From R. B. Litchfield [before 2 December 1871]1

Origin of Music— Note on H. Spencer’s Essay— (p. 359 of Volume)2

I think Spencer’s speculations are very ingenious & up to a certain point—sound—that he establishes satisfactorily the connection between utterance of musical sounds and the physiological effects of pleasure & pain. But he seems to me to strain his theory very much in trying to make out that the muscular expression of emotion is a complete explanation of the origin of Musical Expression.3

See. p. 368. 7 lines from bottom.

In this passage he sums up the results of what precedes far too broadly. All he is entitled to say is that the vocal peculiarities wh. indicate excited feeling are those which distinguish the elements of song from speech.4 Supposing that he has accounted for the production of musical sounds. But it is the combination of these that makes music—& musical expression, and the step from the elements to combination, seems to me a step infinitely more important than the step from speech-sound to musical sound.

The great law about the expression conveyed in music is that it depends wholly on the relations of the sounds to each other & not at all on the absolute pitch of any sound— A high sound, as such, conveys no more expression of despair joy &c than a low sound—the expression is entirely in the sequence— The tune played by the ophicleide and the flute is still the same tune— the pitch makes not the least difference in its form or expression— The difference is only such as exists between two engravings of the same design, one in red ink, the other in brown. The difference is not so great as this because there is a real element in common viz. the harmonies in each case5

There is moreover a great law underlying all music of wh. Spencer takes no account and wh. modifies considerably some of his reasoning. It is a fact that the sounds most easily uttered are sounds related in the way described by the word “scale” and that the position of sounds in the scale is the one thing on wh. their effect depends (I don’t mean causatively, but that the main difference of effect corresponds to the difference in character described by the phrase “position in scale”).

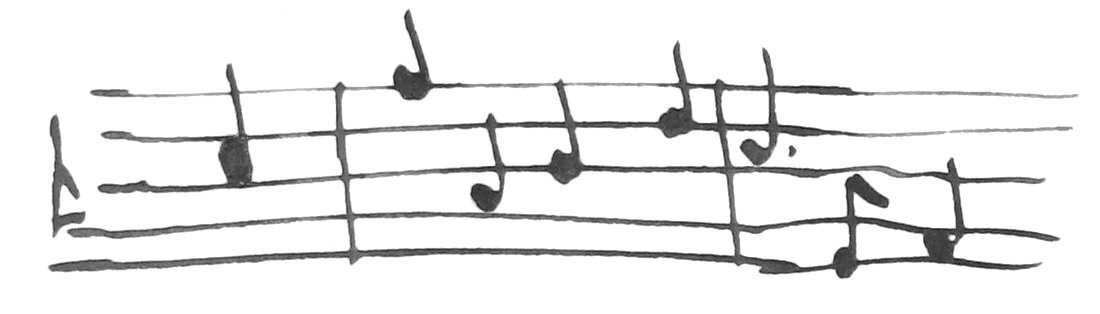

Spencer says (middle of p. 369) that the employment of larger intervals is a trait of strong feeling. This is not wholly wrong but is a very imperfect & incorrect way of putting the truth. A phrase full of large intervals such as

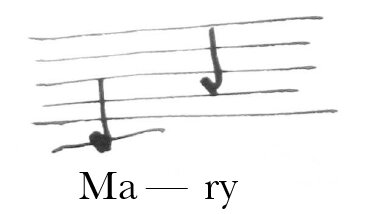

may have the effect of perfect calm— in the instance given I should refer the effect to the fact that the melody is framed on what is called the “common chord” i.e the set of sounds wh. are spontaneously generated according to the physical laws of the vibrations out of any sound taken as a starting point (the set of sounds wh. a trumpet, a bell, or a string utters along with the primary sound). The voice utters these sets of sounds more easily & naturally than it utters any other sequence of sounds so that emotion of any kind finds in these sounds its most natural expression.6 Such calls as Spencer talks of at p. 366 are usually on notes thus related.7 I noticed this myself, as I often do, when hearing some one at Down calling up the stairs to a servant— the sounds were then I think these:

a sequence wh. happens to be about the most pleasing that exists: and in the calls of news boys &c I often observe that the cadence naturally runs into the same interval, or the “Octave”.

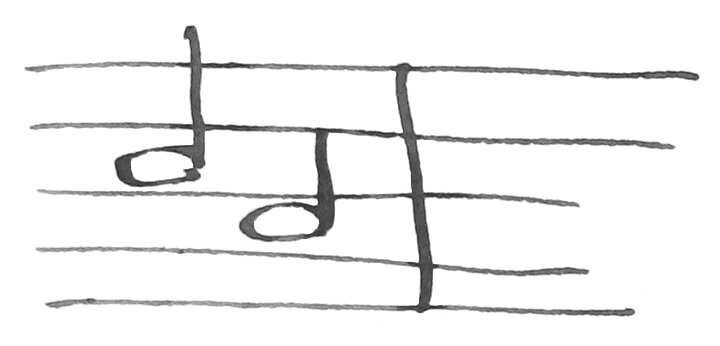

Why certain scale intervals have a character why, for instance, the drop from “do” to “la”

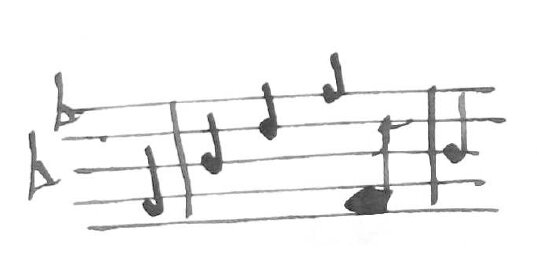

has a wailing melancholy effect (when the music is what is called “in the key” of “Do” but not otherwise) no one knows: and I am not aware that a theory of the cause has been even suggested. Certainly nothing in Spencer’s speculation gives any approach to an answer to the question. It is the group of such facts, stated in another way, which he refers at the top of page 376 (line 3). He says “few will be so irrational as to think this”.8 But this remark is absurd. There is nothing irrational in stating that certain mental effects are always associated with certain physical phenomena. No one means more than this when they say the ratio of the no. of vibrations is the cause of the & mental effect. Any one wd. say that a scarlet & blue flag was a more joyous & exciting piece of colour than a flag of brown & grey. In the same way there is no doubt that of the phrases

|

& |

|

played with equal speed & loudness the first is more vigorous, brilliant, & joyous than the 2nd: it is this kind of difference of wh. Spencer takes no notice, & it is the sum of these differences wh. in effect constitute Music.

To repeat, however, Spencer seems irrefutable in his theory as to the production of the elements of music: and I am not sure that his view may not contain a clue to the solution of the other problem, the question of the origin of musical expression proper. It is a fact that common-chord sounds are, physically, easiest to utter—and if we treat all music as a reflex of voice music, it might be possible to trace in this fact some explanation of the mental effects of certain sequences of sounds. But I cannot see my way farther than this hint of a possible law.

CD annotations

Footnotes

Bibliography

Offer, John. 2010. Herbert Spencer and social theory. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Spencer, Herbert. 1858–74. Essays: scientific, political, and speculative. 3 vols. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts; Williams & Norgate.

Summary

Discussion of H. Spencer’s views on the origin of music.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-8129

- From

- Richard Buckley Litchfield

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- unstated

- Source of text

- DAR 89: 121–7

- Physical description

- mem 9pp

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 8129,” accessed on 24 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-8129.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 19