The charm of the place to me is that almost every field is intersected (as alas is our's) by one or more foot-patths- I never saw so many walks in any other country- The country is extraordinarily rural & quiet with narrow lanes & high hedges & hardly any ruts- It is really surprising to think London is only 16 miles off.-

To E. C. Darwin, [24 July 1842]

Charles and Emma Darwin, with their first two children, settled at Down House in the village of Down (later 'Downe') in Kent, as a young family in 1842. The house came with eighteen acres of land, and a fifteen acre meadow. The village combined the benefits of rural surroundings, where Darwin could make observations and undertake experiments in natural history, with reasonable ease of access to London, and was the environment within which Darwin's work over the last forty years of his life was almost exclusively conducted. The flower garden, kitchen garden, hothouse, orchard, meadow, and woodland with its circular sandwalk, all contributed at one time or another to Darwin's research. The countryside became his open-air laboratory and every walk became fieldwork.

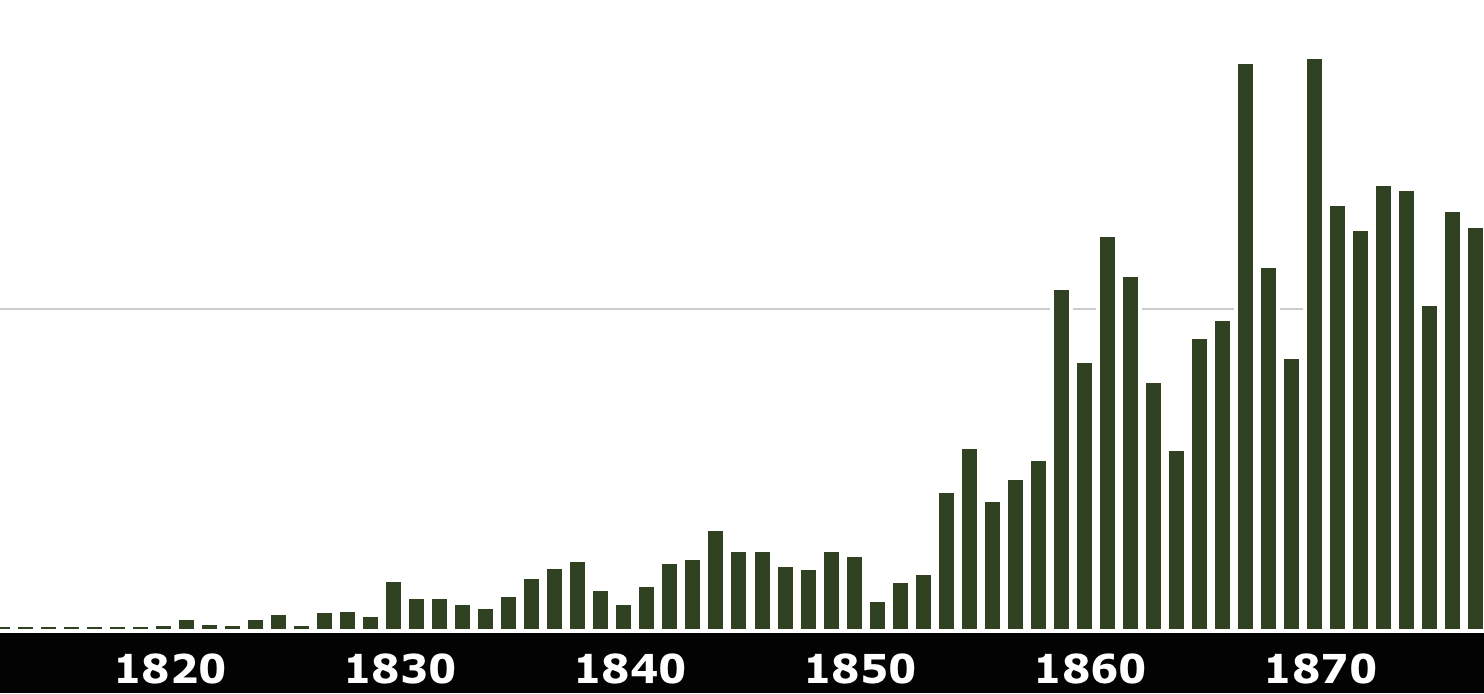

Altogether, Darwin wrote fifteen books and 130 scientific papers while he was living at Downe. He observed the interactions of plants and insects in the natural and semi-natural habitats of the woodlands and meadows around his home. In his garden and greenhouses, he cultivated plants from seeds obtained from around the world and devised ingenious experiments to study fertilisation (in particular the effects of crossing and of self-fertilisation); sensitivity in climbing, twining, and carnivorous plants; and competition between species. His last publication, The formation of mould through the action of earthworms (1881), was based on observations made over decades in his garden.

Many locations around Down identifiable from his letters and papers remain largely as they were in Darwin's lifetime, and comparisons can be made between the range of plant, animal, and insect life they supported in the nineteenth century, and the range they support today. The garden and grounds of Down House have been restored by English Heritage to reflect their state shortly before Darwin's death.

Selected letters:

If ever you catch quite a beginner, & want to give him a taste for Botany tell him to make a perfect list of some little field or wood……instead of the awful abyss & immensity of all British Plants.T

To J. D. Hooker, 15 [June 1855]

On the house and surroundings:

To his sister, Catherine Darwin, [24 July 1842]

To P. G. King, 21 February 1854: 'I live in the country about 16 miles from London, in a good large house, in a very solitary part of the country'

On plant diversity and the struggle for existence:

To J. D. Hooker, 5 June [1855]: Darwin describes the systematic collection of plants in a single habitat (now identified as Great Pucklands meadow) for his first study of plant diversity. Recent observations have demonstrated that the range of plants in the meadow remains much as it was in Darwin's day.

To J. D. Hooker, 3 June [1857]: on the struggle for existence in his own weed garden.

To Asa Gray, 5 September [1857]: setting out his ideas on the principle of divergence.

On cross- and self-fertilisation:

To Asa Gray, 5 September [1857]: on Lobelia and kidney beans

To J. D. Hooker, 28 September [1861]: on Verbascum 'I do not think any experiment can be more important on Origin of species'

On plant sensitivity:

To Charles Lyell, 24 November [1860]: describing experiments on Drosera (sundew): 'at this present moment I care more about Drosera than the origin of all the species in the world'.

To J. D. Hooker, 25 [June 1863]: describing the light-sensing behaviour of plants on his windowsill.

On co-adaptation:

To J. D. Hooker, 12 July [1860]: on adaptation in Orchis pyramidalis.