We know of letters to or from around 2000 correspondents, about 100 of whom were women. Using the letter summaries available on this website, the letters can be assigned to rough categories. Included in the count are letters to women in Darwin's family that contained messages for Darwin.

Nearly half of the surviving 650 or so letters to or from women are to do with family matters. Despite the fact that Darwin and his wife Emma were rarely separated after their marriage, the correspondence between them is the largest surviving one between Darwin and a woman. The next biggest block after family matters, around 76 letters, might be described as observations. These were from women - often strangers - who had read Darwin's work, had noticed something that they thought might interest him, and wrote to him about it; or they might be letters to or from friends and relations who had been asked by Darwin to make specific observations. The next biggest - around 64 letters - is to and from botanists. This term was used to cover women who were publishing on botany or who were acknowledged by their contemporaries to be skilled practitioners. Botanists carried on the most lengthy and detailed correspondences with Darwin of all his female correspondents other than close family members. Botany was a popular subject for women to take up: it could be learnt and practised at home. One of Darwin's botanical correspondents, Mary Treat, was also an entomologist, and one woman wrote to him about geology.

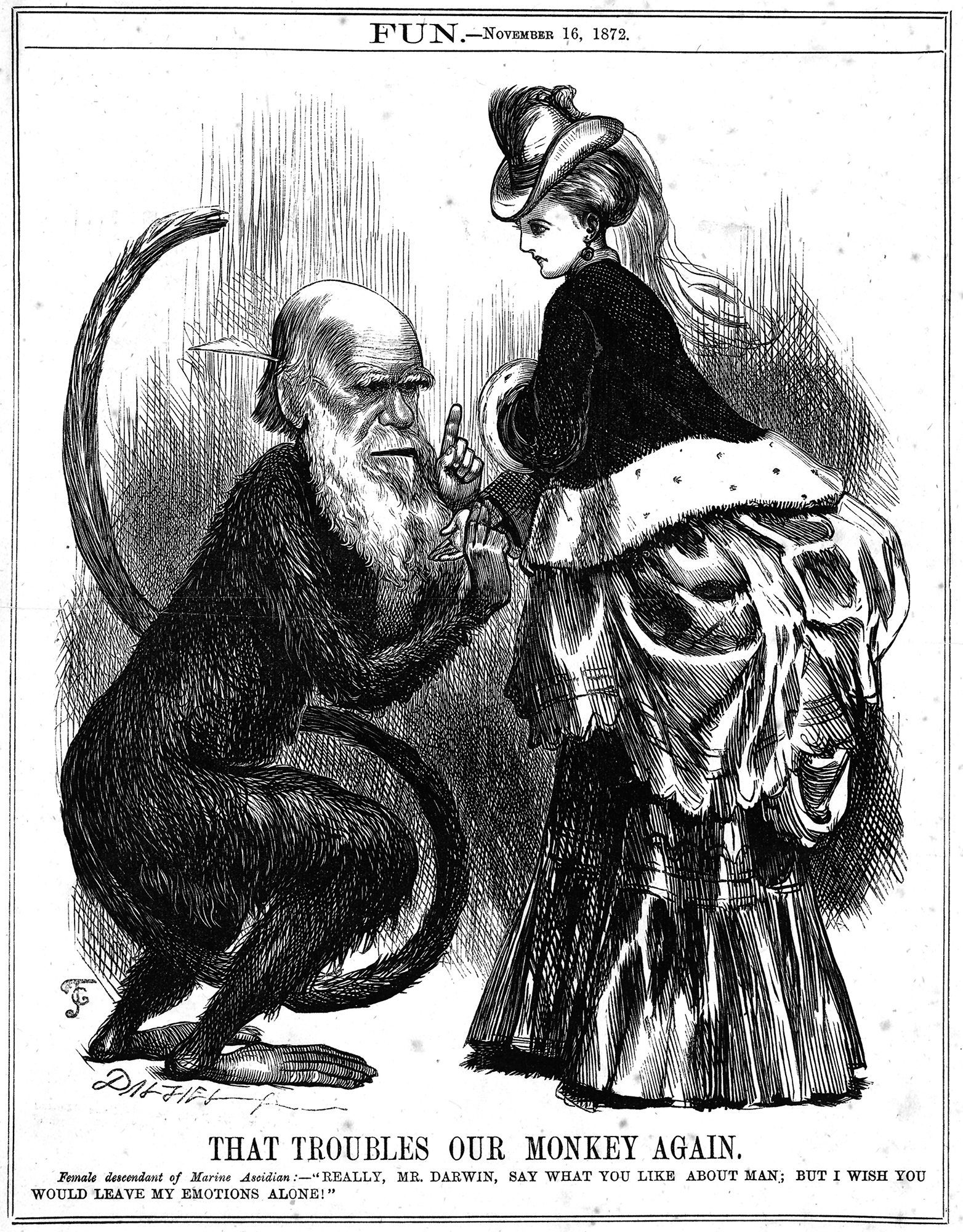

After these categories come in descending order: friends; go-betweens (women writing on behalf of a man); writers (usually women writing on science); and editors (there is a substantial correspondence between Darwin and his daughter Henrietta about the editing of his works). Another category that suggested itself but it was omitted since it cut across too many others was "trying to get a pension for someone". Some letters didn't sort easily into any category at all, such as instructions for making ginger beer and someone seeking to sell a portrait of Erasmus Darwin. In addition there are a small but interesting set of letters in which women challenged Darwin on his views on religion or women's place in society.

The correspondence reveals that Darwin was happy to rely on women for observations (relatives might be roped in to search for plants, for example, or to survey the amount of earth turned over by worms), experimental work, editorial help, and advice on presentation. We know from Darwin's own comments that Emma was prepared to tell him whether a paper he liked was too boring to republish, and that the women in the family reined him in when he wrote to his Roman Catholic adversary St George Jackson Mivart. Henrietta was a valued editor of his works. In his correspondence with women botanists, Darwin was neither dismissive nor patronising. If he was interested in their findings he urged them to publish, because it was better for him to refer to published works. He didn't see women exclusively in ancillary roles: he knew women who published in their own right, and he must have been aware of arguments that the generally inferior intellectual status of women was maintained artificially by their exclusion from examinations and learned societies. He supported women's education in physiology, even though some thought it an unfeminine (messy and heartless) subject.

Darwin's comments on the "difference in the mental powers of the two sexes" in Descent of man 2: 326-9 are complex, and further complicated by views on inheritance that might seem strange today. He begins with a nod to the view that there is no difference, which he denies, not, at first, on the grounds of women's lesser intelligence, but on the grounds of their greater tenderness. So far, so conciliatory; a difference in disposition is something Darwin can support from observations of other mammals. Men, on the other hand, have the "unfortunate birthright" of competitiveness (inherent in male competition for females), which can lead to selfishness. However, men have achieved higher eminence in all fields; and Darwin attributes this not to social causes, but to the very habit of dogged persistence that he thought arose from constant competition. (This view of the key to male success is interesting in the light of Darwin's own opinion of his "genius"; he suggested the motto "It is dogged as does it" for scientific workers, and generally thought patience and persistence more valuable than inspiration.) Additionally, Darwin thought that constant fighting and hunting would have led to greater "observation, reason, invention or imagination". (He does not discuss whether the conditions of female life, even stereotypically confined to childcare, housekeeping, and "gathering", would have developed similar qualities.)

At this point, Darwin applies his own logic of inheritance. Darwin believed that faculties developed later in life were likely to be transmitted only to one's own sex, whereas faculties developed earlier in life could be transmitted to both. Hence, the particular skills that men acquired through adult conflict and struggle would tend to be passed to their sons only, entrenching sexual difference.

By the end of this passage, Darwin has concluded that "man has ultimately become superior to women", and is expressing relief that equal inheritance of characters has generally prevailed among mammals, otherwise "man would have become as superior in endowment to woman, as the peacock is in ornamental plumage to the peahen". This seems a conservative conclusion: but he believes that women can, with an effort, raise themselves to the same standards as men. The measures he describes (training in energy and perseverance; having her reason and imagination exercised to the highest point) suggests that the effort involved amounts to having the same education as men, who must maintain their superiority in a similarly effortful way. Oddly, though, he can only imagine this improvement being disseminated infinitely slowly (if at all), by inheritance from a few educated women, rather than more rapidly by universal education.

When he was asked by Caroline A. Kennard, an American campaigner for women's education, to explain his views, Darwin responded as follows:

The question to which you refer is a very difficult one. I have discussed it briefly in my 'Descent of Man'. I certainly think that women though generally superior to men [in] moral qualities are inferior intellectually; & there seems to me to be a great difficulty from the laws of inheritance, (if I understand these laws rightly) in their becoming the intellectual equals of man. On the other hand there is some reason to believe that aboriginally (& to the present day in the case of Savages) men & women were equal in this respect, & this wd. greatly favour their recovering this equality. But to do this, as I believe, women must become as regular 'bread-winners' as are men; & we may suspect that the early education of our children, not to mention the happiness of our homes, would in this case greatly suffer. (Darwin to C. A. Kennard, 9 January 1882)

Kennard responded (C. A. Kennard to Darwin, 28 January 1882) that to all intents and purposes, women were already breadwinners; that they often had to earn money to put their brothers through college, and that the mental exercise of running a household was fully equivalent to that of paid employment.

No doubt many reasons underlie Darwin's conservative yet courteous and somewhat provisional account of the female intellect. If Darwin's account seems contradictory, and at odds with his personal knowledge of talented and intelligent women, it's perhaps because he believed in the plasticity of evolving species much more than we do now. Nowadays it's axiomatic in some circles that humans have not been civilised for long enough for much impact to have been made on our Stone-Age genes, so that arguments about gender difference and gender equality are often based on assumptions about prehistory, awkwardly enough. But for Darwin, the conditions of his own era were having an immediate impact, and if conditions changed, so might the biological restraints on the sexes. He was conservative in his views and not sure that would be a good thing; but he didn't think it was an impossible thing. He supported his undoubtedly traditional views with the logic of inheritance as he saw it, but he wasn't entirely sure he'd got that right. Perhaps that accounts for his generally genial and supportive relationships with women.