How do new species arise? This was the ancient question that Charles Darwin tackled soon after returning to England from the Beagle voyage in October 1836. Some naturalists, such as Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and the medical writer Erasmus Darwin (Charles Darwin's grandfather), had thought that new species of animals and plants emerged through a progressive evolutionary force beginning with the spontaneous generation of life. The astronomer John Herschel had called it 'the mystery of mysteries.' Others believed such subjects were beyond the bounds of science. Recording his observations and increasingly bold thoughts in a series of private notebooks, the young naturalist began exploring the world of animal and plant breeders, in the hope that their practical knowledge would shed fresh light on the problem.

In September 1838, Darwin realised a crucial (and cruel) fact: far more individuals of each species were born than could possibly survive. What led some deer to die during a harsh winter, and others to survive and reproduce? Darwin's answer was that some were better adapted for particular circumstances than others. Within each species of animal or plant, it was possible to find a remarkable range of variation: no two individuals were the same. Only the best adapted would survive to reproduce and pass down their characteristics to the next generation. A slightly heavier coat, a better ability to run from predators: these could make all the difference. Over a long period of time, these tiny changes would accumulate, thus leading to new species.

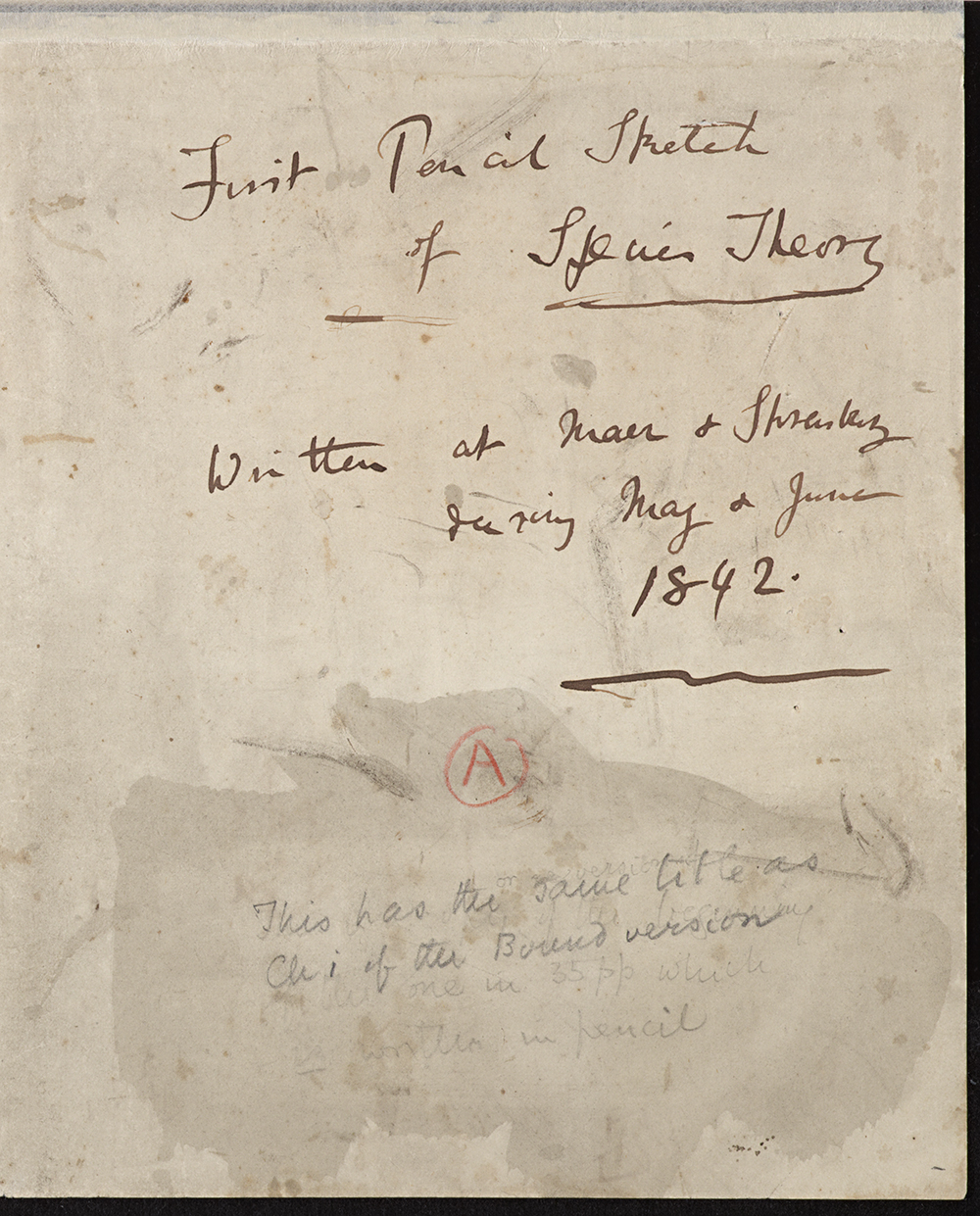

This is what Darwin, through an analogy with 'artificial selection', came to call the principle of 'natural selection'. As he explained in On the Origin of Species (1859), nature was like the breeders whose works he had studied so carefully. A skilled breeder would select individuals with tiny but desirable variations, and allow only those to produce offspring. Continued over many generations, this process could produce differences as wide as those between the Great Dane and the dachshund. Nature, Darwin realised, worked in the same way, but more rigorously and over a far longer time scale. As Darwin recalled at the end of his life, 'being well prepared to appreciate the struggle for existence. . . it at once struck me that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved & unfavourable ones to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species.' Death, Darwin had unexpectedly realized, was the secret to the great tree of life.

Darwin made his discovery not in isolation on the Galapagos or on the Beagle voyage, but as a twenty-nine year old bachelor living in cheap housing in London. This was 'modern Babylon', the largest city the world had ever known. It is not surprising, then, that Darwin reached his insight while thinking about people. As part of a broader interest in metaphysics, psychology and economics, he read Thomas Malthus's controversial Essay on the Principle of Population (6th edition, 1828); Malthus argued that famine and disease were necessary to keep human populations in check. Although for tactical reasons humans are mentioned only briefly in Origin, Darwin did publish his full thoughts in The Descent of Man (1871), his last great theoretical work on species.

In the two decades following his insights of the late 1830s, Darwin undertook research on virtually every aspect of his theory. He soaked seeds in salt-water to study the possibility of long-distance transport in the oceans; raised pigeons to understand the effects of crossing; and worked on the classification of barnacles, which reinforced his appreciation of just how much variation there is in nature.

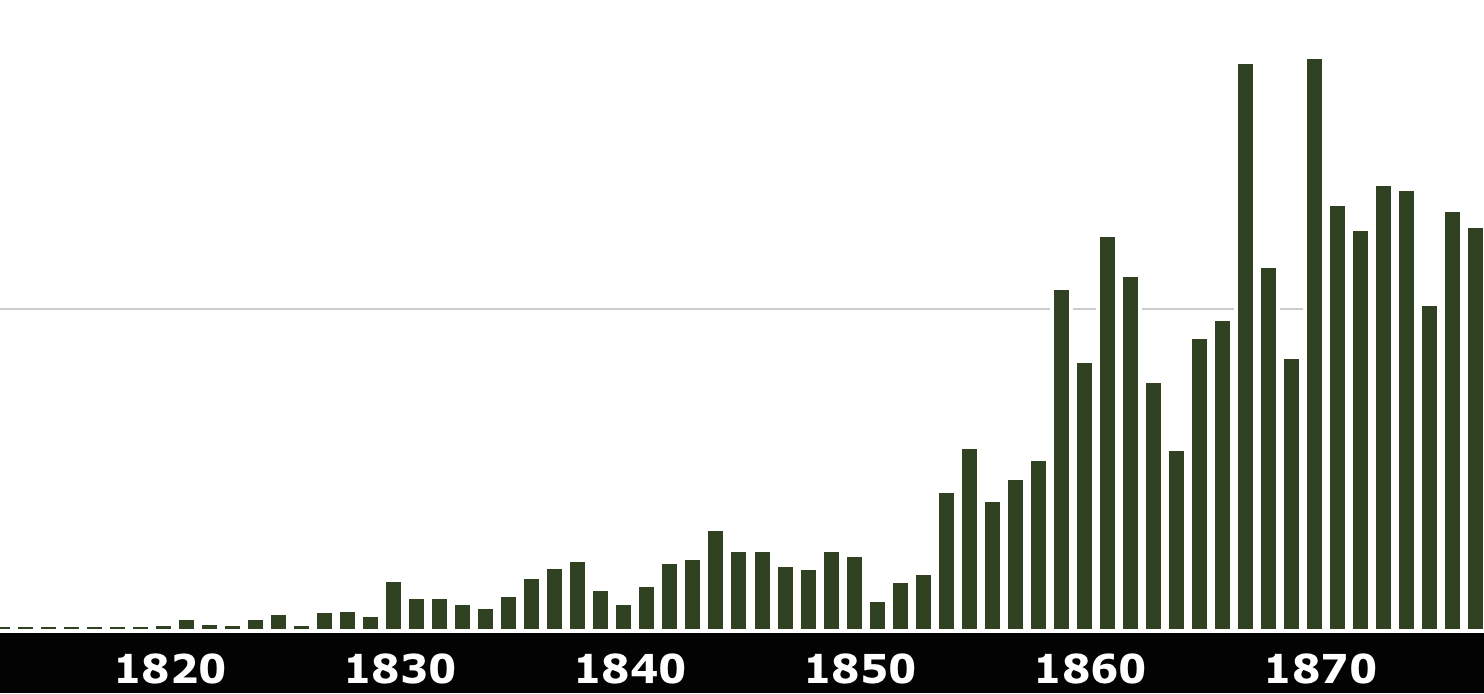

While Darwin waited to publish his ideas, the problem of species became the subject of ferocious public debate. The journalist Robert Chambers's anonymous Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, published in 1844, moved discussion of evolution out of medical dissecting rooms and the radical freethinking press, into Victorian homes. Vestiges suggested that a law of development could explain everything from the orgins of the solar system to the human mind.

Having read Vestiges, and inspired by Malthus, in 1858 the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace came up with a species theory remarkably similiar to the one that Darwin had been elaborating for so long. The work of both men was announced in 1858 at a meeting of the Linnean Society of London, and Darwin immediately set to work on what became On the Origin of Species. Wallace went on to produce many important scientific works, particularly on the geographical distribution of species and the questions raised by what he generously termed 'Darwinism'.

Origin, published in 1859, transformed the public controversy about species and creation. Even those who were not fully convinced-like the ambitious young man of science Thomas Henry Huxley-recognised Darwin's theory as the first attempt to tackle the problem that could not simply be dismissed as idle speculation. In large part this was because natural selection provided (as Darwin later said) a 'theory to work by', one that suggested practical possibilities for research in the laboratory and field.

In part, this was because of Darwin's own status as a man of science. For the rest of his life, Darwin continued to publish books and papers relating to his theory. Besides two volumes on human evolution, he wrote extensively on variation in domesticated animals and plants, and explored topics ranging from orchids and earthworms to carnivorous plants and the expression of the emotions. Much of this work was conducted through correspondence, and his ability to call on supporting evidence from all over the world gave the theory unprecedented scope and power.

From the beginning, Darwin was aware of the complexities of the questions he was attempting to solve. For him, natural selection was always only the most significant among the many factors that led to new species. The apparent effect of the environment had to be explained, as did the impact of changes on the reproductive organs, and differences between the sexes. Generation and heredity are thus significant elements in his theories, both in the opening chapters of the Origin and in Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication (1868), which developed his much-criticized theory of inheritance ('pangenesis').

Today, natural selection remains at the core of discussions about species, and evolution is central to scientific fields ranging from population biology and psychology to laboratory genetics and genomics. Like any successful theory, natural selection has been transformed, questioned and developed over the century and a half since it was first proposed. But the basic insight has survived, to a degree that is almost unprecedented in the history of science. As Darwin recognised from the start, understanding natural selection is also essential to understanding our own origins and destiny: thinking about species involves thinking about ourselves.

Related Resources: