From Jeffries Wyman 11 January 1866

Cambridge [Massachusetts]

Jan. 11th. 1866

Dear Sir

Having lately given some attention to the study of the cells of the bee I have been struck with the fact that the deviations from the form alledged to have been measured by Maraldi & which was calculated by Koenig, are much greater than is mentioned in any of the descriptions I have seen.1 The conclusion to which I have been led, is, that whatever the typical form of the cell be, it is rarely, if ever, realised.2 As you have given your own careful attention to this subject, I feel that I run the risk of writing what may be already better known to you than to myself.3 Then it occurs to me that cumulative evidence is worth something. At all events I will state what I have to say briefly.

1st After repeated measurments of hundreds of worker cells I find, as Reaumer did in the drone cells, that the diameters are very frequently variable, so that nine cells measured in the direction of one diameter will sometimes fill a space, which it will require ten to fill if measured in the direction of another.4 2d. The terminal rhombs are the most variable parts of the cell. I have shown this very satisfactorily by means of plaster casts, & even by the coccoons from old brood cells which give a very good model of the base— Sometimes the rhombs are all of different sizes, & at others one is nearly eliminated, the other two making nearly the whole of the partition between two adjoining cells. 3d. The introduction of the fourth side to the base does not always, or even generally depend upon the transition from worker to drone cells, as stated by Huber,5 but either upon an incorrect allinement of the cells on opposite sides of the comb, or upon an increase of the size of the cells on one side not corresponding with that on the other. 4th the most remarkable deviation which I have noticed is a sort of rotation as it were of the cells, so that those of the two sides, differed in position about 30o.

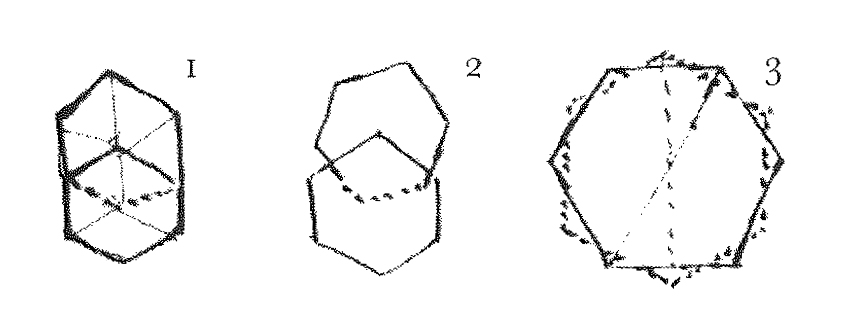

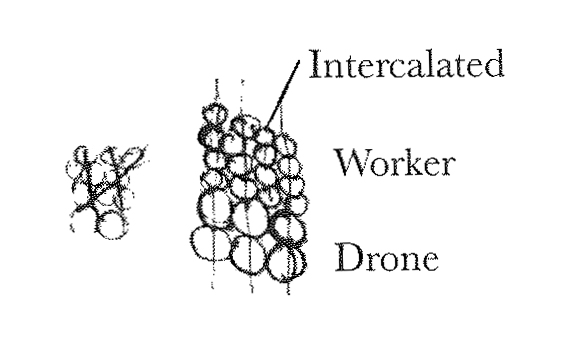

Fig 1 being the normal position, 2 & 3 are the abnormal ones— in 2 the angle of one cell corresponds with the centre of the other, but instead of pointing to one of the angles of the other cell it points to one of the sides. In 3 the cells were fitted together by their whole bases, &, projected on to the same plane, are concentric. In both of these cases the rhombic faces became impracticable, & the bees compromised on a flat bottom to the cell— I found this arrangement in a large part of a worker brood-comb, & in the whole of a piece of drone comb. 5th. Lastly there is no regular mode of transition from worker to drone cells, but this may be effected in several ways, viz by means of irregular polygonal cells, by a gradual change of size, so that no line of separation is noticeable between the two kinds; & by the close approximation of worker & drone cells making an abrupt change; but as the worker cells are one fifth smaller than the drone cells, & therefore fail to fill up the space, a new row is intercalated for this purpose.

These intercalated rows however do come at regular intervals, & the emergency is often met by thickened walls.

I have studied the cells with reference to the hexagonal shape, & it seems to me that the view taken by Mr Waterhouse & yourself is the most tenable one.6 Fearing that you may not have seen the work, I take the liberty of calling your attention to the so called “fossil tadpole nests”, in Prof Hitchcocks report on the Ichnology of Massachusetts. Have you not there exactly the phenomenon in question? A lot of tadpoles get together each wiggling about on a centre, as is is necessary in a crowd, each excavates a place in the mud, but their respective cavities soon come in collision & a flat wall between them results, & in many cases a hexagonal cell almost as true as that of the bee—7

One thing seems entirely clear, that the hexagonal cell results from the cooperation of several bees & is never made by a single bee, & if he have no antagonist in the construction of a wall it is curvilinear.8 In some of my wasps nests from S America it appears that even in working with paste board, the outer walls of the new cells are always curved at first, but when other cells are made outside of them they are flattened so as to conform to those that have preceded them.

Before I close allow me to mention the observations of Mr Putnam on the cells of our humble bees—which he has shown are at first a mass of pollen & honey, on which an egg is placed, & into which the larva eats as soon as hatched.9 The cavity thus formed is the beginning of the cell.— This is increased by additions of pollen, which is gradually consumed; eventually wax is applied to the exterior in a very thin layer.10 I requested Mr Putnam to send you a copy of his paper, which perhaps you will have received before this reaches you.

I fear I have trespassed upon your time, but hope you will excuse me on the score of good intention

With great respect | Truly yours | J. Wyman

Charles Darwin, Esq. | Downe Bromley Kent.

CD annotations

Footnotes

Bibliography

Correspondence: The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt et al. 29 vols to date. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985–.

Hitchcock, Edward. 1858. Ichnology of New England. A report on the sandstone of the Connecticut valley, especially its fossil footmarks, made to the government of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Boston: William White.

Huber, François. 1814. Nouvelles observations sur les abeilles. 2d edition. 2 vols. Paris and Geneva: J. J. Paschoud.

Koenig, Johann Samuel. 1739. Lettre de Monsieur Koenig à Monsieur A. B., écrite de Paris à Berne le 29 novembre 1739 sur la construction des alvéoles des abeilles, avec quelques particularités littéraires. Journal helvétique, April 17 40.

Maraldi, Giacomo Filippo. 1712. Observations sur les abeilles. Mémoires de l’Académie Royale des Sciences (1712): 297–331.

Marginalia: Charles Darwin’s marginalia. Edited by Mario A. Di Gregorio with the assistance of Nicholas W. Gill. Vol. 1. New York and London: Garland Publishing. 1990.

Origin 4th ed.: On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. 4th edition, with additions and corrections. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1866.

Origin: On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1859.

Prete, Frederick R. 1990. The conundrum of the honey bees: one impediment to the publication of Darwin’s theory. Journal of the History of Biology 23: 271–90.

Réaumur, René Antoine Ferchault de. 1734–42. Memoires pour servir à l’histoire des insectes. 6 vols. Paris: Imprimerie royale.

Seeley, Thomas D. 1995. The wisdom of the hive: the social physiology of honey bee colonies. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: Harvard University Press.

Stanek, V. J. 1969. The pictorial encyclopedia of insects. London, New York, Sydney, Toronto: Paul Hamlyn.

[Waterhouse, George Robert.] 1835. Bee. In The penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, edited by Charles Knight, vol. 4, pp. 149–56. London: Charles Knight.

Summary

Has made observations on bees’ cells. Their dimensions are not constant, nor do single bees make single cells; each one is a result of co-operation.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-4974

- From

- Jeffries Wyman

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- Cambridge, Mass.

- Source of text

- DAR 181: 191

- Physical description

- ALS 6pp

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 4974,” accessed on 21 November 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-4974.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 14