From George Robert Waterhouse 10 February 1858

British Museum

Feb. 10. 58

My dear Darwin

I am sorry to see by the Date of your letter, it is some days old, & has not been answered—1 ‘till now I have not had time to examine the nest & report upon the same—2 But first let me speak of the Osmia atricapilla— I regret much to have set you on a wild goose chase—I have published my paper & was, as I imagined, pretty certain that it was printed in the Penny Cyclopedia—I must endeavour to find out where it is—3 in the mean time I can tell you the chief points— I saw a specimen of this same Osmia flying heavily with a mass of something held by its legs, somehow, & I watched the insect fly down to a grassy, steep, bank by the side of the River at Liverpool—the insect disappeared in the grass but I layed myself down & by parting the grass gently caught sight of the Osmia which I soon had the pleasure of seeing at work—the pellet was of clay or mud which was deposited in a small cavity in the soil & a portion of a cell was formed by the insect excavating in the mud a small circular cavity working with her jaws ’till the inside of the cell was perfectly smooth— the superfluous mud was by this excavating process brought up to the edge of the cell and rapidly smoothed on the innerside—

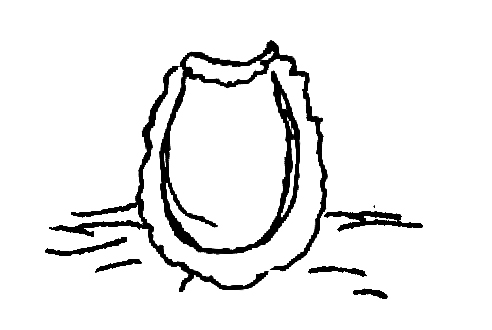

Other cells made by the same insect were complete, & they presented this form

they would just have held the somewhat short & thickset bee, if the parts (legs wings &c) were closely packed together— One other thing I observed, & was much struck with, when the insect was at work (& she worked with great rapidity) was the apparently intense disinclination to shift her position whilst at work— I thought to myself—you stupid little wretch why don’t you get round ‘tother side, you would then get at it (the cell) more comfortably— well she did move after a time—’

they would just have held the somewhat short & thickset bee, if the parts (legs wings &c) were closely packed together— One other thing I observed, & was much struck with, when the insect was at work (& she worked with great rapidity) was the apparently intense disinclination to shift her position whilst at work— I thought to myself—you stupid little wretch why don’t you get round ‘tother side, you would then get at it (the cell) more comfortably— well she did move after a time—’

Well that’s all the “facs” of the case— No! there’s one point more to mention— When the cell is deep enough a lid is put on to the top, and as the under, or inner side of the lid could not be smoothed, it is left rough, but the outer or upper side is hollowed out & smoothed exactly like the pellet which was first deposited, and indeed it is an exact repetition of the first commencement of the cell—

Part II. Crotchets [DOUBLE UNDERLINED]

Well when I began to think about this matter, one of the first points that struck me was the Bee was not such a stupid, as I had thought it not shifting herself about so quickly as she might have done—for by keeping the body fixed in one position for some time & by working in all directions as far as she could reach, in her excavating, she would necessarily form a cavity in segments of circles and of a definite size— —the diameter being determined by her power of reaching, without shifting the hinder part of her body—thus had she had longer legs she would have made a cavity of greater diameter because she could reach further— Then I further thought that in her after proceedings, the curve gained in forming the first cavity (which may have been about d of the entire cell) would in all probability affect the curves which were to follow, & thus that the insect (without necessarily thinking at all about the matter) would, as she proceeded gradually find the sides of the cell closing in upon her, & at last to such a degree that she could not get her head in to excavate any more— well, but she could begin afresh—& she does so—the lid of the cell is, as I have said, exactly the counterpart of the beginning of a cell—

Another thing which suggested itself was this—that the cell made by the Osmia bore about the same proportions to the insect that made it, as does a certain cell made by the Hive bee to that insect—I allude, of course to the queen’s cell, which is built separately— Then I called to mind the state of affairs to be noticed in the regeon of the queen’s cell—viz. little, rounded, cavities and little cavities which are not rounded, but all sorts of shapes—with straight sides to them, and the number of sides varying much—sometimes may be seen a cavity with one side straight the remaining part rounded & from such cavities, which answer no purpose whatever, that one can discover, we find every intermediate grade up to a perfect cell—hexagonal, or pentagonal or anything agonal—in all cases the number of sides being accompanied (to say the least of it—I wont say determined, for you will be down upon me) by an adjoining cell for every flat side— There’s no crotchet in that—it’s a “fac”—

The closing time has come & I must finish my letter tomorrow, but that you may not think I have forgotten you I will send this off—

Yours truly | Geo R Waterhouse

In great haste

CD annotations

Footnotes

Bibliography

Correspondence: The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt et al. 29 vols to date. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985–.

Natural selection: Charles Darwin’s Natural selection: being the second part of his big species book written from 1856 to 1858. Edited by R. C. Stauffer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1975.

[Waterhouse, George Robert.] 1835. Bee. In The penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, edited by Charles Knight, vol. 4, pp. 149–56. London: Charles Knight.

Summary

Bees’ cells. Observations on Osmia atricapilla.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-2213

- From

- George Robert Waterhouse

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- British Museum

- Source of text

- DAR 181: 22

- Physical description

- ALS 7pp †

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 2213,” accessed on 24 November 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-2213.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 7