D. Hooker, 15 February [1863]). On 20 February, the plants from Kew had arrived. Darwin was delighted, telling Hooker: 'I am fairly astounded at their number! why my hot-house is almost full!- I have not yet even looked out their names; but I can see several things which I wished for, but which I did not like to ask for' (letter to J. D. Hooker, [21 February 1863]). He had, he confessed to Hooker, 'stewed so long admiring the plants' that he developed a headache. What he did not confess to Hooker was that he had also been in a state of 'agitation' because his gardener, Henry Lettington, had potted up the temperamental and valuable tropical orchids in 'common earth'. Horwood had had to be sent for 'instanter', 'to undo them & pot them as they like' in a particular mixture of moss, peat, and charcoal (see the letter from Henrietta Emma Darwin to William Erasmus Darwin, [22 February 1863] in DAR 210.6: 109). There were other teething problems, and Hooker had to warn Darwin not to make 'boiled greens' of his plants, proffering further advice on cultivation (see letter from J. D. Hooker, [6 March 1863]).

Darwin derived enormous pleasure from his hothouse plants, telling Hooker: 'Henrietta & I go & gloat over them; but we privately confessed to each other, that if they were not our own, perhaps we shd. not see such transcendent beauty in each leaf' (letter to J. D. Hooker, 24[-5] February [1863]). Darwin's aesthetic appreciation of the tropical plants was probably partly due to the recollections they inspired of his own travels in the tropics. Even before he left on the Beagle voyage, Darwin used the hothouses in the Cambridge University botanic garden to envision the tropics (see Correspondence vol. 1, letter to Caroline Darwin, [28 April 1831]), and when, on the Beagle, he heard about the building of a hothouse at his father's house in Shrewsbury, he commented: 'how when I return I shall enjoy seeing some of my old friends again' (Correspondence vol. 1, letter to Catherine Darwin, May-June [1832]). Years later, the great hothouses at Chatsworth House, Derbyshire, made him 'thrill with delight at old recollections' of the tropics (Correspondence vol. 3, letter to Charles Lyell, 8 October [1845]).

Having indulged his senses, Darwin soon began the more serious work of listing the plants, seeking to identify the families to which they belonged. In his letter to Hooker of 5 March [1863], he announced that the plants from Kew were '165 in number!!!', continuing: 'Do you not think you ought to be sent with Mr Gower to the Police Court?' (William Hugh Gower, superintendent of the propagating department at Kew, had helped select the plants for Darwin). Hooker had also sent seeds, and was attempting to obtain others from Paris, so that Darwin felt he had to reiterate: 'All that were on list were for experiments, which seem to me really worth trial' (letter to J. D. Hooker, 21 February [1863]).

Darwin's hothouse became an important focus for his experiments. By the spring of 1864, he was thinking of expansion, telling Hooker: 'I am so magnificent that I am thinking of building a large greenhouse & turning the present green house into a cool Stove [that is, cool hothouse]' (Correspondence vol. 12, letter to J. D. Hooker, 26[-7] March 1864). The plan was quickly set in motion, and once again Darwin relied on Horwood to superintend the work, while William Ledger did the building. By August 1864, he had spent £126 10s. on the new heated greenhouse, and on iron pipes to convert the original greenhouse into a cool hothouse (Classed account book (Down House MS)). Subsequent references make clear that the new greenhouse comprised two halves kept at different temperatures, and in 1869 Darwin told the botanist William Chester Tait that he had '4 houses of different temperatures' (letter to W. C. Tait, 12 and 16 March [1869], Calendar no. 6661).

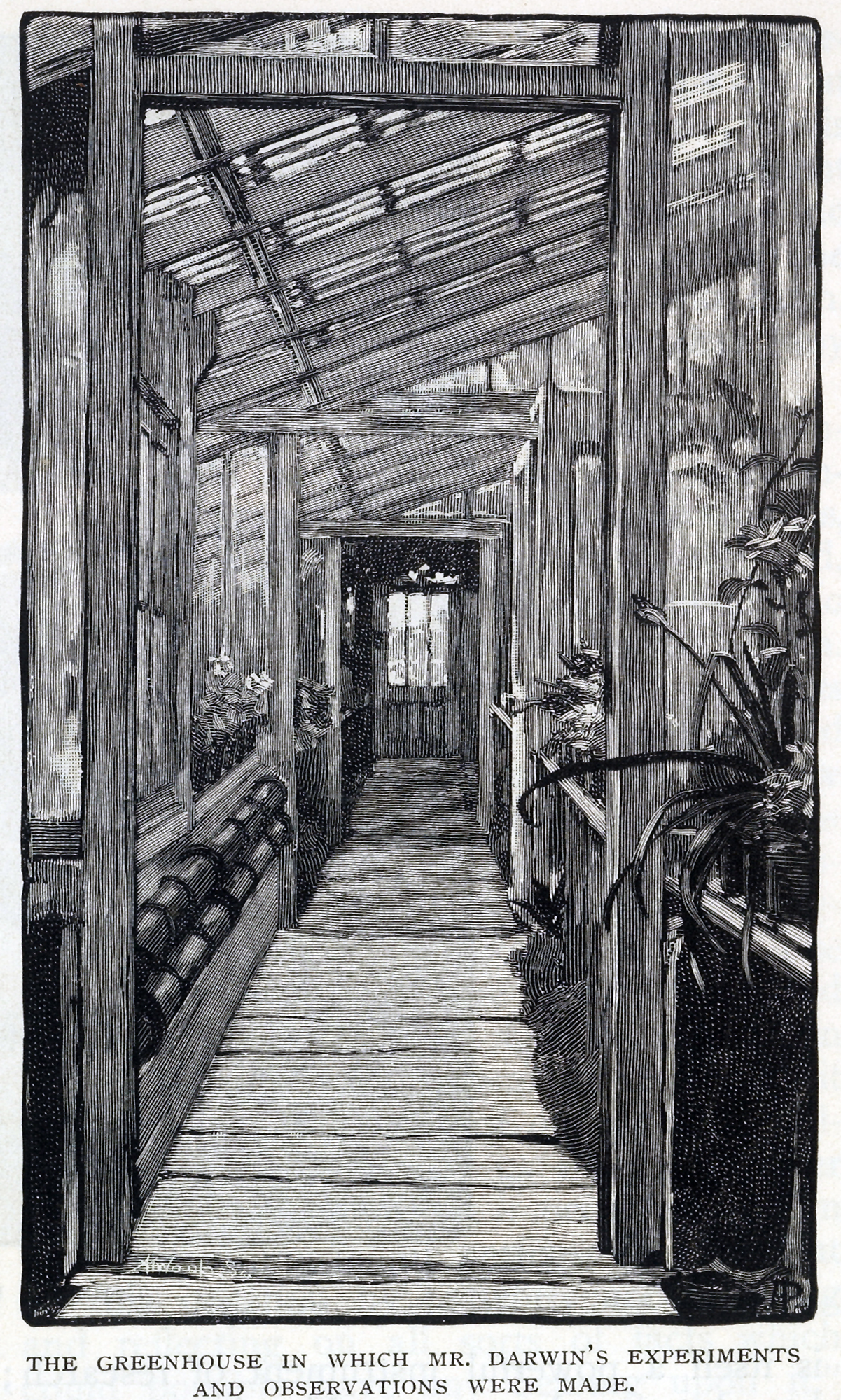

Darwin's greenhouse complex, comprising these four distinct sections, was a series of lean-to constructions, built inside the boundary wall of Darwin's long kitchen garden, at the end nearest the house (see plan, opposite). Inspection of the surviving brickwork of the original base confirms that the complex resulted from three separate building phases, although the superstructure was replaced after Darwin's death, and one section of the 1864 greenhouse was subsequently demolished. The appearance of the complex at about the time of Darwin's death, showing the four distinct sections, is represented in the illustration from the Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine for January 1883. The drawing provides an interior view, looking away from the house, apparently from within the original greenhouse (later the cool hothouse). Thus, as far as can be determined, the section in the foreground, with pipes clearly visible, is the hothouse of 1863.

Over many years, the greenhouse complex was an important site of Darwin's research, complementing his study, in which he carried out many botanical experiments (see, for example, A. de Candolle 1882, p. 495). The greenhouses were, according to Francis Darwin, the first port of call on his father's midday walk, when he would look 'at any germinating seeds or experimental plants which required a casual examination' (LL 1: 114). Even when he was ill, Darwin would make the effort to walk a distance that he thought 'must be more than 100 yards' to the greenhouses (Correspondence vol. 12, letter to J. D. Hooker, [25 January 1864]).

In view of the importance of Darwin's hothouse plants in his experimental work, it is appropriate to reproduce here two lists of hothouse plants drawn up by Darwin; these lists are in DAR 255: 8 and DAR 255: 2-5. The first is a list that Darwin apparently drew up from the catalogue of John Cattell, from whom he had bought plants for his garden over many years. Darwin's Classed account book gives an entry under 'Science', dated 28 March 1863, for five guineas' worth of plants bought from Cattell, suggesting that he bought at least some plants for the new hothouse from Cattell at this time. (Usually, purchases of plants from Cattell were listed in the account book under the heading 'Garden'.) The heading to the list suggests that it is a copy of a list drawn up for the nurseryman Hugh Low, of Clapton, London, for the purpose of obtaining comparative prices. It was certainly not the list that Darwin gave to Hooker, since Hooker 'marked out' on that list the plants he could not supply (see letter from J. D. Hooker, [16 February 1863]). However, it can be dated with some certainty to the period when the first hothouse was built by at least two details. Firstly, Darwin specifically mentioned 'Gloxinia droopy & upright' both in this list and in his letter to J. D. Hooker, 15 February [1863]. Secondly, he mentioned in this list, as an afterthought, the species Edwardsia tetraptera, citing Treviranus 1863a, which he received in mid-February (see letter from L. C. Treviranus, 12 February 1863).

The second list is headed 'Stove Plants', and itemises more than 130 species and their associated orders or families. This list is on four sheets of identical paper, bearing the watermark date 1860. This may be the list that Darwin made of the plants sent to him by Hooker (see letter to J. D. Hooker, 5 March [1863]), since many of the species listed were referred to in subsequent correspondence as having been sent to Darwin from Kew. Darwin said in the letter to Hooker of 5 March [1863] that he had received 165 plants from Kew; however, the numerical discrepancy may be accounted for in a number of ways. There may, for example, have been an additional sheet which is now missing, or Darwin's '165' may have referred to the number of individual plants rather than the number of species. Perhaps most likely is that several species were grouped under a single heading in the list, such as 'Melastomaceæ (Sin[g]apore)' or 'Catasetum species?'. However, even if the list is not that referred to by Darwin, it provides important evidence of the species that he had been anxious to obtain at this time, and as such is a useful indication of his experimental concerns.

The manuscript lists are reproduced below as closely as possible to the original format, with all alterations, interlineations, and additions noted. The symbol § denotes a tick marked in pencil. The footnotes are intended to clarify the transcription and, where possible, to provide the correct nineteenth-century spellings of the species, genera, families or orders listed. Corrected spellings are taken from Lindley 1853, Index Kewensis, the Gray Herbarium index, and Index Londinensis.

List of plants from Cattell's catalogue

Transcription:

Hugh Low & Co.1- Cattell2 will get me at prices below without carriage

| § Asclepias currasavica3 |

1.6 |

|

| -- rosea |

do |

|

| § Seed of common annual Mimosa | ||

| Canna Warscewisii-4 |

2.6 |

|

| § Gloxinia droopy & upright |

1.6-to 3.6. |

|

| Malpighia urens |

5 |

|

| Pentas rosea |

1.6 |

|

| Poinsettia pulcherrima |

3.6 |

|

| § Cyanophyllum magnificum |

7.6- 21 |

|

| -- speciosa5 |

do. do. |

|

| § Melastoma atropurpurea6 |

2.6 |

|

| -- trinerva7 |

2.6. |

|

| Maranta -- |

2.6 |

|

| Ruellia aurantiaca |

2.6 |

|

| § -- maculata |

1.6. |

|

| §Allamanda & Dipladenia |

2.6 or 3.6.

|

Get Edwardsia tetraptera mentioned by Treviranus Honey.8

| Acropera Loddigesii.- |

10.6 |

Catasetidæ | ||

| Catasetum cristatum |

do |

Clowesia | ||

| -- Russelianum9 |

do. |

Cyrtopodium. | ||

| -- | ||||

| § Gongora atropurpurea |

5 |

§ Cyrtopodium Andersonii |

10.6 |

|

| § -- maculata |

5 |

-- punctata10 |

10.6 |

|

| Mormodes auraticum11 |

21 |

|||

| Anoectochilus argenteus 12 |

5s. |

|||

| § Stanhopea grandiflora |

7.6. |

-- pictus .13 |

8 s |

|

| Neotteæ |

Disa

Vinca-like Plant

Drosera14

Sarracenia- Nepenthes

Asclepias- species

Poinsettia

Catasetidæ

Melastoma with good sized flowers- a Bush.

Cyanophyllum-

Bolbophyllum15

Cypripedium barbatum

moveable Labellum. (Bateman16)

Stilidyum adnatum.17 1.6. Low

Brugmansea-18 flowers turn up in Moonlight

Bryanthus erectus hybrid form

Menziesia cærulea empetriformis19

Rhodathamnus chæmæcistus20

Provenance: DAR 255: 8

Notes

1. Hugh Low & Co. was a firm of nurserymen, seedsmen, and florists with premises at Clapton, London (Post Office London directory 1863).

2. John Cattell was a florist, nurseryman and seedsman with premises at Westerham, Kent (Post Office directory of the six home counties 1862).

3. Asclepias curassavica.

4. Canna Warszewiczii.

5. 'speciosa' deleted in pencil.

6. This name has not been found in botanical reference works.

7. Melastoma trinerve or M. trinervium.

8. This sentence added in pencil. The reference is to Ludolph Christian Treviranus and to Treviranus 1863a, p. 10. See also letter to J. D. Hooker, 24[-5] February [1863] and n. 19.

9. Catasetum Russellianum.

10. '-- punctata' deleted in pencil. CD misspelled Cyrtopodium punctatum.

11. Mormodes aurantiaca

12. 'Anoectochilus argenteus 5s.' deleted in ink.

13. '-- pictus 8 s.' deleted in ink.

14. 'Drosera' added in pencil.

15. Bulbophyllum.

16. The reference is to James Bateman, an orchid specialist (R. Desmond 1994).

17. Stylidium adnatum.

18. Brugmansia.

19. 'cærulea' deleted in pencil, 'empetriformis' added in pencil.

20. Rhodothamnus chamaecistus.

List of 'Stove Plants'

Transcription:

Stove Plants

| 'Cordilyne heliconæfolia1 | Asphodeleæ | |

| Marcgravia umbellata | Marcgraviaceæ. Guttiferæ | |

| Aristolochia Thwaitesii | ||

| Rivinia humuli2 | Phytolacceæ3 | |

| Artanthe mollicoma | Piperaceæ | |

| Myroxylon cleriesii4 | Flacourtaceæ5- Violales | |

| Passiflora punctata | ||

| P. Hartwissiana6 | ||

| - cærulea racemosa | ||

| - hybrida floribunda | ||

| Chirita Walkerii7 | Cyrtandraceæ- | |

|

Gesneraceæ |

||

| Lopezia axilare8 | Onagreæ9 | |

| Leea coccinea | Amelidæ10- Santalaceæ | |

| Alloplectis chrysanthum11 | Gesneraceæ | |

| Saccharum officinarum | Gramineæ | |

| Acropera luteola | Orchids | |

| -- Loddigesii | ||

| Gongora maculata | ||

| Catasetum purum | ||

| Bolbophyllum barbigerum12 major | ||

| -- careyanum13 | ||

| Angræcum eburneum | ||

| Cyrtopodium punctatum | ||

| Coffea Bengalensis | Cinchonaceæ | |

| Nepenthes distillatoria | ||

| Desmodium gyrans | Leguminosæ | |

| Oxalis sensitiva: O Braziliensis14 | ||

| O. crenata. O Bowii.15O. cluphurifolia16 | ||

| Caladium Houlletii: Chemtini:17 | Aroidæ18 | |

| verschaffeltii | ||

| C. hæmatostigma. | ||

| Gloriosa Leopoldi19 | ||

| Gloxinia atro-violacea20- Laura erect bits21 | ||

| Carthusiana22 | ||

| Costus Malortianus23 | Scitamineæ | |

| Lasiandra Fontanesiana | Melastomaceæ | |

| Noryska Chinensis24 | Hypericineæ | |

| Ixora coccinea | Rubiaceæ | |

| -- Javania25 | " | |

| Stemonacanthus macrophyllus | Acanthaceæ | |

| Capparis ferruginei26 | Capparidæ27 | |

| Sericographis squarrosa | Acanthaceæ | |

| Hamelia patens | Rubiaceæ | |

| Eucharis grandiflora | Ameryllidæ28 | |

| Urostigma rubiginosum | Figs | |

| Cyanophyllum magnificum |

M r Low29| of |

Melastomaceæ |

| Daphne Indica rubra odorata |

Clapton |

|

| Ruellia maculata | Acanthaceæ | |

| Dipladenia micro? Urophylla30 | Apocyneæ | |

| Brugmansia arborea | ||

| Nepenthes ampullacea | ||

| Sarracenia viriolaris31 | ||

| Catasetum species? | ||

| Gongora ? | ||

| Cyrtopodium ? | ||

| Stanhopea ? | ||

| Jasminium pauciflorum32 | ||

| Meyenia erecta | Solanaceæ Cestrineæ | |

| Abutilon Duc de Melekoff | =Sida Malvaceæ | |

| Higgensia argyroneurra33 | Cinchonaceæ | |

| -- pyrophylla34 | " | |

| -- discolor35 | ||

| Columnea scandens | Scrophulariæ- S. America | |

| -- Schiedeana | " | |

| Freycinettia imbricata36 | Bromeliaceæ | |

| Ficus barbata | ||

| Tecoma undulata | Bignoniaceæ- Personatæ | |

| -- capensis | ||

| Phyllarthron comorense | Jus. Masc.37 Bignoniaceæ | |

| Plumbago capensis | ||

| Franciscea latifolia | Brazil - Rhinantheæ38 | |

| Scrophulariaceæ | ||

| Pandanus graminifolius | ||

| Cyphomandra betacea | Solanaceæ | |

| Cryptostegia grandiflora | Asclepiadæ39 Ind. Or.40 | |

| Bexia Madgascariensis41 | Aquifoliaceæ | |

| Thryallis brachystachys42 | Malpighiaceæ Brazil | |

| Gardenia florida | Gardeniaceæ or Rubiaceæ | |

| Ind. Or. China | ||

| Bougainvillea speciosa43 | Nyctagineæ | |

| Torenia pucherrima44 | Scrophulariaceæ | |

| Hoya carnosa | Asclepiadæ45 | |

| Clusia incarnata46 | Guttiferæ | |

| Dipeteracanthus Herbstii47 | =Ruellia Acanthaceæ | |

| Allamanda Schotti48 | Apocyneæ | |

| -- nerifolia49 | ||

| Pentas carnea | Rubiaceæ | |

| Chrysophyllum albidum | Sapoteæ50 | |

| Aristolochia gigas | ||

| Lagerstroemia regina51 | Lythraceæ | |

| c Malabar | ||

| -- indica | ||

| Pleroma heteromalla52 | Lythorariæ-53 | |

| Melastomaceæ | ||

| Justicea carnea54 splendens55 | Scophuseriaceæ56 | |

| " " diclyptera57 speciosa | ||

| " " hyssopifolia | ||

| Roxburgia58 | Aroidæ59 Ind. Or. | |

| Dieffenbachia seguine picta | = Caladium | |

| Pogostemon patchouli60 | Labiatæ | |

| Xylophylla speciosa | Euphorbiaceæ -Rutaceæ | |

| Euphorb. Jamaica | ||

| Pointsettia pucherrima61 | do | |

| Dracæna terminalis | Asphodeleæ | |

| Vivipara62 | ||

| -- fragrans | ||

| Sphærostema marmorata63 | Schizandraceæ- near | |

| Menispermales | ||

| Chiococca racemosa | Rubiaceæ Ind. Occ.64 | |

| Stylidium graminifolia65 | Campanulaceæ- Stylideæ | |

| Ficus aspra66 | ||

| Clidemia crenata | = Melastoma Brazil | |

| Adhadota cydonifolia67 | Acanthaceæ,- Justiceæ68 | |

| Vinca rosa69 | alba Apocyneæ | |

| Stephanotis floribunda | = Ceropegia- Apocyneæ- | |

|

Asclepiadæ70 |

||

| Cyrtandra Dohliana71 | Scrophulariæ | |

| Melastomaceæ (Sinapore)72 | ||

| Vinca rosea alba | Apocyneæ | |

| Plumbago zeylarnica73 | Plumbagineæ | |

| Sonerilla margaritacea74 | Lythraceæ or Melastomaceæ | |

| Scutellaria trianea75 | Labiatæ | |

| Anthurium cartilagineum | Aroidæ76 = Pothos | |

| -- podophyllum | ||

| -- cardifolium77 | ||

| Ceropegia gardnerii78 | Apocyneæ- Asclepiadæ79 | |

| Croton longifolium80 | Euphorbiæ | |

| -- variegata81 | ||

| Aschynanthus lianus82 | Bignoniaceæ | |

| -- Teysmanianus83 minialis84 | ||

| Clavija undulata | Myrsineæ. S. Am. | |

| Euphorbia lophogona | ||

| Malpighia punicifolia | Malpighiaceæ | |

| -- aquifolia | ||

| Arduina grandiflora | Apocyneæ | |

| Melastoma macrocarpa85 | Melastomaceæ | |

| Cissus discolor | Viniferæ | |

| Andropogon podophyllum86 | Gramineæ | |

| Elaeis guiniensis87 | Palmæ | |

| Coelibogyne ilicifolia88 | Euphorbiæ | |

| Impatiens Hookeriana | Balsamineæ |

Provenance: DAR 255: 2-5

Notes

1. Cordyline heliconiaefolia.

2. Rivina humilis

3. 'Phytolacceæ' preceded by 'o' added in pencil.

4. This name has not been found in botanical reference works.

5. Flacourtiaceae.

6. Passiflora Hartwiesiana.

7. Chirita Walkeri.

8. Lopezia axillaris.

9. Onagrae.

10. Ampelidae.

11. Alloplectus chrysanthus.

12. Bulbophyllum barbigerum.

13. Bulbophyllum Careyanum.

14. Oxalis brasiliensis.

15. Oxalis Bowiei.

16. Oxalis bupleurifolia.

17. Caladium Chantinii.

18. Aroideae.

19. Gloriosa Leopoldii.

20. This name has not been found in botanical reference works.

21. 'erect' interlined in ink.

22. This name has not been found in botanical reference works.

23. Costus Malortieanus.

24. Norysca chinensis.

25. Ixora javanica.

26. Capparis ferruginea.

27. Capparideae.

28. Amaryllideae.

29. Hugh Low was the proprietor of Hugh Low & Co., nurserymen, with premises at Clapton, London. After Low's death in 1863 the firm was conducted by his son, Stuart Henry Low (R. Desmond 1994).

30. 'micro?' interlined in ink.

31. Sarracenia variolaris.

32. Jasminum pauciflorum.

33. Higginsia argyroneura.

34. Higginsia pyrophylla.

35. Higginsia discolor.

36. Freycinetia imbricata.

37. 'Jus. Masc.': Jussieu. Mascarene Islands. The reference is to Antoine Laurent de Jussieu, who described the family Bignoniaceae ('Bignoniæ') in 1789 (Jussieu 1789, p. 137).

38. Rhinanthideae.

39. Asclepiadeae.

40. 'Ind. Or.': India Orientalis (East Indies).

41. Brexia madagascariensis.

42. An 'a' is superimposed in pencil on the final 's' in 'brachystachys'. CD mispelled Thryallis brachystachis.

43. Bougainvillaea speciosa.

44. Torenia pulcherrima, but the name has not been found in botanical reference works.

45. Asclepiadeae.

46. This name has not been found in botanical reference works.

47. Dipteracanthus Herbstii.

48. Allamanda Schottii.

49. Allamanda neriifolia.

50. Sapotae.

51. Lagerstroemia reginae.

52. Pleroma heteromallum.

53. Lythrarieae.

54. Justicia carnea.

55. This name has not been found botanical reference works.

56. Scrophulariaceae.

57. Justicia dicliptera.

58. Roxburghia.

59. Aroideae.

60. Pogostemon Patchouly.

61. Poinsettia pulcherrima.

62. This name has not been found in botanical reference works.

63. Sphaerostema marmoratum.

64. 'Ind. Occ.': India Occidentalis (West Indies).

65. Stylidium graminifolium.

66. Ficus aspera.

67. Adhatoda cydoniaefolia.

68. Justiciadae.

69. Vinca rosea.

70. Asclepiadeae.

71. This name has not been found in botanical reference works.

72. Singapore.

73. Plumbago zeylanica.

74. Sonerila margaritacea.

75. Scutellaria Trianaei.

76. Aroideae.

77. Anthurium cordifolium.

78. Ceropegia Gardneri.

79. Asclepiadeae.

80. Croton longifolius.

81. Croton variegatus.

82. Aeschynanthus. Species of the genus are tropical vines; CD mispelled 'lianas'.

83. Aeschynanthus Teysmanniana.

84. Possibly Aeschynanthus miniata.

85. Melastoma macrocarpum.

86. This name has not been found in botanical reference works.

87. Elaeis guineensis.

88. Coelebogyne ilicifolia.