From M. B. Bathoe 25 March [1871]1

Descent of Man

Vol 1. Chap 1. Page 21

“But I have never heard of a man who possessed the least power of erecting his ears”.

On this point enquiry might be made in the United States—for my mother—Mrs. Hume remembers often to have heard from her father Mr. Burnley that in his youth he had seen Red Indians who when listening attentively erected the outer ear; curving it up as one sometimes sees a European do by aid of his hand. I personally remember the same having been told me by my grandmother Mrs. Burnley:2 & I think she named the tribe to which they belonged—but it was not retained by my childish memory & my mother (now 84 years of age) can recall nothing beyond the bare fact—

Mr. Burnley was a land owner on the James river near Norfolk in Virginia: & had travelled repeatedly towards the Missisippi thro’ country then mostly unsettled, which has since become Kentucky & Tennessee—also in the Carolinas— But he quitted America, never to return, on the declaration of independence in 1776—having passed some previous years in arms on the Royalist side: so his observations must date a century back—

Vol 1. Chap 2. Page 46 & 7—

Two or three cases of Reasoning in animals that have fallen under my observation seem to me curious— if not really worth notice the paper can easily be thrown into the fire—

In 1845 I had a pet Antelope at Panneeput (30 miles North of Dehlie)3 I had brought it up from a few days old & it was quite at liberty & used to run about the country: but chiefly spent its time in our grounds & always came at sundown to be fed in a half unroofed mud outhouse where it had been kept in infancy & where it was locked up every night to protect it from jackals— I may say locked up with its own consent: for it always walked in voluntarily & never attempted to run out when we closed the door— It would follow me about like a dog & when it attained maturity its affection was more demonstrative than agreeable, as I was often nearly knocked down & once considerably hurt by its bounding upon me— in 1846 we removed to Kurnaul4 30 or 40 miles further N.W—& at first the Antelope was kept tethered, then carefully watched till it appeared quite at home in the new home— However one day he disappeared & the next day my husband (who was Magistrate & Collector) received a report from one of his native officers at Paneeput, that my Antelope, well-known by its scarlet leather collar, had returned at sundown to the Paneeput grounds, walked into the outhouse as usual, there been captured & would be sent back to me.— Exactly the same occurred a second time: after which I kept him much longer tethered & under surveillance & really thought he was quite reconciled to the change—but—again he went off, but not to the Paneeput grounds: which he was never known to re-enter, altho’ he was several times seen in the vicinity & altho’ every effort was made to entice him back again—

Now was not that reasoning?

“I wish to remain near Paneeput—but if I go into those grounds I find that I somehow get removed to Kurnaul—therefore—I will not re-enter those grounds tho’ formerly my most favorite haunt”—

In 1850–51 at Meerut 30 miles NE of Dehli, I had a Hog deer, similarly brought up from infancy & similarly running quite loose—5 Unlike the Antelope however it seldom if ever went out of the grounds, & instead of being shut up at night it lay on its own mat under a portico before which a native sentry paced— It liked to be patted & noticed by us: & it distinctly recognized persons who were much about the house—but its affection was chiefly given to the 4 or 5 men who took turns as sentry (NB Its evening meal was given under this same portico)

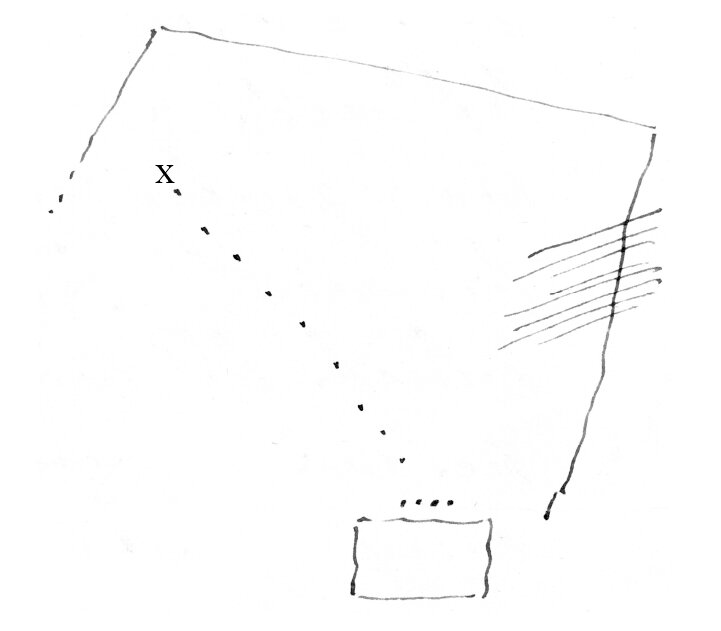

One day I heard an outcry of “The hunt is coming thro’ the grounds” & in alarm for my hog deer ran to the portico— He had been at the x when the hunt came over the wall at

One day I heard an outcry of “The hunt is coming thro’ the grounds” & in alarm for my hog deer ran to the portico— He had been at the x when the hunt came over the wall at

& instead of running away as would have seemed natural, he rushed across its course by the dotted line (very narrowly escaping the foremost dogs) to the sentry under the portico—& no farther—but putting his muzzle in the man’s hand stood firm while some of the dogs swerved round towards him— When I knelt down & put my arms round him as a protection & encouragement (while the servants kept off the dogs) he was trembling like an aspen leaf & watching the movements of the dogs in evident terror—but he never attempted to run away from them any farther, nor ever moved his muzzle from the hand of the sentry—

& instead of running away as would have seemed natural, he rushed across its course by the dotted line (very narrowly escaping the foremost dogs) to the sentry under the portico—& no farther—but putting his muzzle in the man’s hand stood firm while some of the dogs swerved round towards him— When I knelt down & put my arms round him as a protection & encouragement (while the servants kept off the dogs) he was trembling like an aspen leaf & watching the movements of the dogs in evident terror—but he never attempted to run away from them any farther, nor ever moved his muzzle from the hand of the sentry—

Must it not have been some process of reasoning that taught him to seek the protection of his human friend & comrade? altho’ in so doing he actually had to meet the cause of his alarm—

Experience could have no influence: as the only dogs he knew had grown up with him & never molested him: he had never before seen a pack of hounds— Nei- are hog deer (in that country at least) ever hunted—as they frequent broken ground covered with brush wood & grasses 6 feet high where riding would be impossible, at any speed—

About this same time & at the same place I had a pet Mongoose: of the small-variety well known (in India) for their susceptibility to domestication:6 & their habits of extreme personal familiarity— Two were brought to me when 2 or 3 days old: & they were extremely troublesome as long as they required milk-feeding: for they very early possessed little sharp teeth which they employed much more freely than was at all agreeable— After being kept in a box at first, then tethered to a table & afterwards kept loose in an unused room, they were left free to run about the house which they kept quite clear of snakes & other vermin— For some months they never were known to quit the house: but, one never became so tame as the other: that is, it seldom came near us save at feeding time, & tho’ it wld. obey a call & allow itself to be handled it did not court such notice— Both markedly preferred my husband & myself to any natives—even the servants who assisted in feeding them— indeed they would peep into his business room & if the native clerks & attendants were there in numbers would immediately retire; altho’ they ran about there as freely as in any other room out of office hours— (this may have been smell).

When we were absent for some months in camp they apparently less liked their home—& on our return we found they were a great deal in the garden (where were plenty of their fellow-creatures) only coming into the house for food—& one soon ran wild altogether— The other remained perfectly familiar—would play about us the prettiest tricks, especially a kind of hide & seek, delighting in a chase—or it would run up onto our laps: hide in his loose sleeves, or behind his waistcoat—or run over my shoulder & drop down on my lap rolling on its back & inviting play & tickling like a kitten— It no longer used its teeth so as to give pain, but would seize a finger in its mouth & mumble it by way of caress: & the only mischief it ever did, was to the muslin frills & lace trimmings of my dresses: which it would tear into ribbons with its teeth while holding them down with its paws.

So far I believe it only resembled many others of its species who are often kept as pets especially by young men—

But one of its habits was I believe unique— After it frequented the garden it no longer required regular feeding: sometimes it got nothing from us for days together, still running about the house & playing with us as usual—but when it was hungry it wld. come straight up to the sofa where I (being in ill health) was generally lying & stand up on its hind legs to beg like a dog—wh: we certainly never taught it to do— Often I tried the effect of not noticing the entreaty— It would then run up onto me, & in some way or other attract my attention, which being accomplished it would suddenly leap (not run) on to the ground & again stand up to beg— When however I rose from the sofa it did not follow me, but raced away (losing sight of me meanwhile) straight to a side table in the dining room, where under a heavy cover was a dish with shreds of meat always ready— Here I would find it waiting & however slowly I might move, it waited quite patiently so long as I continued moving but if after reaching the table I delayed more than a reasonable time in beginning to feed it, up went the little animal again in the begging posture: & once when I intentionally delayed a long time, it somehow scrambled up the skirt of my dress on to the table & there set itself up under my eyes—

Could it more distinctly say, I am hungry— attend to me—

I never knew it thus beg without being ready to eat whatever I would give—tho’ it often refused food that I offered at other times—& altho’ its subsequent proceedings showed how well it was aware of the locus of the food, it never went there till after it had secured my presence: which surely exhibits a connexion of ideas not distinguishable from reasoning—

We left the place suddenly from severe illness & had no means of taking our little pet who soon ran wild again I dare say.

In no one of these cases can the principles of heredity, account for any of this mental cultivation— all were the offspring of perfectly wild parents (& grandparents ad infinitum) who had never been domesticated or perhaps seen a human being—so the circumstances in which they were placed were totally novel—

Vol 1. Chap IV— Page 142. note— “Dr. Bachner xx has given good cases of the use of the foot as a prehensile organ by man”:7

Do these include the carpenters & tailors of Upper India who habitually hold one end of a long piece of wood, or a long seam on which they are working between the great toe & its next neighbour— indeed I have seen one of my native maids, pick up a light thing from the ground with her foot instead of stooping for it: but she may have been an exception as I cannot remember to have seen any other person do so— None of these people were ethnologically of low classes—not of any of the aboriginal tribes, nor the black Tamul races—but of the true Aryan race, delicately formed, with black eyes, long straight black hair & skin a light mahagony color: low-cast Hindoos—

Pray do invent some name for our remote predecessors— Some sonorous but not difficult word of classical derivation (like Hipparion)8

You are writing for the general public, with whom there is a great deal in a Name (begging the poet’s pardon)9 & the unpleasant, as well as awkward phrase “the ape-like progenitors of Man” excites a very unnecessary degree of prejudice against the System.—

As the facts above stated rest on my personal testimony I feel it needful to sign my name, altho’ perfectly aware that it possesses no weight social or scientific—

Maria Burnley Bathoe

6 Bryanston Sq— March 25—

CD annotations

Footnotes

Bibliography

Descent: The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. By Charles Darwin. 2 vols. London: John Murray. 1871.

EB: The Encyclopædia Britannica. A dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information. 11th edition. 29 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1910–11.

Freeman, Richard Broke. 1977. The works of Charles Darwin: an annotated bibliographical handlist. 2d edition. Folkestone, Kent: William Dawson & Sons. Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, Shoe String Press.

Summary

Anecdotal comments on various sections of Descent:

Red Indians erecting their ears;

reasoning in a pet antelope, stag deer, and mongoose;

use of foot as prehensile organ by carpenters in India.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-7624

- From

- Maria Burnley Hume/Maria Burnley Gubbins/Maria Burnley Bathoe

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- London, Bryanston Square, 6

- Source of text

- DAR 87: 31–6

- Physical description

- ALS 10pp †

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 7624,” accessed on 26 November 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-7624.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 19