From Fritz Müller 15 June 1869

Itajahy, Sa Catharina, Brazil

June 15. 1869.

My dear Sir.

I have been prevented from answering sooner your kind letters of March 14th and 18th by a botanical excursion, I made last month.1

I do not know how to express my warm gratitude for all the pains, you have taken in the publication of the Translation of my little book, to which, after all, you attach far too much importance.2 The three copies have arrived here safely; many thanks for them. I have been much gratified by the appearance of the book in its English dress, as well as by the Translation, which appears to me to be very good. I have to thank you also for the reviews in the “Athenæum” and the “Scientific Opinion”, which you have kindly sent me. I am sorry to learn from these reviews, that some expressions of mine have shocked the religious feelings of one of the reviewers.3 I should indeed have suppressed or modified some passages, before offering my book to English readers.—

As to Faramea, I am quite sure, that the two forms are really the long-styled and short-styled form of a single species.4 The plant is very common in my own forest, and after examining numerous specimens, I cannot find any difference between the two forms excepting those in the sexual organs. The size of the flowers varies much, but is not characteristic of either form. Some long-styled flowers, which I had fertilized artificially with pollen from the opposite form, are yielding fruits.— A second very beautiful species of the same genus which grows near the mouth of the Itajahy, is probably also dimorphic; I have hitherto examined the flowers of only one plant; these were longstyled and the styles as long as in the longstyled form of the first species.—

Many thanks for the Eschscholtzia—seeds, which will be sown in a few weeks.— It is curious to see, on what trifling circumstances fertility sometimes depends.5 Thus I have in my garden several specimens of an endemic Irideous plant (Cypella?), which I suspected to be self-sterile.6 I fertilized repeatedly numerous flowers with pollen of the same and of distinct plants, without obtaining a single pod. The unprotected flowers were regularly visited by insects; by these also, for months, did not yield a single fruit, when unexpectedly all the flowers, about 20 in number, which had opened on a certain day, produced fine pods. The plants have continued to flower after this time for many weeks, but without producing any more pods.—

That curious grass with spirally contracting barbs, the Streptochæta, appears to be extremely rare here.7 I have looked in vain for more specimens at different localities; that part of my forest, where I had found it first, had been cut down in the meantime; a single specimen, which I had planted in my garden, seems to thrive well and will, I hope, furnish me with an opportunity of settling the points to which you allude in your letter.8

From seeds of a long-styled white Oxalis, legitimately fertilised with pollen of the longer stamens of the mid-styled form I raised some plants; 8 of these have hitherto flowered and of these 4 are long-styled, 4 mid-styled and none short-styled.9

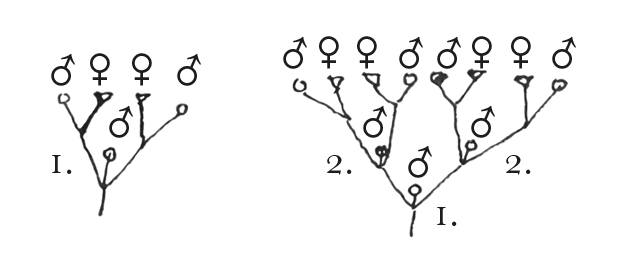

I enclose seeds of the second plant of Begonia with monstrous flowers, of which I told you in my last letter. In this species, (probably the Begonia obliqua of the Flora fluminensis),10 the panicles generally consist of either 5 or 11 flowers, of which 3 or 7 are male ones and the rest female ones and which are arranged in the following manner

The male flowers (1) and (2) are often quite regular, or but little modified, one or two of the central stamens having the connectivum enlarged and provided with rudimentary stigmatic papillæ, whilst in those male flowers, which stand at the side of a female one, from one to three (or in the second plant even as many as 8) stamens are more or less completely transformed into pistils.

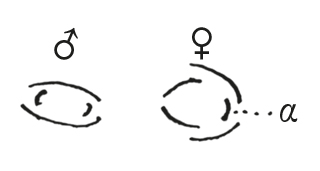

The female flowers have generally 5 divisions or petals, one of which is much smaller than the rest.

This small petal (α) and the male flower, which springs from

the same point with the female one, are always placed on opposite sides of the latter. Sometimes the male flower is wanting and in this almost always a sixth petal (β) is present in the female flower.

the same point with the female one, are always placed on opposite sides of the latter. Sometimes the male flower is wanting and in this almost always a sixth petal (β) is present in the female flower.

May we not venture to admit, that the abortion of the sixth petal in those female flowers, which are accompanied by a male one, is due to the pressure exerted on the young buds by the male flowers? And not the reappearance of the sixth petal in most of the cases, in which this pressure does not exist, be compared to the reappearance of a regular structure (pelorism) in central or terminal flowers?—11 In irregular flowers it is almost always, as far as I know, the posterior stamen, which first aborts, and this abortion might be explained by a pressure caused by the axis, from the side of which the flower springs. Now, if a flower-bud be placed at the very end of the axis, no such pressure could possibly be exerted; all the segments of the flower would have exactly the same position in relation to the axis; there would be no reason for one of them differing from the rest and thus the flower would become regular even without the law of reversion coming into play.

With sincere gratitude and respect, believe me, dear Sir, | very truly yours | Fritz Müller

CD annotations

Footnotes

Bibliography

Baker, Herbert G. 1956. Pollen dimorphism in the Rubiaceae. Evolution 10: 23–31.

Correspondence: The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt et al. 29 vols to date. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985–.

Cross and self fertilisation: The effects of cross and self fertilisation in the vegetable kingdom. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1876.

Flora fluminensis. By José Mariano da Conceição Velloso. 11 vols. Paris: A. Senefelder, 1827.

Forms of flowers: The different forms of flowers on plants of the same species. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1877.

[Leifchild, John R.] 1869. [Review of Facts and arguments for Darwin by Fritz Müller, translated by W. S. Dallas.] Athenæum, 27 March 1869, p. 431.

Müller, Fritz. 1864a. Für Darwin. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann.

Origin: On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1859.

Variation: The variation of animals and plants under domestication. By Charles Darwin. 2 vols. London: John Murray. 1868.

Summary

FM much gratified by the appearance of Für Darwin translation.

Discusses dimorphism in Rubiaceae.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-6783

- From

- Johann Friedrich Theodor (Fritz) Müller

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- Santa Catharina, Brazil

- Source of text

- DAR 110: B115; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (Directors’ Correspondence 215/175)

- Physical description

- ALS 4pp ††

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 6783,” accessed on 18 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-6783.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 17 and 24 (Supplement)