Why Orchids?

Darwin wrote in his Autobiography, 'During the summer of 1839, and, I believe, during the previous summer, I was led to attend to the cross-fertilisation of flowers by the aid of insects, from having come to the conclusion in my speculations on the origin of species, that crossing played an important part in keeping specific forms constant.' While his subjects for observing crossing were wide-ranging, one group would captivate Darwin like no other. In June 1855, Darwin added a postscript to a letter to his close friend Joseph Dalton Hooker. He wrote, 'I have been watching impregnation of Orchideæ & there is something about the visits of insects which quite puzzles me.- The Fly-Ophrys seems hardly ever to get its pollen masses moved at all, & the germens swell when plant has been covered by Bell glass.' So began Darwin's interest in the floral morphology of orchids, but it was another few years before the puzzle would again bubble to the surface of Darwin's mind. By 1858, Darwin had examined over a hundred individual flowers of Ophrys muscifera (a synonym of O. insectifera, the fly orchid) and noted that only a small fraction ever had their pollinia removed. This could have been the beginning of a period of intense orchid research, but June 1858 brought a letter that changed Darwin's focus dramatically. Alfred Russel Wallace sent him a paper entitled 'On the tendency of varieties to depart indefinitely from the original type'. The manuscript of that paper has yet to be found, but it was published as part of a joint paper by Wallace and Darwin, and led to Darwin's rush to publish an 'abstract' of his theory, On the origin of species.

Following the publication of Origin, Darwin appeared eager to start work on the first part of what he had planned to be his 'big book' on species theory. He noted in his journal on 9 January 1860, 'Began looking over M.S. for Work on Variation (with many interruptions)'. 'Many interruptions' turned out to be a considerable understatement, since not one but two other works appeared before Variation was finally published in 1868. The first of the 'interruptions' was a small book with the rather long title On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fertilised by insects, and on the good effects of intercrossing. The 'Orchid book', as Darwin usually referred to it, appeared in May 1862 (Orchids).

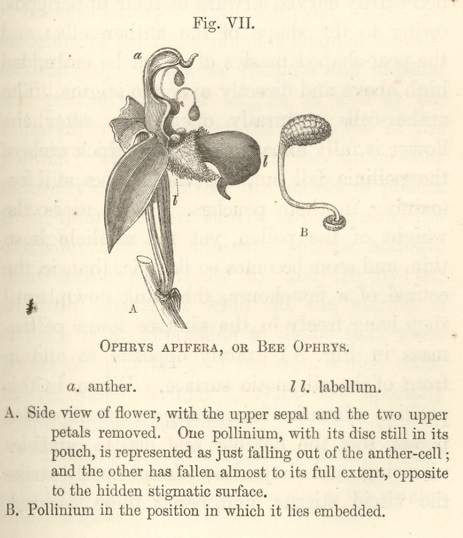

A letter to Hooker, on 5 June [1860] reveals why orchids might, once again, have piqued his interest. Darwin wrote, 'You speak of adaptation being rarely visible though present in plants: I have just recently been looking at common Orchis, & I declare I think its adaptations in every part of flower quite as beautiful & plain, or even more beautiful, than in Woodpecker.' But at least one orchid was problematic. Darwin continued, 'I have written & sent notice for Gardeners' Ch. on curious difficulty in Bee Orchis, & shd. much like to hear what you think of the case.' Indeed, Darwin had just sent a long letter to Gardeners' Chronicle asking readers to observe the orchid. In it he concluded, 'It is this curious apparent contradiction in the structure of the Bee Orchis-one part, namely the sticky glands, being adapted for fertilisation by insect agency-another part, namely the natural falling out of the pollen-masses, being adapted for self-fertilisation without insect agency-which makes me anxious to hear what happens to the pollen-masses of the Bee Orchis in other districts or parts of England.'

Not content with alerting gardeners to the problem, Darwin hoped to enlist readers of the Entomologist's Weekly Intelligencer, and wrote to the editor, Henry Tibbats Stainton, for help: 'I fear it is quite out of the question your being able to insert the whole [of the letter to Gardeners' Chronicle] in the Intelligencer; but perhaps you would oblige me by putting in the paragraph in which I ask for information on what kinds of moths the pollen-masses of Orchids have been found adhering.' The complete letter to Gardeners' Chronicle was reprinted in the Entomologist's Weekly Intelligencer, in issues for 23 and 30 June 1860. Looking even further afield, Darwin sent a copy of the letter to Asa Gray, remarking, 'Talking of adaptation, I have lately been looking at our common orchids & I daresay the facts are as old & well-known as the hills, but I have been so struck with admiration at the contrivances, that I have sent notice to Gardeners Chronicle. The Ophrys Apifera, offers, as you will see, a curious contradiction in structure.'

The letter to Asa Gray highlights an important factor leading Darwin to write his study of orchids. After mentioning his observations on orchids, Darwin continued, 'I get on very very slowly with my larger work; & of late from a very unhappy cause, my poor eldest daughter about 16 years old, has now been 40 days ill with low fever: we have had a good deal of anxiety, but I hope & think she has at last turned the corner, though the fever has not gone.' One might speculate that the research on orchids provided a welcome break from the 'larger work' and the worry over his daughter Henrietta's illness.

Gathering Evidence

The conundrum of the bee orchid was only one curious point. Darwin soon approached Hooker with another observation, pleading, 'Have pity on me & let me write once again on Orchids for I am in a transport of admiration at most simple contrivance, & which I shd. so like you to admire.' This time, the point of interest was the structure of the stigma in Gymnadenia conopsea (the fragrant orchid), which Darwin went on to describe in detail. He even dared to challenge George Bentham's classification of the species in a different genus (Orchis) based on this observation. By now, the subject of orchids was irresistible; towards the end of June 1860, Darwin approached the botanist Alexander Goodman More, who lived on the Isle of Wight, asking him to observe the bee orchid, and requesting flowers of some other orchids found on the island. Since More was not an acquaintance, Darwin hesitated, but ventured, 'Could you oblige me by taking the great trouble to send me in an old tin cannister any of these orchids, permitting me of course to repay postage. It would be a great kindness, but perhaps I am unreasonable to make such a request.'

By early July 1860, More had provided fresh specimens, the first of many, as it turned out. No sooner had he thanked More for this initial offering, Darwin added, 'I shall be most grateful for the E. palustris and it will be all the better for me in 10 days time. Please see that there are some buds; as these are the best in some respects for points of structure which I am examining.' Several more shipments followed and a year later, referring to the specimens of Epipactis palustris (marsh helleborine), Darwin told More, 'The examination of that species has been one of my greatest treats, which I owe to you. I fear I am very unreasonable; but this subject is a passion with me.' Unfortunately, although More could send specimens of various orchids, Darwin had to infer the role of insects from the floral architecture. For this reason, Darwin increasingly wrote to ask for field observations as well as specimens, describing in detail what he wanted More to observe. More's side of the correspondence has not been found, but many of his observations cited in Orchids are responses to the queries that Darwin posed in his letters.

Darwin was still mostly focused on the fact-gathering stage of his research, but in August 1860, he wrote an 'abstract' that related to his evolutionary interpretation of floral structure. He told Hooker, 'I am convinced that your Listera discovery is the key-stone to understand the structure of many orchids.- I enclose abstract of facts of two cases. … observe what little change would convert Epipactis to Orchis: the temporary or non-congenital point of attachment in working down to base of pollinia; & to viscous matter (at least greater part) does not come out of the rostellum.' He then requested more specimens, explaining, 'I suspect that the slow movement in one direction which I find in all pollinia of Orchis, would explain the springing out of pollinia in Catasetum. Could you lend me a plant in bud & bloom of Catasetum?' Listera ovata (common twayblade) had been the subject of Hooker's 1854 paper on the functions and structure of the rostellum (a projection in the column of an orchid that separates the anthers from the fertile stigma). Darwin's growing confidence is evident from the ease with which he dismissed Hooker's interpretation of the functional significance of this structure in a letter to More on 5 August 1860, 'Dr. H. is considerably mistaken about the use of the parts, but his facts are accurate; and it is following out the remarkable modification in the structure and function of the rostellum, that I am so anxious to examine Spiranthes and Epipactis and indeed all Orchids. The paper is really worth reading, though the facts in several respects are far more curious than Hooker suspected.'

'At some distant period'

The case of Listera highlights an important difference between Darwin's approach and that of a more traditional botanist like Hooker. Writing to Daniel Oliver in October 1860, Darwin explained, 'I am much obliged to you for so kindly telling me about the Australian Orchids, (a subject which interests me greatly, & I have now examined nearly all the British kinds); but I cannot quite understand the description, & without examining the live plants, with reference to visits of insects, I believe their means of fertilisation can never be understood. Even Hooker was led into considerable error, not of facts, but of purpose in his curious description of Listera.' A week later, Darwin told Oliver, 'I really know nothing whatever about vegetable irritability (it is quite beyond my scope) except in case of Orchids; I have a large mass of notes with many new facts, but I resolutely, against my inclination, put them away a month ago with the determination to work them up & get drawings made at some distant period; for I am convinced that I ought to work on Variation & not amuse myself with interludes.'

Darwin's resolution was short-lived, for, by the end of October 1860, with Henrietta having suffered a dangerous relapse in the interim, he wrote a long letter to his American friend Asa Gray, describing in detail the movement of the pollinia in Orchis pyramidalis (a synonym of Anacamptis pyramidalis, the pyramidal orchid) and Spiranthes autumnalis (a synonym of S. spiralis, autumn lady's tresses). As Henrietta's health continued to improve, Darwin once again resolved to focus on his larger work as well as revising Origin for a third edition. By the end of May 1861, Darwin recorded further progress on Variation, but during two summer months spent in Torquay, he wrote his first draft of what was intended as a paper on orchids. He confessed to Hooker, 'My paper, though touching on only subordinate points will run, I fear, to 100 M.S. folio pages!!! The beauty of the adaptations of parts seems to me unparalleled. ... It is mere virtue which makes me not wish to examine more orchids; for I like it far better than writing about varieties of cocks & Hens & Ducks.' Without missing a beat, he continued, 'Nevertheless I have just been looking at Lindleys list in Veg. K. & I cannot resist one or two of his great Division of Arethuseæ, which includes Vanilla. And as I know so well the Ophreæ, I shd like (God forgive me) any one of the Satyriadæ, Disidæ, & Corycidæ.'

The holiday in Torquay seems to have been a turning point. Darwin recorded in his Journal for 1861, 'During stay at Torquay did paper on Orchids all rest of year Orchid Book' -as was so often the case with him, Darwin could not stop adding material, so the paper soon became a book. The 'distant period' was reached far sooner than expected.

'Any woman could read it'

By September 1861, Darwin was ready to pitch this new study to his publisher, John Murray; after mentioning his original plan to publish in the Journal of the Linnean Society, Darwin noted, '… yesterday for the first time it occurred to me that possibly it might be worth publishing separately, which would save me trouble & delay.' The audience projected was broad: 'The subject of propagation is interesting to most people, & is treated in my paper so that any woman could read it.' A modern reader might view the last remark as condescending, but Darwin did not intend that. At this time, many women were avid collectors of orchids and very knowledgeable about propagation. Indeed, one of Darwin's most valuable correspondents, as he broadened his project to include tropical orchids, was Lady Dorothy Nevill, an accomplished horticulturalist, who provided him with several exotic specimens. Darwin must have been fairly confident that Murray would agree to publish, since he mentioned that he had already hired an artist to make drawings for the illustrations. On the other hand, he worried that if the book were to fail it might injure sales of future larger books. He need not have been concerned as Murray replied, 'I have no hesitation in offering to print & publish the work including Illustrations at my own sole cost & risque giving you one half of the profits of every Edition.'

Darwin replied to Murray, 'I think this little volume will do good to the Origin, as it will show that I have worked hard at details, & it will, perhaps, serve [to] illustrate how natural History may be worked under the belief of the modification of Species.' The content was not the only part of the book that concerned Darwin, though, since he proposed to add a gold orchid to the cover of the edition. The published book was a departure from the sober green binding that graced all his other works; the cloth was plum-coloured with a gilt orchid on the front. The flower depicted was a male Cycnoches (swan orchid), with which the printer was evidently unfamiliar since the image is printed upside down (see image above). Having now been given the go-ahead, Darwin quickly arranged for his illustrator to begin work. George Brettingham Sowerby Jr arrived at Down on 7 October 1861; five days on, Darwin told his son, William, 'I am half-dead with working with Mr Sowerby at the Orchid drawings'. He worried, 'The drawings will be pretty successful; but I feel sure that my little book will be too difficult & too uniform for the Public & I almost wish I had never thought of separate publication.'

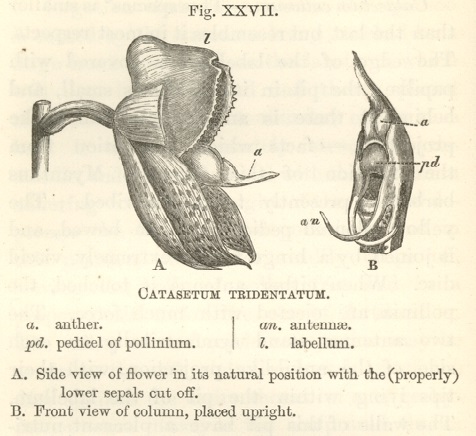

By this time, Darwin had become increasingly interested in exotic orchids, so much so that the one change Murray decided to make to the original title was to add 'and foreign' before 'orchids'. Darwin had approached Lady Dorothy Nevill at the suggestion of John Lindley, the horticultural editor of Gardeners' Chronicle, and was rewarded with several specimens. He told Lindley, 'Lady Dorothy has written me one of the most obliging notes, I ever received, & has sent a lot of orchids now on the road!' Typically, the first shipment led to further requests, together with detailed instructions for packing the rare specimens. Darwin confessed, 'I am convinced that orchids have a wicked power of witchcraft, for I ought all these months to be working at the dry old bones of poultry, pigeons, and rabbits instead of intensely admiring beautiful orchids.' Lindley provided Darwin with the name of another collector, Sigismund Rucker, who was able to lend Darwin a plant of Mormodes ignea, a Central American species that puzzled Darwin with its curious appearance and even more unusual mechanism. Darwin had earlier told his friend Hooker, 'I shall never rest till I see a Catasetum eject pollen-masses, & a Mormodes twist its column.'.

Catasetum was of special interest to Darwin, not only because of its remarkable ability to eject its pollen masses like a catapult, but also because of its different flower forms. While the vast majority of orchid flowers are hermaphrodite, those of Catasetum and related genera like Mormodes and Cycnoches have separate male and female flowers. Even more remarkable was the widely different appearance of the different sexual forms in Catasetum, so much so, that these had been given specific status by earlier authors. As Darwin was able to study specimens sent by the nurseryman James Veitch as well as Hooker and Rucker, his letters at first focused on the ejection mechanism but by late 1861 he began to suspect that some of the flowers of Acropera (a genus now subsumed within Gongora) he had been examining were male, and further, that he would be able to make out separate sexes in Catasetum and Myanthus. In a letter to Daniel Oliver in December 1861, Darwin revealed that he thought 'Catasetum tridentatum is male Monacanthus viridis-female Myanthus barbatus-Hermaphrodite & you know they have been produced on same plants.'

As 1861 drew to a close, Darwin's friends were already anticipating the publication of his little book. Asa Gray wrote, 'I am going to ask you to send me by mail the sheets of your little Orchid book-one by one-as soon as they come out.-I may want to write an early notice of it, and need time to ponder its teachings.' Darwin summed up his feelings about the book in his reply: 'I fear that you expect in this opusculus much more than you will find- I look at it as a hobby-horse, which has given me great pleasure to ride. I will with great pleasure send you the sheets if I can … I shall be very curious to hear what you think of it; for I have no idea whether it has been worth the trouble of getting up,-though the facts, I am sure, were worth my own while in making out'. He had earlier confessed to Lindley, himself the author of a number of works on orchids, 'I very much fear that in publishing I am doing a rash act; but Orchids have interested me more than almost anything in my life.'

By February 1862, Darwin was able to send the manuscript of all but the last chapter of his book to his publisher, noting, 'I can say with confidence that the M.S. contains many new & very curious facts & conclusions.- I have done my best to make the facts striking & clear. I think they will interest enthusiasts in Nat. History; but I fear will be too difficult for general public.' In March, as he finished correcting proof-sheets, he told Hooker, 'You will be disappointed in my little book: I have got to hate it, though the subject has fairly delighted me: I am an ass & always fancy at the time that others will care for what I care about: I am convinced its publication will be bad job for Murray.' But Darwin never regretted his study, for as he confided to Hooker, 'I have found the study of orchids eminently useful in showing me how nearly all parts of the flower are coadapted for fertilisation by insects, & therefore the result of n. selection,-even most trifling details of structure.' Orchids was published in May 1862.

'A new and unexpected track'

Even before his book on orchids reached the general public, Darwin had excerpted material for a paper that he presented himself to the Linnean Society on 3 April 1862, 'On the three remarkable sexual forms of Catasetum tridentatum, an orchid in the possession of the Linnean Society'. The paper evidently caused a stir, for Hooker wrote, 'How are you after your tremendous effect on the placid Linnæans?' Darwin responded, 'I by no means thought that I produced a "tremendous effect" on Linn. Soc; but by Jove the Linn. Soc. produced a tremendous effect on me for I vomited all night & could not get out of bed till late next evening, so that I just crawled home.' Just over a month later, Orchids was published. Sales were slow, but the book had a positive reception. Daniel Oliver, who was professor of botany at University College London, commented, 'It is a very extraordinary book! ... I am just now, you know, busy with my Class that I have very little time to spare, but shall not fail to inform them of your general results.' George Bentham recognised the wider implications of the study, noting, 'I have only had time as yet to go through the first two chapters but they are quite enough to show what a new field for observing the wonderful provisions of Nature you have opened-as the notice you gave of a portion of it at a recent Linnean meeting put us on a new and unexpected track to guide us in the explanation of phenomena which had before that appeared so irreconcileable with the ordinary prevision and method shown in the organised world.' Hooker summed up their reaction: 'Bentham & Oliver are quite struck up in a heap with your book & delighted beyond expression'.