Darwin is famous for showing that humans are just another animal, but, in his later years in particular, his real passion was something even more ambitious: to show that there are no hard-and-fast boundaries between animals and plants.

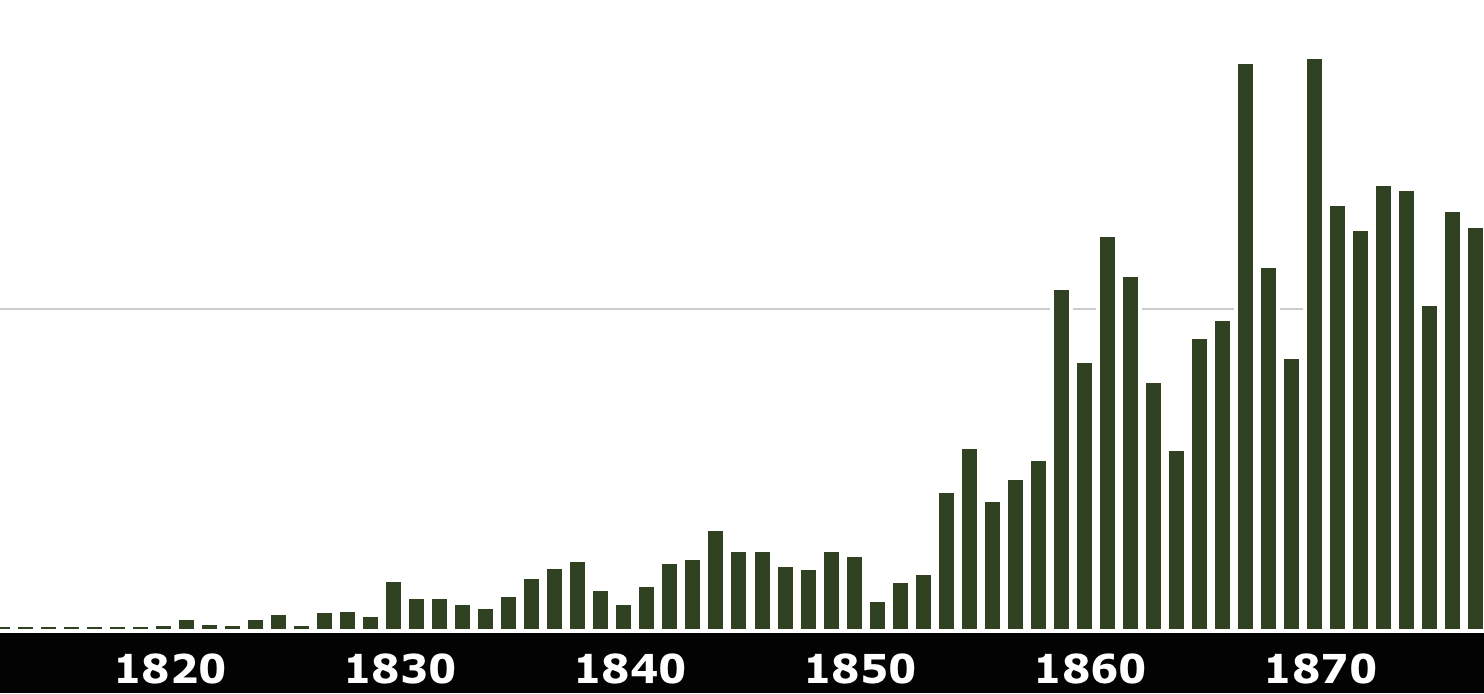

In 1875 Darwin brought out an unassuming little book of experiments, Insectivorous plants, that he didn't expect to be very popular: he was wrong. Then as now carnivorous plants - plants that turn the tables on animals by catching and eating them - caught everyone's imagination, spawning spoof stories of woman-eating plants, and carnivorous plant sellers exploiting the craze on the streets of London.* As a subject it had everything: food, murder, and fatal attraction.

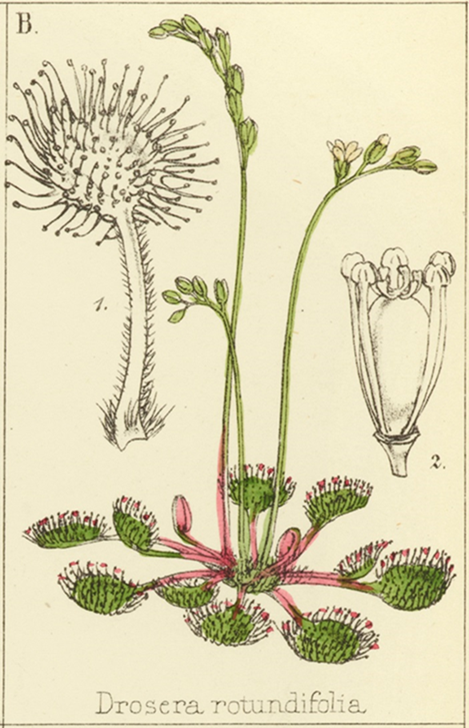

Darwin studied pitcher plants, Venus flytraps, waterwheels, butterworts, and bladderworts, but by far his favourite was the common sundew (Drosera rotundifolia). From the moment he spotted a patch while out walking on a family holiday, he was hooked. It was he said 'a wonderful plant, or rather a most sagacious animal' and he vowed to stick up for his 'beloved Drosera' to the day of his death. It was common knowledge that the sundew's tentacles were sticky, and that flies regularly got caught on them, but Darwin was curious about that stickiness and wondered if it had a use. He ended up by being the first person to demonstrate clearly that several species of plants can break down organic matter and absorb nutrients from it - in other words they can digest.

Like most of Darwin's work this research was wide-ranging, carried out over decades of tenacious observation and experiment, and it was collaborative. Together with naturalists and physiologists who were inspired by his work or co-opted by him, he identified and minutely described a whole world of cunningly adapted death-traps, from tempting sweet secretions, to slippery slopes, slamming trapdoors, spring-loaded vice, triggers, and vacuums.

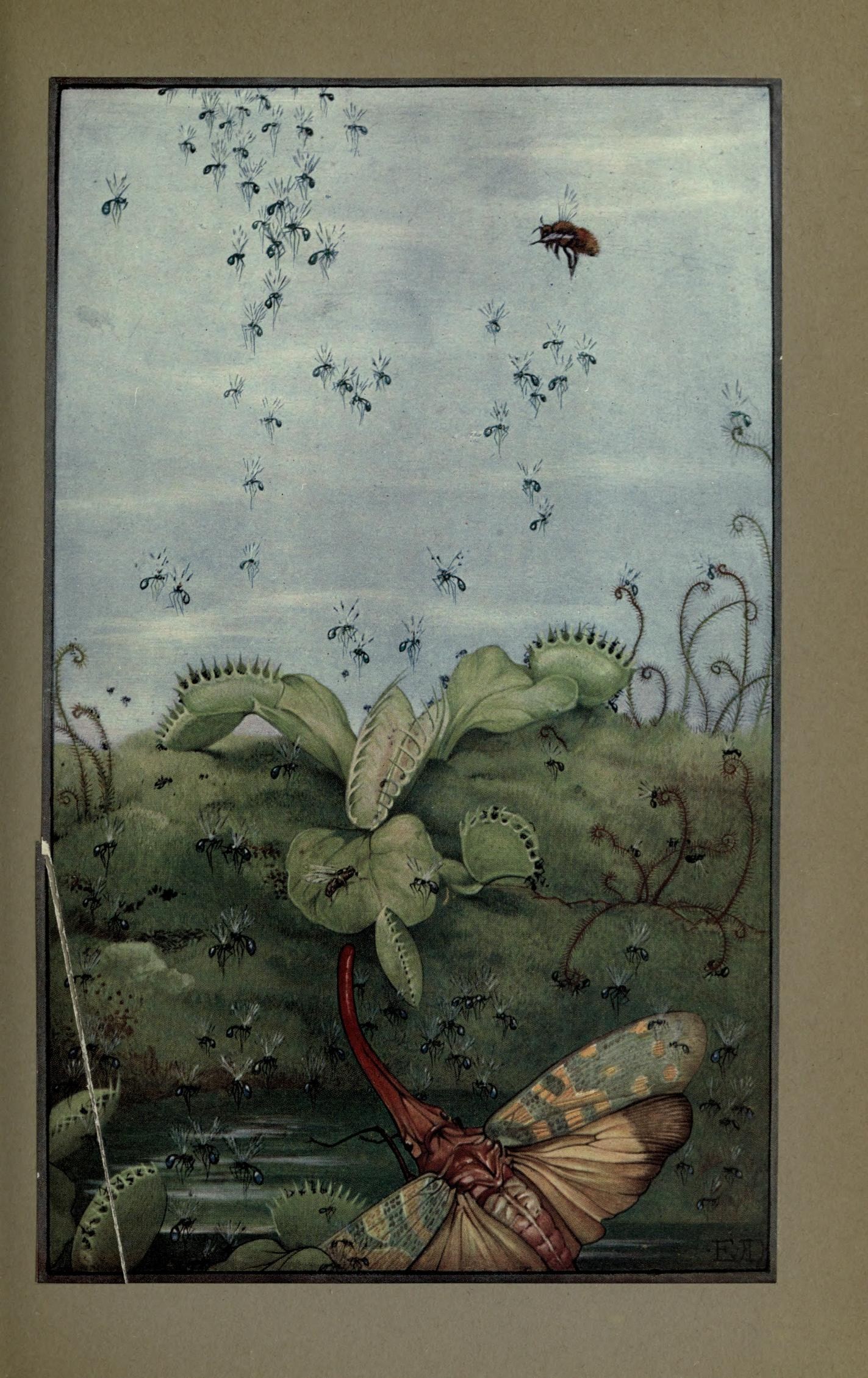

Venus flytrap from Maeterlinck, Maurice. 1917. News of spring and other nature studies. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/24189677

All of this was part of a wider research project on movement in plants. Darwin was looking for those traits that might show continuity between plant and animal kingdoms. We should think of plants, he said, not as organisms that cannot move, but organisms that have found clever ways to avoid having to do so. This is frontier stuff, and in many ways more subversive than anything else he did. It was also more fun. Darwin raided the kitchen, the medicine cabinet, the garden, and the lunch table in search of substances to feed to his pet plants. He tried meat (cooked and uncooked), egg, blood, urine, coal, gold leaf, and a whole Victorian poisoner's armoury - even cobra poison (Victorian homes had access to substances we definitely don't have). He even put them to sleep with chloroform (and if you are wondering what he was doing with chloroform, have a look at this letter about childbirth! He studied every stage of the process, looking not only at how insects were caught, but how they were attracted, how the different kinds of traps were able to move, and at the chemistry of the digestive fluids the plants secreted.

His obsession was so notorious that one of Darwin's friends poked gentle fun at him, writing a poem from the fly's perspective:

I never trusted Drosera,

Since I went there with a friend,

And saw its horrid tentacles

Beginning all to bend.

I flew away, but he was caught,

I saw him squeezed quite flat-

I don't go any more to Plants

With habits such as that.

* 'Since the publication of Darwin's last book, "Insectivorous Plants," one man, if no more (so the London newspapers tell us), has driven a thriving trade by selling on London Bridge the Drosera rotundifolia': Sophie B. Herrick, 'Insectivorous plants', Scribner's Monthly, April 1877, 804-15.