From Fritz Müller 12 January 1869

Itajahy, Sa Catharina, Brazil

January 12. 1869.

My dear Sir

As the Eschscholzia-seed, which I formerly sent you, has not germinated, I send you some fresh seeds from my plants, which this summer again have proved self-impotent.1

The plants raised from your seeds have suffered so much from the extraordinary heat and the heavy thunderstorm, which in November followed after an extremely rainy winter and spring, that I could make but very few experiments.2 Only four plants escaped and three of these flowered tolerably well. My own plants, which were introduced here about six years ago, suffered but little from the weather and none has perished.—

Here are the experiments, I tried on the Eschscholzia raised from your seeds:

| First plant: | ||||||

| 1.) | Octbr. 23. | A flower fertilized with its own pollen. | ||||

| Novbr. 15. | Germen, 12mm long, begins to whither. | |||||

| 2) | Novbr. 3. | Fertilized two flowers, one | ||||

| (a) with pollen from a distinct flower of the plant, the other | ||||||

| (b) with pollen from a distinct plant. | ||||||

| Novbr. 5. | Stigmas of the flower (a) fresh, those of (b) withering | |||||

| Novbr. 9 | Germen of (a) | 12mm, | of (b) | 26mm long | ||

| Novbr. 11 | .... | 19mm, | .... | 47mm— | ||

| Novbr. 15 | .... | 30mm, | .... | 56mm—. | ||

| Novbr. 30. | Fruits ripe; the pod | |||||

| (a) 32mm long, with 10 seeds, 4 of which are very small; the pod | ||||||

| (b) 58mm long, with 59 good seeds. | ||||||

| 3) | Novbr. 9 | Repeated the same experiment. | ||||

| Novbr. 10 | Stigmas of | (a) fresh, | those of (b) | withering. | ||

| Novbr. 15 | Germen of (a) | 11mm, | that of (b) | 18mm long | ||

| Novbr. 18. | — — — | 12mm, | — — — | 49mm long. | ||

| The pod (a) fell off unripe; the pod (b), | ||||||

| 53mm long, yielded 45 seeds (Decbr. 4.) | ||||||

| Second plant. | ||||||

| 1.) | Novbr. 1. | Fertilized two flowers with each other’s pollen. | ||||

| Novbr. 2. | Stigmas withering, having remained in a horizontal | |||||

| position in one of the flowers, while the had become | ||||||

| [exerted] in the other. | ||||||

| Novbr. 9. | Germens | 16mm | and | 46mm | long | |

| Novbr. 11. | — — — | 17mm | — | 50mm | — | |

| Novbr. 15. | The smaller germen withered, the larger 53mm long | |||||

| Novbr. 30. | Pod ripe, 56mm long, with 24 apparently good seeds | |||||

| (a remarkably small number for so large a pod.) | ||||||

| 2.) | Novbr. 19, | midday. Fertilized one flower | ||||

| (a) with pollen from a distinct flower of the plant; a second flower | ||||||

| (b) with pollen from a distinct plant; a third flower | ||||||

| (c) simply protected from insects. | ||||||

| Novbr. 22. | Germens of (a) and (c) 10mm, that of (b) 16mm long | |||||

| Novbr. 27. | Germen of (a) 40mm, of (b) 64mm, of (c) 32mm long. | |||||

| The extremity of the germen (c) putrifying. | ||||||

| Novbr. 30. | Germen of (a) 40mm, that of (b) lost by an accident, | |||||

| that of (c) withered. | ||||||

| Decbr. 13. | The pod (b) ripe, 45mm long, with 9 seeds. | |||||

| 3.) | Novbr. 25. | Fertilized two flowers | ||||

| (a, b) with pollen from distinct flowers of the plants, and one flower | ||||||

| (c) with pollen from a distinct plant. | ||||||

| Novbr. 30. | Germen of (a) not increased, (b) 10mm, (c) 27mm long. | |||||

| Decbr. 6. | Germen (a) and (b) withered; (c) 40mm long. | |||||

| Decrb. 17. | Germen (c) putrified. | |||||

A third plant, all the germens of which withered or putrified, showed the same difference in the growth of the germens fertilized with the same plants and a distinct plant’s pollen: The experiments ought to be repeated on a larger scale and on healthy plants.

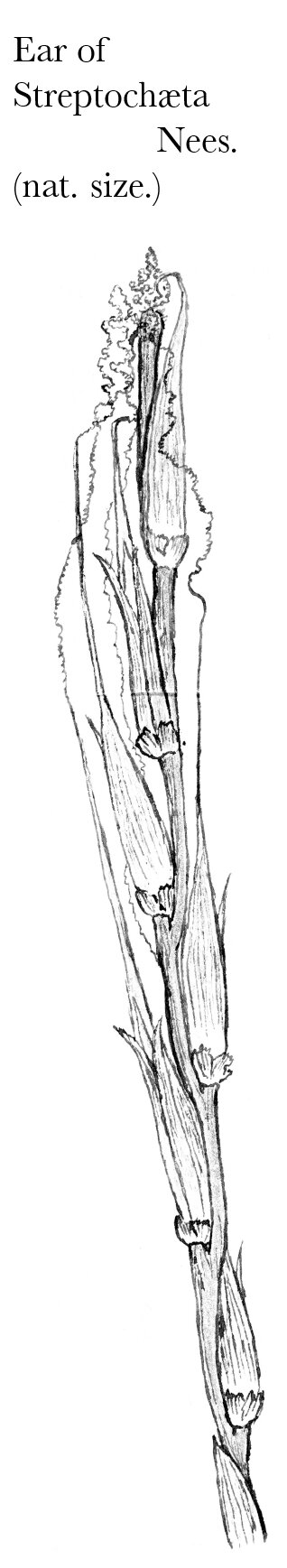

I have lately met with a most curious grass, the Streptochæta Nees.3 The rhachis of the simple ear is prolonged beyond the last floret and its extremity is club-shaped and densely covered by strangely curled short, stiff hairs. Each floret has an extremely long barb, which adheres to the club-shaped extremity of the rhachis and then contracts spirally in reversed directions, just as a tendril would do after having caught a support. This is effected long before the ear begins to peep out from the enclosing leaves. When the seeds are ripe, the florets hang down, by means of their tendril-like barbs, from the tip of the rhachis,—probably till they are carried away and disseminated by some passing-by animal. It is curious that a contrivance for dissemination shd be formed at so early a period, long before the flowers expand.— Under a morphological point of view, the Streptochæta is not less remarkable; Endlicher, indeed, calls it “gramen ad modum paradoxum”.4 There are not only six stamens and three stigmas (as in a few other grasses, Pharus, ec.), but also six leaves in two whorls surrounding the sexual organs. Thus Streptochæta forms a connecting link between common grasses and other monocotyledons, in the same way, in which some “paradoxal” animals (such as Lepidosiren, Ornithorhynchus ec.) connect classes now widely separated.5 I think we may look at it as a very old form, much less modified in structure of its flowers, than any other living grass.—

Our Brazilian cuckoos, according to Burmeister, agree in their habits with the North-american species;6 but we have here another bird, not belonging to the cuckoo-family, which, like the European cuckoo, lays all her eggs, as far as I can make out, in other birds’ nests. In the nests of the Tico-tico (Zonotrichia matutina Gray)7 and other small birds a white egg, about 24mm long and 18mm in diameter, with the two ends equally rounded, is occasionally found. Sometimes even two of these eggs are found in the same nest. I have inquired several boys, who attend much to birds’ nests, but none had ever seen a nest containing only these white eggs and which therefore might have been supposed to be the own nest of the parent-bird— I am told, that this bird is a Trupialis.8 I wished to raise young birds; but one, which I found this summer was devoured by a snake or bird of prey, when three days old, and another was destroyed by a thunderstorm.—

On an ear of maize I found, last year, six dirty bluish-grey grains, the rest being pale-yellow. I sowed separately the bluish and the yellow grains; on 30 pale-yellow ears, from the yellow seeds. There were but 5 bluish grains and 4 were spotted with violet. On 3 pale-yellow ears, from the bluish seeds, there were 581 pale-yellow and white, 193 bluish grains and 78 of mixed colours (yellow with bluish ring, or spotted with violet, or dark bluish-grey with a white central spot ec.)— 9 ears from the yellow and one from the bluish seed had reverted to the colour of their grandmother which had dark brown grains. Gaertner, as you know, obtained similar results (Bastarderzeugung pg. 322):9 On the hypothesis of Pangenesis the fact might be explained by assuming, that in the seeds of each individual flower the gemmulæ derived from this flower are more numerous than those from any other flower of the plant, and that therefore in the offspring flowers of the same kind are more numerous, than in the mother-plant.—10 Do you think, that this will hold good as a general rule? I intend to try some experiments on plants which bear at the same time flowers with 4, with 5 and with 6 petals.—

With sincere respect | very faithfully yours | Fritz Müller.

CD annotations

Footnotes

Bibliography

Burmeister, Karl Hermann Konrad. 1854–6. Systematische Uebersicht der Thiere Brasiliens, welche während einer Reise durch die Provinzen von Rio de Janeiro und Minas geraës gesammelt oder beobachtet wurden. 3 vols. Berlin: Georg Reimer.

Correspondence: The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt et al. 29 vols to date. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985–.

Endlicher, Stephan Ladislaus. 1836–42. Genera plantarum secundum ordines naturales disposita. With 4 supplements; in 2 vols. Vienna: Friedrich Beck.

Gärtner, Karl Friedrich von. 1849. Versuche und Beobachtungen über die Bastarderzeugung im Pflanzenreich. Mit Hinweisung auf die ähnlichen Erscheinungen im Thierreiche, ganz umgearbeitete und sehr vermehrte Ausgabe der von der Königlich holländischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Stuttgart: E. Schweizerbart.

Mabberley, David J. 1997. The plant-book. A portable dictionary of the vascular plants. 2d edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marginalia: Charles Darwin’s marginalia. Edited by Mario A. Di Gregorio with the assistance of Nicholas W. Gill. Vol. 1. New York and London: Garland Publishing. 1990.

Pauly, Daniel. 2004. Darwin’s fishes. An encyclopedia of ichthyology, ecology, and evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Variation: The variation of animals and plants under domestication. By Charles Darwin. 2 vols. London: John Murray. 1868.

Summary

Gives details of some crossing experiments with Eschscholzia.

Describes the grass Streptochaeta, which FM believes to be a primitive grass.

Relates some observations on maize that are well explained by Pangenesis.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-6549

- From

- Johann Friedrich Theodor (Fritz) Müller

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- Santa Catharina, Brazil

- Source of text

- DAR 76: B34–5

- Physical description

- ALS 4pp † sketch

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 6549,” accessed on 18 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-6549.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 17