John Hedley Brooke is President of the Science and Religion Forum as well as the author of the influential Science and Religion: Some Historical Perspectives (Cambridge University Press, 1991). He has had a long career in the history of science and religion, and was the first Andreas Idreos Professor of Science and Religion at the University of Oxford.

Date of interview: 12 March 2009

Transcription

1. Introduction

Dr White:

This is [part of] a series of interviews that is hosted by the Darwin Correspondence Project about Darwin and religion. My name is Paul White and with me here today is John Hedley Brooke, who has written a very influential work and had a long career in the history of science and religion and until recently was a professor of science and religion at Oxford? and it's very nice to have you here, John. Thank you for coming.

Prof. Brooke: Thank you, Paul. It's a very great pleasure.

2. Victorian spiritualism and the boundaries of science

Dr White:

I'd like to start with a question about the boundaries of science ? and this is a question raised in a debate in Darwin's day. I'm not thinking of the more familiar debate over Paley's natural theology; but rather of a debate that takes place later in the 19th century, over spiritualism. Darwin's close scientific colleague and friend, Alfred Russell Wallace becomes interested, and eventually engrossed, in spiritualism. He first writes to Darwin about this in 1869, and this is exactly the same time that he makes his first major criticism of the theory of natural selection as applied to humans, arguing that natural selection cannot explain certain mental powers and physical structures, and that these are better explained by the action of a higher power. Darwin is clearly shocked by this, and Wallace works very hard to convince him that he hasn't given up the path of science: that in fact there is good scientific evidence for the existence of spiritual powers. And Wallace goes on in later years to campaign for this; and there were a number of other men of science who became involved in the movement. So, my question is whether you could say a bit more about the curious status of spiritualism in the Victorian period?as both a religion, and a science. In what sense was it open to scientific investigation, and were Wallace and others partly calling for a more expansive approach to science itself, one that might allow for spiritual agencies?

Prof. Brooke: It's a deeply interesting question, Paul, and very challenging. Looking back on that episode in late Victorian thought and culture, it can strike us today as very odd indeed that a scientist of Wallace's calibre was actually interested in exploring this spritual realm at all. And it does seem to me in retrospect that this harmed his reputation, scientifically. We tend to think always in terms of Darwin as the great scientist and Wallace as getting sidetracked into this domain.

What I think is important to recognise is that you could see this spiritualism movement as a desire to clarify what the real entities are in the universe. Is the world of nature simply a collection of material bodies, or is there some other kind of invisible realm which can interact with the material [one]? I think as a form of popular religion, we can understand it, as one of very many forms of popular religion in that period. I think we know that there were attempts to establish the existence of some kind of life after death through communion with spirit agencies that had now departed this world. So there is a very serious question about whether, for example, the human mind and its operations can be understood simply in terms of matter in motion, or whether our powers of thought - our powers to motivate ourselves - do actually indicate the existence of something beyond the material.

It's striking, I think, that scientists like Charles Lyell, for example, felt, also, that there were features of the human mind which were rather difficult to explicate purely in terms of natural selection. For Wallace, of course, the fact that we have aesthetic appreciation: we can appreciate beauty in nature, we have mathematical skills, we enjoy music, for example? and for Wallace, these were clearly features of the human person that he felt could not be explained by natural selection alone because it wasn't clear what kind of survival value they could be said to have when these particular talents were not distributed uniformly across the whole of the human race.

So I think we are dealing with a very interesting phenomenon here, which can possibly also in part be explained in terms of the vacuum that had been created - for some people - by the challenge to Christianity that had come earlier in the century from various sources. And if you gave up an orthodox Christianity, as Wallace had certainly done early in his life, then there is a sense in which one might be looking for some kind of spiritual realities that would help to fill that vacuum.

Wallace, I think, did feel quite genuinely that you could perform scientific experiments at least to test whether the claims of certain - um - figures who manipulated tables and claimed to make contact with some other world? whether these claims could actually be substantiated. And when he was reproached for taking science into this territory, he put on the hat of any normal empiricist, saying that we can actually check whether we have got some phenomenon here that illustrates the direct interaction between a spiritual reality and a material reality.

3. Parallels between Victorian spiritualism debates and intelligent design debates today

Dr White:

I want to draw a parallel here between the spiritualism debate in the 19th century and the debates over intelligent design today. Here again some have raised the question of the boundaries of science: is intelligent design a science or is it religion in disguise? If it is science, then this might well have implications for how science is defined, particularly the role that intelligent design seems to allow for divine, supernatural, or purposeful agency. Do you think this is a fair comparison? Do you see the intelligent design

debate as partly turning on this question of the boundaries of science, and do you see a resolution to this question?

Prof. Brooke: I think there is a very striking and rather obvious parallel, in the sense that advocates of intelligent design today - in its negative aspect - do suggest that there are features of the Darwinian mechanism of natural selection which are themselves inadequate to account for the complexity of organs and biochemical processes. When one looks at that sort of claim, it strikes one immediately as a kind of gaps argument: that there's something here that science can't explain, and so let's invoke something else: the work of some kind of intelligence behind the process. So that clearly does bear a resemblance to the arguments in the 19th century over whether there was some kind of spirit agency guiding the process of evolution.

Darwin himself, of course, resisted that notion because he felt it would be, somehow, to detract from the power of natural selection if you suggested there were other agencies at work in nature. So I do see a certain parallel there. And the question today certainly does turn in part on What is science? What is religion?

There are particular reasons, I think, stemming from the American constitution why the question tends to get reduced to that. Is the affirmation of intelligence religion or is it science? One might want to suggest that it really belongs to a discussion in philosophy or metaphysics rather than science or religion per se.

I think it's been a traditional move to make amongst informed critics of ID that it can hardly pretend to be serious science because it doesn't make predictions that can be tested in the way that most scientific research programs can. In other words, it seems like a rather sterile kind of philosophy. To want to call it science may be too optimistic on the part of its adherents. There is, however, a complication about this, which is that philosophers of science have tried for many, many years to find some critical demarcation criterion that enables us to say of this

that it is science and of this that it is pseudo-science. And most of those attempts, it's fairly generally agreed, are not entirely successful.

There is an interesting approach to this issue, which other philosophers of science have now taken up, which instead of suggesting that intelligent design cannot be a form of science? they will concede that there is perhaps a sense in which it is?or a sense in which it was, and this is the nub of the issue, because they would argue that intelligent design is actually a reversion to an older form of science which is now obsolete: it's dead; it's been superseded, in part by the kind of science that we find within the Darwinian tradition. I think such philosophers would be perfectly happy to concede that the affirmation of some kind of intelligence behind nature once was constitutive of scientific practice and belief.

An obvious example would be the way in which 19th century paleo-biologists, for example, would reconstruct the forms of extinct species just from the fragments of their fossil remains because what was guiding them was the notion that the organism was, in some sense, optimally designed and they could reconstruct the whole in the light of its parts and with that kind of design presupposition. But I think it's perfectly correct to say we could write a history of concepts of design, and a history of evolutionary science which would show how that approach - belief in design, allegedly manifest within a living organism - was gradually found unnecessary.

So, the upshot of this rather long response to the question, is that it is possible to see intelligent design as a form of science, but it's actually dead science: it doesn't go anywhere. And so, I would see it, actually, as a contraction of the limits and scope of science rather than as an expansion, whereas I think there was, perhaps, a sense in which in the 19th century in debates over spiritualism there really was a genuine attempt to expand the number of kinds of thing that there was, or were, in the universe. And spirit agencies might be invisible, but the notion that they could interact with the human mind didn't seem so far-fetched to those who were concerned about that problem.

4. Patterns in the response to Darwin

Dr White:

We know, partly from your own work, that the religious response to Darwin was very diverse: by no means a simple antagonism; sometimes a very warm reception. Do you think there were any patterns to this? Religious traditions, denominations, theologies that were more inclined to accomodate Darwinism than were others? Or are we looking at just a vast set of very individual responses?

Prof. Brooke: Well, I'm tempted to say in reply to that that we are looking at some very individual responses. And I say that, because studies have been made attempting to achieve some kind of correlation between specific religious traditions and their attitudes towards Darwin. I think it's fairly obvious that if you wished to retain a literal interpretation of the Genesis creation narratives, for example, then you would be predisposed against the Darwinian theory. That can happen in various conservative elements within various religious traditions. One's tempted to say that it's within the evangelical traditions particularly, where there might be a suspicion of the Darwinian theory on that ground. And I think possibly also for the evangelical thinkers, there was concern about our fallen state. In their theology, humankind has rebelled against its creator, and there is a sense in which the world is not as God intended it to be. And if one thinks of the world as fallen, and as of humankind as fallen, that might be rather difficult to reconcile with the Darwinian image of some kind of ascent from animal ancestors to creatures like ourselves. So there are obvious factors of that kind which I think do predispose certain factions within the churches to take the line that they do. And while we're just thinking about conservative responses, there were of course those who felt that the bible told you more or less all you needed to know about the topic and that it was rather presumptuous of scientists to come up with some alternative, but I do think they were in the minority.

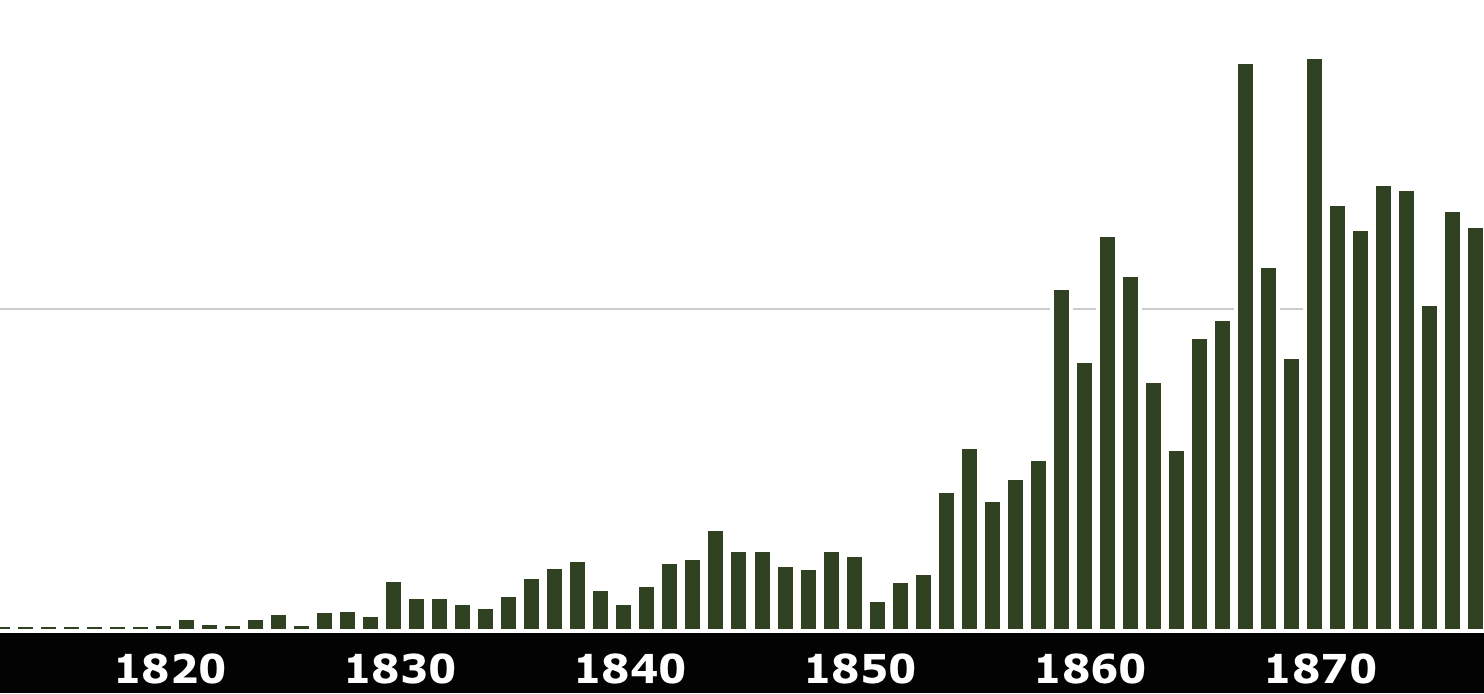

I began this answer by suggesting that the fragmentary approach is in certain respects unavoidable, and the reason I think we have to say this is that you can look at a particular religious tradition ? you can look at the Presbyterian response to Darwin, for example, as David Livingstone has done ? and the response of Presbyterians in Belfast was not the same as their response in Edinburgh, which was not the same as their response in Princeton. So, local circumstances and local events can often influence how individuals react. In Belfast, for example, in 1874, John Tyndall, [a] well-known physicist, gave a presidential address before the British Association for the Advancement of Science in which he effectively allied the Darwinian theory with a rather sophisticated kind of materialism?but also with the thesis that over the course of history, the advance of scientific knowledge had actually displaced religious authority. So rather tendentiously ? notoriously ? he makes the claim that we, the scientists, shall wrest from theology the entire domain of cosmological theory. That kind of aggressive line taken by some of the Darwinians ? by no means all, of course ? but taken by some, tended to elicit a negative reaction whenever it was perpetrated.

So, events of that kind can actually colour receptivity to the Darwinian theory. We now have wide ranging studies of the reception in New Zealand, the reception in the southern USA, the reception among Anglican clergymen in England? and in truth, it's the diversity that really is striking. In the Anglican case, for example, we've all heard of the Wilberforce/Huxley debate in Oxford in 1860, and that has tended to engender the notion that the Church of England was uniformly opposed to the Darwinian theory. In truth, one of the sermons that was preached during that meeting of the British Association came from one of Wilberforce's ordinands, Frederick Temple, who later became Archbishop of Canterbury. And it's clear from that sermon in 1860 ? summer of 1860 ? that Temple was really quite open to the idea of the extension of naturalistic explanation that one finds in the Darwinian theory.

So, whichever tradition you look at, I think you will find examples of those who were willing to be forward-looking, and examples, of course, of ultra-conservatives who felt that science in the shape of Darwin was actually destructive of the faith.

5. Darwinism among liberal Anglicans

Dr White:

I'd just like to follow up on that a bit more. Darwin had a number of clerical correspondents, and some were leading Anglican reformers and liberal theologians ? Charles Kingsley

was one, Frederick Farrar was another ? and we know that Emma and Charles both read works of liberal theology in the 1840s, especially works that adopted a historical approach to the gospels. And so, in spite of what you've just said, I'm wondering if it's possible to say that Darwinism was particularly appealing to liberal Anglicans. We do seem to find an extraordinary openness ? or attempt ? amongst some to take on board scientific approaches and scientific theories, to refashion Anglicanism. So, I'm just wondering if that's a fair assessment.

Prof. Brooke: Oh yes. In spite of what I have just said, I would certainly say, if we're taking a very broad view, then the more liberal Anglicans would have been more receptive; to the idea of evolution in particular. But I think we do have to differentiate here between the idea of evolution as a general thesis about where human beings have come from and whether the Earth has always been the same or whether it has had a very interesting history, both through nature and through human interactions with nature.

I'm rather inclined, I think, to say that when it comes to the specific mechanism of natural selection, not all of those liberal Anglicans who warm to the idea of general evolutionary progress were necessarily so receptive towards Darwinism in the rather more technical sense of being receptive to the idea that natural selection, working on random variations, could actually account for the history of life. And so, I think what we find among the liberal theologians is a willingness, as it were, to be fellow travellers with Darwin ? a willingness to see the world as the product of evolutionary processes; to see in those processes evidence of progress ? and I think that liberal theologians liked that idea of progress because they could argue that through the scriptures and right up to their own time there had been, as it were, a progressively more refined understanding of the nature of God. And that process of cultural refinement they could, as it were, tack on as the last stage of human evolution.

So, ideas of human evolution in general ? and the sense in which Darwin, of course, reinforced them ? all that, I think, is very appealing to liberal Anglicans. Having said that, I'm looking back now to a book that was published by James Moore in the late 1970s called The post-Darwinian controversies, where Jim argued with some cogency that some of these liberal interpreters of the Darwinian theory actually failed to come to terms with the science that lay behind it: it was in certain respects too facile an integration and a synthesis. And Jim argued in that book that it was the more conservative theologians ? those brought up, shall we say, within a Calvinist framework ? who were probably better equipped to appreciate the full force of the Darwinian theory ? and also, in certain respects, to respond to it. It's quite a difficult argument and I won't actually pursue it here other than to say that if you had been a Calvinist, you would have been concerned with problems like: how do we reconcile divine predeterminism, predestination, with human freedom? It's a philosophical and theological dilemma, and it's exactly that kind of dilemma that Darwin finds engaging, enthralling, but also ultimately irresolvable. So, there are certain patterns I think you can see between Darwin's thinking about freedom and determinism, and ways in which conservative theologians might also want to talk about those questions.

So, I hope that gives a plausible response, but it's a difficult question and it's made all the more difficult, I think, by virtue of the fact that if we say that the liberal Anglicans or certain of them failed to come to terms with the Darwin mechanism ? correctly formulated ? we have the ulterior problem that what Darwinism was, even in the last forty years of the 19th century, was not always transparently clear, because within the scientific community itself, there were debates about the sufficiency of natural selection. So if we say, well, actually a lot of these liberal Anglicans didn't really understand exactly what Darwin had said or didn't know quite how much weight to attach to natural selection, in a sense that reflects the wider problem that the scientific community itself was having over how much weight one should place on natural selection as distinct from other evolutionary mechanisms. And the irony, of course, is that from the first to the sixth edition of the Origin of Species, Darwin himself retreats somewhat over the weight to be attached to natural selection.

6. Evolution, emotions and the basis of faith

Dr White:

Another feature of some liberal Anglicanism in Darwin's day was a particular emphasis on the emotions as a basis of faith. There is an increasing turn in some liberal Anglican theology away from institutional, doctrinal or scriptural authority toward such emotional foundations: religious instincts, temperaments, strong feelings of devotion and obligation toward a higher being, or a sense of ultimate purpose. Emma Darwin's faith seems to be based largely on such emotional ground. But Darwin's later work ? in Descent of Man ? where he develops evolutionary explanations for human mental and emotional life? this would seem to call of this into question. He compares religious devotion to that shown by a dog for its master; belief in the supernatural to the fear displayed by monkeys. He writes about this in a letter in 1881 to William Graham: Would any one trust in the convictions of a monkey's mind, if there are any convictions in such a mind? Were such evolutionary explanations for religion itself ? and especially these religious feelings ? were these addressed in theology? We know that they gave Emma considerable discomfort.

Prof. Brooke: You've put your finger there, Paul, on an aspect of the agnosticism we associate with Darwin himself late in life, where he does, indeed, mistrust the power of the human mind satisfactorily to address the really big questions about the origins and purpose of the universe. Those big, metaphysical questions, he thinks the theologians of the past have been far too arrogant about in imagining that they can actually offer some kind of solution, some kind of explanation for the way the world is. It's also perfectly true, as you say, that Emma experienced considerable discomfort, and indeed has certain passages in the first draft of Darwin's autobiography deleted because she felt that this would, in a sense, by the very strength of language Darwin had used, misrepresent what she liked to convey to the public as a more sympathetic attitude towards religion on his part. So we are at the heart, here, of some very sensitive issues between Emma and Charles himself.

You ask, were such evolutionary explanations for religion ? especially religious feelings ? addressed in theology. It's not easy to answer that question because quite a lot of research done on specifically theological responses to Darwin ? and particularly on the interpretation of scripture after Darwin ? those studies tend to show that the Darwinian impact was perhaps not as great as we might imagine it to have been, and that these issues were not so widely discussed. So, I do actually find that quite a difficult question to answer.

It was of major significance for Darwin himself, and for Emma, and it's very striking that those who today are looking for an evolutionary account of the origins of religious belief do still find in Darwin himself all kinds of inspiration. As you implied in the introduction to that question, he observes that his dog once responded to the waving of a parasol in the breeze by barking almost as if it were recognising some kind of invisible intruder, and Darwin speculates that the origins of belief in some kind of invisible, supernatural agency, among humans, could well have been along those lines. So, there are very suggestive thoughts here in the Darwinian corpus itself, but I'm far from clear that theologians themselves were happy to take up these suggestions.

7. Is Darwinism part of a trend of secularization?

Dr White:

Darwinism is often identified with a wider movement of secularization in the 19th and 20th centuries, and many scholars have argued for a profound shift of authority from traditional religious institutions to science. Do you think this is an accurate picture? Do you think that we must understand Darwin's work and its reception as part of a larger process of secularization, especially in light of more recent developments, such as the resurgence of fundamentalism?

Prof. Brooke: The concept of secularization is a very slippery one, and the relationship between scientific advance and secularization is perhaps even more complicated. I say this because if you look for a dictionary definition of secularization, it will say something like, A concern for things of this world as opposed to the church. That's the Oxford English Dictionary definition of secularization. The problem is, by definition, any form of science, because it's concerned with an investigation into the workings of this world, becomes automatically secular. That doesn't seem a very satisfactory way of handling this problem because, of course, many great scientists of the past ? and there are still some today who ? are religious believers, often of a very pious kind. So, to present science as somehow intrinsically secular, almost necessarily so by definition, I think is not a particularly helpful way of approaching this question.

Now, of course, it's very plausible to suggest that what Darwin does it almost complete (I think one has to say almost complete): a process whereby science itself becomes secularized in the sense that scientific texts after Darwin very rarely make reference to any kind of supernatural involvement with the natural order. [I] can't quite say that was true of Darwin himself, because there are oblique ? and occasionally explicit ? references, even in the Origin of Species, to some kind of breathing of life into the first primordial forms, or indeed in setting up the laws of nature so that human beings would eventually evolve. So, there are ways of looking at the Origin of Species which would not necessarily turn it into a secularizing work, but having said that, the fact that Darwin could give an explanation for the appearance of new living forms without having to postulate any form of divine intervention, that I think did contribute to, shall we say, the plausibility of a secular, a materialist, an atheistic even, view of the world if you were predisposed to take that view. And there's no doubt Darwin's theory is a very powerful resource for secular thinkers, who do use it to suggest religion has had its day and that the clerical responses to Darwin's theory are the sort of last vestige of a fight between science and religion that the church was ultimately bound to lose.

We have sometimes thought of secularization as the separation of science from the authority of religion, but lots of scholars have written as if one of the more potent forms of secularization is not when there's separation of science from religion but when there's actually a kind of fusion where religious doctrines are reinterpreted in the light of new forms of science. And this clearly did happen in the wake of the Darwinian contribution, because religious thinkers began to see God's participation in a creative process that was continuous rather than something that had been a one-off in the dim past. So, we actually have a problem here, which is that the word secularization is used both to refer to the separation of science from religion and also to the reinterpretation of religion when there's some kind of fusion with science. So, I do think this is actually a very tricky question to get one's head round.

The critical issue, I think, is whether the science itself can still be interpreted in ways that make sense to religious people and which are not seen to completely jeopardise the central doctrines of a faith tradition. And on that particular point, the views have been sharply divided, I think, within the Christian church. But it's worth pointing out, I think, that there were theologians ? certainly at the end of the 19th century ? who were willing to see in Darwin's work a reinforcement of certain doctrines that they thought had perhaps rather faded from view and needed to be brought back into the light.

I'm thinking of a group of theologians here in Britain who reaffirmed the centrality of the doctrine of the incarnation in Christian thought: that the presence of Christ in the world as the Son of the Father was a very profound symbol of God's participation in the world rather than being some rather remote figure who just intervened every now and again to create a rhinoceros or a flea, or something of that kind. This participation in nature was certainly emphasised by many theologians who felt that the semi-theistic picture of the God who just simply intervenes every now and again was actually a travesty of the Christian tradition where providence was supposed to be intimately involved in the affairs of nature.

So you have the very striking statement by Aubrey Moore ? which has often been noted ? where he writes that under the guise of a foe, Darwin has done the work of a friend. And what he means by that is that Darwin has liberated Christianity from rather naive, superstitious images of divine intervention and replaced it with a much more intimate image of God's creative and redemptive participation in the natural order.

8. Darwinism as part of a religion of science

Dr White:

One alternative to this secularization interpretation might be to view this newly acquired authority of science in the second half of the 19th century as actually analogous to religious authority. It's curious, for example, how Darwin uses the conversion motif when discussing people who have adopted his theory. And Darwin himself becomes a cult figure or quasi-religious authority for a wide spectrum of people and movements. So, we're talking about very heterodox believers here: not Christians per se. One example is the botanist Francis Boott, who writes to Darwin in 1860, I have a profound reverence for Abraham & Moses & Jesus Christ, & I have much of the same reverence for you, whom I look upon as the High priest of nature. But the Church would condemn me to the stake for my religious creed. So, if Darwinism isn't part of a movement of secularization, is it then perhaps a kind of new religion?

Prof. Brooke: I think it's often been said that the Victorians found a new religion, and that religion was the religion of progress. And insofar as the Darwinian theory could, as it were, play a part in sustaining that image of progress, then one would have to say that it was contributing to an alternative form of religion.

As you say, it is interesting how Darwin uses the conversion motif when talking about those who've adopted his theory, and I've often reflected on this. Of course, in a way, it points to something very profound, that many Darwinians in subsequent years have commented on. There can be a kind of existential experience when you first fully look at the world through Darwinian spectacles. It often happens to youngsters in adolescence, I think, when they first see an alternative to the notion that living things have been designed for their particular niche in Creation, and when they see for the first time that the Darwinian theory gives you a vision of a massive extent of extinction in the history of the world: that when we look at the creatures trotting around today, they are the survivors of this long, bloodstained tortuous trail of evolution. It can be an existential experience because it's a kind of gestalt switch: you suddenly see the world in another way. And the Darwinian theory has had that impact on a lot of individuals.

One of the first examples was the naturalist Alfred Newton, who became a Darwinian convert almost immediately, and he describes the process how having read the papers of Wallace and Darwin ? I think these were actually the 1858 papers presented at the Linnean Society ? having read those, he went to bed one night and woke up the following morning as if, suddenly, he could see the light. Natural selection was the answer to all the problems he'd been plagued by in his biological research.

Now, the fact that it's possible to have existential experiences seems to me to explain really quite a lot. It also helps us to understand why Darwin himself said, that unless one has been staggered by the theory, one hasn't understood it. And quite a lot of the religious thinkers we've been reflecting on, I think were not staggered. They didn't quite see the drama that lay behind this kind of switch. So, to use a word like conversion, in a way, does capture something. It may not mean conversion from one religious position to another religious position, but I think it can mean a kind of conversion to a quite different paradigm: to a quite different way of looking at the world. And that's why, of course, Darwinism was a resource for those who wished to construct arguments as part of a critique of religion. Whether Darwinism could then be said to constitute a kind of secular religion, well, I think there are cases where new philosophies of science became religions in the 19th century. There's a very striking example in the philosophy of August Comte, who might just have influenced Darwin slightly through his image of a human history in which there had originally been a theological response to nature, then a more metaphysical approach to science, and then finally the positive age, which, for Comte, implied the rejection, certainly, of Roman Catholicism; a rejection of the religious in favour of the science. But the fascinating thing, as I think Huxley once said, is that Comte gives us, as it were, Catholicism minus Christianity. Comte's Positivist philosophy did turn into a kind of religion: there were Positivist churches, there were even prayers said in Positivst churches. Christmas was celebrated perhaps more as it might have been in Pagan times: the Christmas tree became the symbol of this Positivist Church. It even had its saints, and the saints were very largely composed of French scientists. So, the notion that science can get transformed ? or a science-based philosophy can get transformed ? into a secular religion isn't a far-fetched idea. And it's sometimes said that those today who would say that science is the only way of gaining any kind of knowledge or understanding of the world are being scientistic rather than scientific, in the sense that they are making this very strong claim that no information, insight, wisdom, can come from any source other than science. And if you take that view, it can quite easily graduate into a kind of dogma which bears a certain resemblance to religious dogmas.

So, I do see the force of that question, certainly. Science, for some, does become a kind of surrogate religion, particularly if it completely dominates their life.

9. The rise of confrontation in science-religion debates

Dr White:

You have remarked in a lecture on the Huxley-Wilberforce debate that it was part of the tradition of the scientific gentleman in the early 19th century not to enter into religious controversy, and especially not to press one's heterodoxy onto others. And you refer to a letter from Joseph Hooker to Darwin in 1865 in which he notes the pain and grief that this would cause one's close relations ? and we know from Darwin's own writing that this was very much the case for him as well. Much later, in 1873, Darwin advises his son George against publishing views against Christianity, and he [Darwin] writes, The evils are giving pain to others, & injuring your own power & usefulness. And then he refers George to Lyell, of whom he says, Lyell is convinced that he more effectively criticized belief in the Flood by never having said a word against the Bible.

Well, I have a question, then, about this. Do you think this approach of avoiding controversy is one that is replaced over the course of the 19th century by a more aggressive stance ? one typified, say, by Thomas Huxley or Ernst Haeckel ? are these people more typical of the manner in which science and religion were debated in the 2nd half of the 19th century?

Prof. Brooke: It's absolutely correct, of course, to say that Darwin himself was very humble, very self-effacing in what he was prepared to say about the implications of his own science for religious belief. And I think there are lots of reasons for that, as we know. There were family reasons: he didn't wish to inflict pain on Emma and other members of the family. I think he does, also, genuinely believe that to attack religion explicitly and openly, by, for example, using scientific theory to call into question its dogmas, is going to be counterproductive. And, I have to say, I'm very sympathetic to that view myself. It seems to me, if you go on the offensive, you are very unlikely to influence those you most wish to influence, because their religion is probably conferring some special meaning, orientation, direction, purpose, to the lives of those who subscribe to that religion, actually in very deep ways, which the sciences can't always reach, it seems to me. And therefore, if you beat the drum of saying that the science is antagonistic to the religion and you've got, somehow, to make a choice between the two, the great danger, I think, is that those who subscribe to religious beliefs which as intellectuals we might perhaps want to call into question? the damage is that you actually reinforce that belief rather than undermine it. And I'm very saddened by what I see in the world today where fundamentalists on the religious side and extremely dogmatic scientists at the other end of the spectrum, seem to feed off each other in the sense that they launch attacks which simply have the effect of digging deeper those who wish to oppose them.

Now, the question you've asked is whether Darwin's stance was the more typical in the 19th century or whether we should look to Huxley and Haeckel and others as being more typical, where one gets a much more open attack on, well, on theology particularly; not always on religion, and this is a rather important distinction. It's an important distinction for Huxley, who actually says somewhere that the much-vaunted antagonism between science and religion is something of an artefact: the real antagonism is between scientific truth and theological dogma. And that antithesis is one that I think was taken up by quite a lot of commentators on these debates. It was certainly taken up by perhaps one of the historians who has done most to give the impression of an inherent conflict between science and religion over the centuries ? and I'm thinking of Andrew Dickson White's book A history of the warfare of science with theology in Christendom, which was published in the 1890s ? and the point that White made was that science is incompatible with the spirit of dogmatism that has often been present within academic theology, and within certain ecclesiastical traditions, of course. But even White wants to say that he doesn't think that science necessarily rules out religion in some more attenuated sense. If one focuses on the practice of religious belief or the kind of emotional sustenance that religion can give, or even that sense in which people look to the natural world and feel able to celebrate the wonder of Creation, as many earlier scientists were certainly able to do. Those kinds of responses to nature need not be obliterated by scientific advance.

So, I think we do have a very interesting question here, which is of immediate relevance today: which is the more effective strategy if you are wishing to attack a particular religious tradition. Do you go out-and-out to demolish it, or do you adopt the gently-gently, softly-softly approach that Darwin adopted in the conviction ? I mean, certainly in his

conviction ? that scientific knowledge and its advance would gradually have the effect in society of corroding certainly what he considered some of the more pernicious dogmas within the Christian religion? And there's no doubt he had very little sympathy by the middle, and certainly the later years of his life, for Christian doctrine as he had been exposed to it.

10. Is it useful to think of a boundary between science and religion?

Dr White:

So, let me just ask a final question, then, and I'd like to return to the subject of boundaries. You have written a highly influential book titled Science and Religion, with some historical perspectives, and you've been a Professor of Science and Religion at Oxford. You've also stated some years ago that the categories science and religion ? although they are often applied very broadly across space and time ? have in fact only emerged fairly recently. Can you say any more about when this boundary between science and religion was drawn, and why? And are these categories still useful today?

Prof. Brooke: I think when we're talking about science and religion, we're using two words which do act as, kind of, preliminaries. They act as crutches to enable us to get into a more serious discussion about: how nature should be interpreted; how we gain knowledge about nature; what kind of role religion plays in society. I think it's fairly clear that a word like science has a very long history. In fact, [it comes from] scientia, defining in the ancient world simply any organised and systematic body of knowledge, so for example theology itself could be called a science and was often claimed to be the queen of the sciences in that respect, meaning an organised body of knowledge. Interestingly, even in the late 19th century, Huxley refers to theology as a science, so despite his opposition to it? that use of language is still operative even at the end of the 19th century.

But of course, the word science then ? particularly, I think, through the great specialisation that occurred between the late 17th and the middle years of the 19th century ? came to carry rather different connotations and certainly still meant knowledge, or provisional knowledge of nature. Or probable knowledge of nature, and that was a rather interesting issue, because a technical definition of science ? scientia ? for many in the 17th century, would have included the notion that the knowledge was demonstrable: it was certain, it could be deduced in some way from axioms. What we know as modern science today, emerging out of what in the 17th century would have been called natural philosophy

? a branch of philosophy? knowledge for natural philosophers like Robert Boyle, for example ? even John Locke ? could not be demonstrative knowledge in that deductive sense. If you were trying, for example, to hypothesise about the arrangement of atoms that gave rise to certain chemical compounds and processes, you didn't have direct access to that hidden, microscopic world. You could conjure up your hypotheses, but they would only be, as it were, probable knowledge rather than being certain knowledge. So, there is in the beginnings of the modern period almost a tension between the demands for definitive knowledge which the use of the use of the word scientia would have normally carried, and yet the awareness that an experimental natural philosophy probably couldn't give you that definitive knowledge because the experimental were always liable to be consistent with more than one hypothesis. And that very issue, of course, is one that has been of great interest to philosophers of science ever since.

So, the word science is problematic. It's had a long history, a complicated history, and now it tends to have the connotations of hightly specialised knowledge grounded in research. But there's another problem even with that, which is that when we use the word science, as I say, it's a kind of approximation, but for a lot of people, the unification comes from the fact that science is supposed to depend upon a unique method, the scientific method, as it's often called, as if all forms of science followed exactly the same methodology. Now, this is another dreadful oversimplification.

Even as long ago as the 1830s, the very philosopher who invented the word scientist, William Whewell, made it perfectly clear that different forms of science have different methodological requirements! If you are doing a historical science like geology or evolutionary biology, you often do not have direct access to the very thing that you are talking about. You don't have direct access to the turning of one species into another thousands, thousands, millions of years ago. So, there are issues about even the propriety of talking about a unified scientific method. It belongs more to the discourse of the interaction, I think, between scientists and their publics. It's very important for scientists, of course, to be able to impress the public with the power and the authority that lies behind the claims they wish to make ? and to celebrate a unique scientific method is one way in which you can engage the public's attention with that. But all this, I think, adds up to saying that that one word, science, is insufficient for describing a plethora of activities that scientists actually get up to. So, we can [say], as many sociologists, I think, have said: science is what scientists do ? as well as, as it were, conforming to some idealised method.

Now, your question also involved the word religion, and that, I think, also has an extremely interesting history, for a very simple reason. If you in earlier periods subscribed to a religion ? let's take the Christian faith as an example ? you would tend, I think, to see other forms of what we would now call religious belief in terms of your own religion. So, for example, you would be liable to see Jews, and the representatives of Islam, pagans from the past? you would tend to interpret them through the eyes of your Christianity: they were, in short, heretics of various kinds. But the more over the years there was an encounter with so many other cultures ? including the Chinese, and native American cultures, of course ? the gradual accumulation of the encounter between Christianity and other cultures creates a situation where eventually you are more or less forced to acknowledge that there are other cultures which have their own sets of beliefs and which, if you wish to analyse at all empathetically or sympathetically, have to be regarded as somehow having a comparable status to one's own religious tradition. Now, by comparable, I don't mean as true as, because there would, I think, have been a lingering suspicion ? as there still is today within specific religious traditions ? that those outside are somehow subscribing to false deities. But I think by the end of the 17th century, as you move into the 18th century, there is an awareness that if you're going to analyse other cultures, it may be helpful to have this word religion, that enables one to specify what are the beliefs of those alternative cultures. And I think this is how the word religion has come down to us from that period, today.

But it's striking there are still throwbacks to that older kind of perception that I mentioned earlier. I mean, I have sometimes heard people say Christianity is not a religion. And I've heard that same sort of statement made by muslims and by others, because the moment you say Christianity is a religion, there is a sense in which you have ? I won't say deconsecrated it, but you have turned it into the subject of academic inquiry.

So, that's a very sketchy answer to a very, very complicated issue, but you asked where and when a boundary between science and religion was drawn. I think my answer to that has to be that there is no one place, and no one time when you can suddenly say: in that text, you can detect a very clear demarcation. And it's a complicated question, because you could take a figure like Isaac Newton, for whom many people, I think? he would be a kind of paradigm case. Now, there are respects in which Newton makes a sharp differentiation between natural philosophy and religion ? and he does use the word religion in that way. And the task of theology and the task of the religious exegete of scripture, for Newton it's a very different task from that of the natural philosopher who is interpreting the natural world. But, interestingly, it's not an absolute boundary, because we know that Newton, for example, believes that the solar system is not always going to be, as it were, eternally stable. There are interfering factors, and he suggests that God has a role in stabilising the solar system every now and again: there's some kind of divine initiative in interactions with nature. There's even evidence that Newton regards gravity as ? possibly at least ? the direct action of God in the world. He's not always clear on that; he's got three or four different accounts of what gravitation may or may not be? but the point I'm making is that in Newton, you have somebody whose science ? the celestial dynamics and his analysis of the solar system ? in that work we have something that we would be very happy to call science, and yet he calls it natural philosophy, and he says it's part of the business of natural philosophy to talk about God and his relationship to the world. So boundaries are drawn ? they're drawn by Newton ? but there is a sense in which the boundaries are still permeable. And I think they remain so right up to the time that Darwin was working, and in popular scientific literature for long afterwards there's a sense in which on certain levels, you could fix a sharp boundary between the realm of religion and the realm of science. But on other levels, there remains that permeability.

An example that I often use, taking us right back to Francis Bacon, who's often seen as the, kind of, father of the scientific method, and a great visionary in terms of the power we can gain from studying the natural world? Bacon is often celebrated as the secular thinker who says that scientific and religious explorations and explanations should be kept segregated. If you're asked the question, Why is it raining outside? you shouldn't reply, Because it's God's will.: there will be an explanation in terms of meteorology. And Bacon is very clear you shouldn't conflate those kinds of explanation. But at the same time, on other levels, the boundaries are very permeable, because he suggests that science itself is a profoundly religious activity: it's a duty we have to explore the book of God's works, just as there's a duty to explore the book of God's words.

So, I prefer to think not in terms of some kind of vertical curtain that comes down between science on the one side and religion on the other. I prefer, actually, to look at it, as it were, horizontally, on lots of different levels, and to see how there may well have been a contraction of space for interaction between the two on certain levels. But on others, such as Why should science be pursued at all? ? when you start asking value questions of that kind ? then I think you can still find that permeability. So, yes, the categories are still useful, but they have a very complicated history, and I think we should recognise that the words science and religion do function as crutches in this kind of debate. And we should much rather talk about sciences and religions than this monolithic thing called science

and this monolithic thing called religion, because they're not things: they're practises, they're what people do.

Dr White:

Well, that's a very nice way to end. Thanks so much, John.

Prof. Brooke: Well, it's been a great pleasure, Paul.