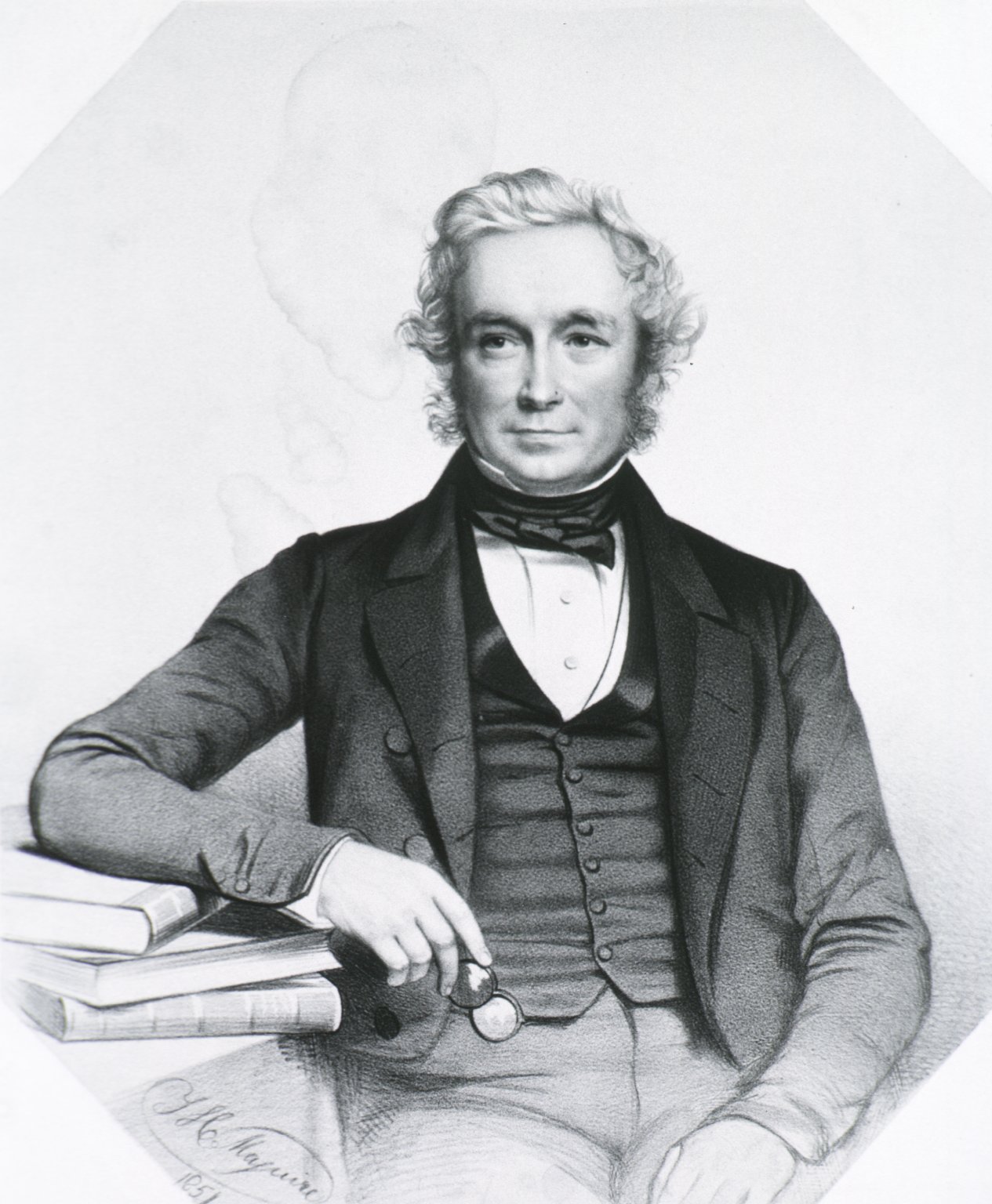

The letters Darwin exchanged with John Stevens Henslow, professor of Botany and Mineralogy at Cambridge University, were among the most significant of his life.

It was a letter from Henslow that brought Darwin the invitation to sail round the world as companion to captain Robert FitzRoyof HMS Beagle - Henslow had recommended him not as 'a finished naturalist', but as a personable young gentleman, able to take advantage of the opportunity to study the natural world. As a student, it had been walks in the Cambridgeshire countryside with Henslow that had fostered Darwin's interest in a range of plants and animals, and inspired thoughts of travel. Once his place on the Beagle was assured, Henslow gave Darwin a present of Humboldt's Narrative, a much loved account of earlier travels in South America that Darwin kept to the end of his life, and which is now in Cambridge University Library. It is inscribed: 'J. S. Henslow to his friend C. Darwin on his departure from England upon a voyage around the World. 21st Sept. 1831'.

For goodness sake what is No. 223- it looks like the remains of an electric explosion

During the voyage it was Henslow who received the vast numbers of specimens Darwin sent home, and Henslow who wrote with practical advice about how best to prepare, preserve, and ship them. And the scientific world first took notice of a young traveller called Charles Darwin when Henslow read some of his letters from South America to the Cambridge University Philosphical Society. After Darwin's return Henslow continued to assist in the distribution of the specimens to various experts, though the task of classifying the Beagle plants was eventually passed on to Joseph Dalton Hooker at Kew.

As a schoolboy Henslow had assisted in cataloguing the zoological collections of the British Museum; as a student in Cambridge he discovered a new species of freshwater snail, named after him, and began a life-long friendship with Adam Sedgwick, Professor of Geology, who introduced him to field studies. In 1819 Henslow carried out a field survey of the Isle of Man, and two years later made a comprehensive study of the geology of the island of Anglesey. He launched his plant collecting quite suddenly in March 1821, and by the end of the year had collected 263 flowering plants. In 1822, Henslow was appointed Professor of Mineralogy at Cambridge University, and, less than three years later, at the age of 29, was also awarded the Chair of Botany. He resigned the Chair of Mineralogy in 1827, but remained Professor of Botany until his death in 1861. As Professor of Botany he successfully campaigned for a new and much larger site for the Cambridge University Botanic Garden.

Despite Henslow's reservations about the evolutionary ideas put forward in Origin - he thought Darwin had 'pressed his hypothesis too far' - the two men remained friends to the end of Henslow's life; more than 140 letters between them survive. Darwin continued to rely on Henslow for information on a variety of plants, and wrote of him after his death 'a better man never walked this earth'.

Henslow was curate of Little St Mary's Church, Cambridge, from 1824 to 1832, then vicar of Cholsey-cum- Moulsford, Berkshire, and finally rector of Hitcham, Suffolk, from 1837, a post he also held until his death.

ODNB article: https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/12990