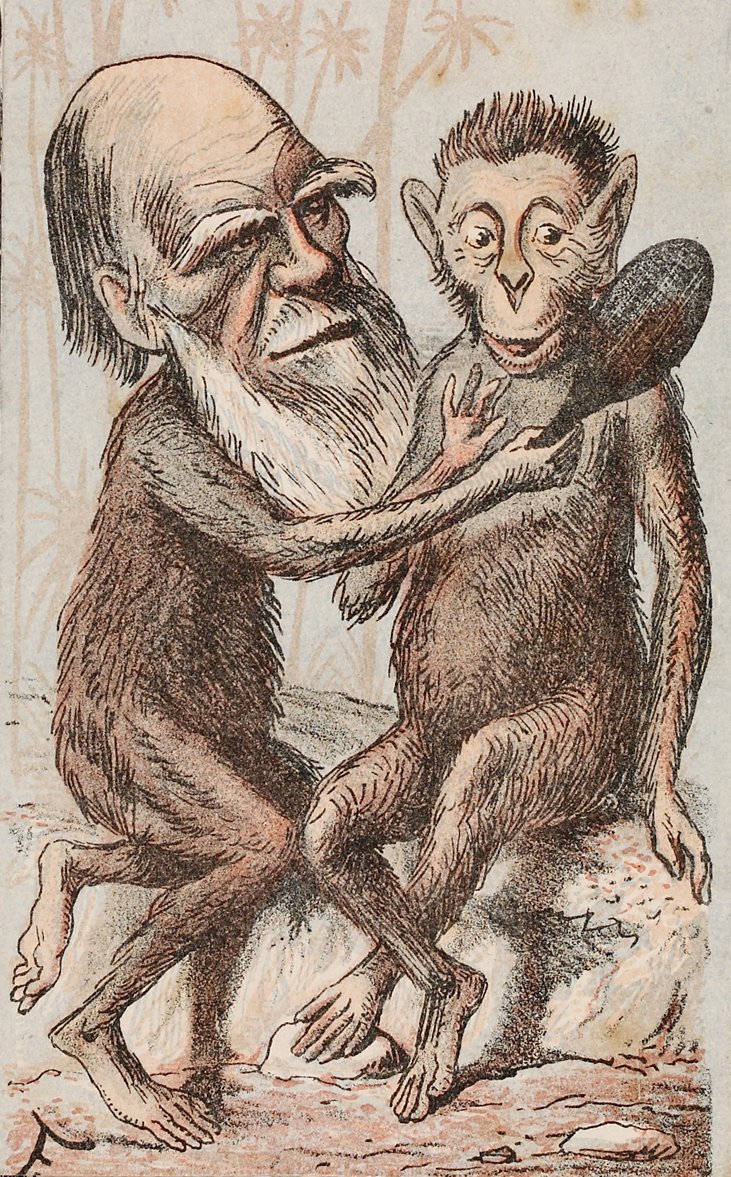

The early 1870s were a turning point in the global debate about human evolution, with deep implications for science, colonial expansion, industrial progress, religious belief, and ethical and philosophical debate. Darwin’s correspondence from this period is of fundamental importance for understanding both the development of his theory of human origins and its relationship to prevailing assumptions about human nature.

The extension of evolutionary theory to humans was the most controversial aspect of Darwin’s work in his own day, and it remains the most contentious point in the global debates over Darwinism. Scholars and scientists still disagree about the evolution of moral behaviour, religious temperament, aesthetic taste, and creative potential.

Although Darwinism is still often used to justify competition in human societies, in fact Darwin challenged the primacy of self-interest and gave a new foundation to traditional virtues such as compassion, sympathy, and love. He rooted ethics in animal instincts, but argued that such instincts are modified and strengthened in human societies through the power of natural selection, through our experience of approbation and shame, and through the influence of education and religion. In the Descent of Man, Darwin argued that the golden rule – “do unto others as you would be done by” – could be explained by a scientific, evolutionary, understanding of the development of human behaviour. The irony of this was not lost on him: about this passage he wrote to his daughter Henrietta, “I fear parts are too like a Sermon. Who would ever have thought that I should turn parson?”

The Letters

The nineteenth century debates about the application of evolutionary theory to human nature that centred on Darwin’s work still continue in a variety of scientific and popular domains, and are nowhere more vividly brought to life than in Darwin’s own letters. The period leading up to and including the publication of Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871) andExpression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) saw the greatest expansion and diversification of Darwin’s correspondence network. In order to extend his theory of evolution to humans, Darwin gathered an extremely wide range of information. He made an exhaustive survey of sexual characteristics and emotional behaviour in the animal kingdom; he observed infants and collected photographs of asylum patients; he solicited accounts of emotional states in aboriginal peoples. Darwin encouraged openness in his correspondents, and the observations he received were often accompanied by lengthy descriptions of the social contexts in which facts were recorded, and accounts of the feelings and views of the observers themselves. Only a small proportion of this wealth of material appeared in Darwin’s publications, yet it is deeply revealing of the complexities of the debates, and the range of participants and viewpoints involved. The letters are thus of fundamental importance for understanding both the development of Darwin’s theory of human origins and the relationship between his theory and prevailing assumptions about human intellectual and moral nature.

Exploration of the origins and development of mind, morality, and religious temperament were a vital part of the extension and defence of Darwin’s theory of species transmutation. These higher faculties seemed to most of Darwin’s contemporaries uniquely human, and they served as evidence of the essential distinctness of humans from other animals. They are still cited today as barriers to an acceptance of the evolutionary mechanisms of natural and sexual selection. The correspondence, which shows Darwin in dialogue with scientific colleagues, religious figures, family and friends, many of whom had grave doubts about his views on human evolution, allows these questions to be raised in new ways, and in a manner that is conducive to discussion among a wide audience. Much of the scholarly attention to Darwin’s views of human nature has focussed on ‘social Darwinism’ and the eugenics movement that were promoted in the second half of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century. Darwin’s correspondence sheds much light on the complexity of these debates in Darwin’s own time. It also shows that the implications of Darwin’s work were extremely broad in their bearing on discussions of progress, liberalism, freedom of thought, and the advance of European civilization.

Volume 19 of The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, contains more than 800 letters from the year 1871 when Descent of Man was published, many of them on the subject of human nature. A selection of the most important are being made available here, in advance of full online publication of the volume, as part of the Human Nature initiative. All the letters from that year will go online in 2016.