From Fritz Müller1 9 September 1868

Itajahy,

Septbr. 9. 1868.

My dear Sir.

I received your kind letter of June 3d and have to thank you also for copies of Dr. Hildebrand’s paper on graft-hybrids of potatoes and of your papers on the illegitimate offspring of dimorphic and trimorphic plants and on the specific difference between Primula veris, vulgaris and elatior.2 All these papers have much interested me. I have united, in the manner indicated by Dr. Hildebrand, a wild uneatable potatoe and Solanum tuberosum; some buds of the latter species fastened on wild potatoes are growing well; the shoots in all respects ressemble to the species (Sol. tuberosum), from which the buds were taken.3 If you should like to experiment on our wild potatoes, you may perhaps have some from Dr. Hooker, to whom I sent some in a box of living plants, despatched lately for Kew by a friend of mine.4

The results obtained by you as to the hybrid-like character of the illegitimate offspring of dimorphic and trimorphic plants appear to me so remarkable and important, that I have planted into my garden some of our dimorphic and trimorphic plants (Manettia bicolor and several species of Oxalis) in order to repeat your experiments.—5

I told you that I found one of our Bignoniæ to be self-sterile, and that 29 flowers of two plants of this Bignonia fertilized with pollen of neighbouring plants yielded only 2 pods, whilst 5 flowers of one of the two plants fertilized with pollen of a plant growing at some distance produced 5 capsules; I afterwards fertilized in the same way three more flowers of the same plant and they yielded three pods.6 I may now add, that the two former pods, both of which withered, before the seeds were quite ripe, contained 7 and 24 good, 13 and 8 bad seeds, whereas 2 of the 8 latter pods contained 46 and 49 good, 3 and 0 bad seeds; in 3 of the pods the seeds had been eaten by insect-larvæ, 3 pods are not yet ripe.— It would be rash to build any speculations on this single case of a monomorphic plant quite sterile with own pollen, very sterile with pollen of some plants, perfectly fertile with pollen with some other plants of the species.7 But I think it will be worth while trying more numerous experiments on this as well as on other self-sterile species; I hope, that this may possibly throw some light on the origin of dimorphism and trimorphism.—

As to the auditory organs of the Orthoptera, the original paper by Siebold was published in “Wiegmann’s Archiv für Naturgeschichte. 1844. Vol. I. pg 56.” An abstract is given in “Siebold’s Lehrbuch der vergleichenden Anatomie der wirbellosen Thiere. 1848 pg. 582.”8 Leydig has added many interesting histological details in his “Lehrbuch der Histologie. 1857 pg. 281.”—9 I see in Gerstæcker’s text-book of Zoology (1863), that those Locustidæ, the males of which are deprived of musical organs (such as Gryllacris, & Schizodactylus), are deprived of auditory organs also.—10

In the few Lamellicorn beetles, which I observed after receiving your letter, I have found no sexual difference as to the squeaking noise, they make.—11

From the seeds of Eschscholtzia, you kindly sent me, I obtained seven healthy plants; one of them has much darker leaf-stalks than all the others.—12

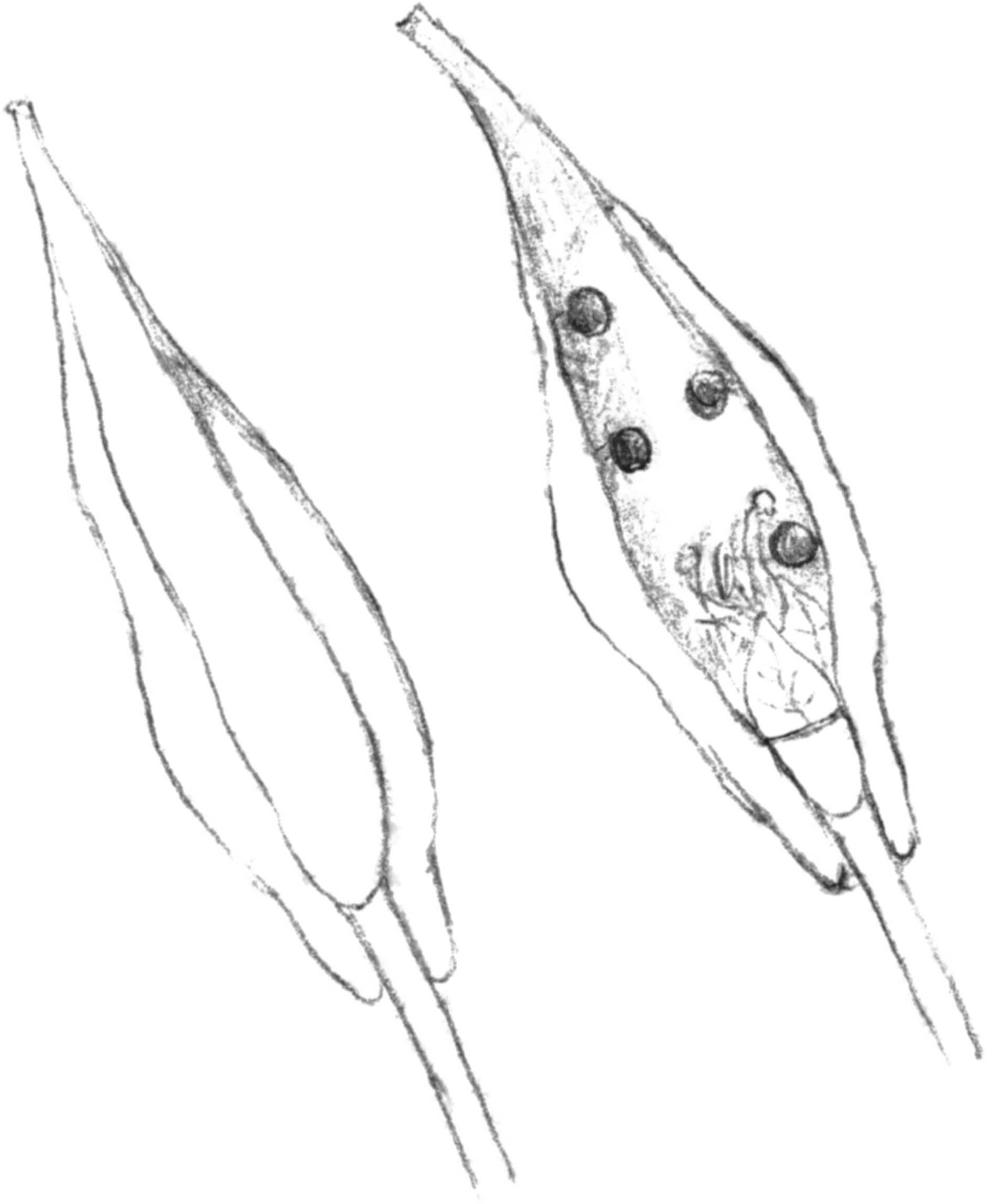

On some plants of a Brassica, which I had received from a Frenchman under the name of “chou chinois”13 I found about a dozen pods, which were much swollen at the base and included one or two small ears of more or less perfectly developed flowers. I mention this monstrosity, because there was a curious coincidence. All the pods including flowers had three valves, one being narrower and inserted higher than the other two.

All the other pods had the ⟨portion missing⟩

Vor einiger Zeit sah ich zwei Häute von jungen Tapiren, die aus dem Leibe ihrer Mutter genommen waren; sie hatten schöne weisse Längsstreifen.14 Bei derselben Gelegenheit sah ich die Haut eines jungen weiblichen Hirsches (Cervus rufus), ebenfalls aus dem Leibe der Mutter genommen; die Haut war zierlich gefleckt und die Flecken in Längsreihen geordnet.15 Ich sah auch früher mal zwei junge Schweine von mattgrauer Farbe mit dunkeln Längsstreifen (zwei oder drei an jeder Seite). Sollten nicht diese Thatsachen uns auf die Vermuthung führen, dass in einer fernen Vorzeit die Vorfahren unserer grösseren pflanzenfressenden Säugethiere (Pferde, Tapire, Schweine, Wiederkäuer) zierlich gestreift oder gefleckt waren? Diese prächtigeren Farben, welche vielleicht durch geschlechtliche Zuchtwahl zustande gekommen waren, mögen vielleicht durch das jetzige bescheidene Kleid ersetzt worden sein in Folge der Nachstellungen von Seiten grosser fleischfressender Thiere.16

Vor einigen Wochen machte ich eine überraschende Beobachtung über die aussergewöhnliche Zahmheit unserer Papageien. Ein Pärchen von Psittacula galatea besuchte gewöhnlich einige kleine Bäume einer Solanum-Art und frass von den unreifen Früchten. Diese Vögel kann man leicht fangen mit einer losen Schlinge, welche an einem Stock befestigt wird. Nun hatte meine älteste Tochter eine Schlinge um den Hals des männlichen Papageien gelegt (er ist an seinem rothen Kopf zu erkennen);17 während sie dies that, sah der Vogel sie mit grosser Aufmerksamkeit und Neugier an. Als sie aber versuchte, den Vogel herunter zu ziehen, riss die Liane, aus welcher die Schlinge gemacht war, entzwei, so dass der Vogel leicht geschüttelt wurde. Nichtsdestoweniger flog er nicht fort, sondern beobachtete weiter aufmerksam die Bewegungen meiner Tochter, welche nun eine neue Schlinge machte, die sie dem Vogel wieder um den Hals legte und ihn herunter zog. Wir hielten nun den Papagei einige Tage in einem Käfig, setzten dann den Käfig unter den Solanum-Baum und öffneten ihn. Aber der Papagei war durch diese Erfahrung nicht vorsichtiger geworden; er wurde mit einer Schlinge von dem Baum wieder herunter geholt mit derselben Leichtigkeit wie vorher, und er hat auch noch weiter den Baum besucht, auf dem er zweimal gefangen worden ist; auch heute habe ich ihn dort mit seinem Weibchen gesehen, welches viel scheuer ist als das Männchen.

Ich habe gesehen, dass ein Urú (Perdix dentata oder Odontophorus dentatus)18 auf dieselbe Art mit einer an einem Stock befestigten Schlinge gefangen wurde. Einige von unsern Vögeln, die nur zeitweise in Gegenden kommen, welche von Weissen bewohnt sind, haben noch gar keine Furcht vor Feuerwaffen bekommen. Ich habe selbst gesehen, dass ein halbes Dutzend Jacutingas (Penelope pipile) eine nach der anderen von demselben Baum heruntergeschossen wurden, und ein Nachbar von mir erzählte mir, dass er vor zwei Jahren von einem grossen Guarajuva-Baum etwa hundert Jacutingen herunter geschossen hätte.19

Der Winter von 1866 war ungewöhnlich kalt, und Jacutingas waren damals von der Serra in so grosser Zahl herunter gekommen, dass in wenigen Wochen ungefähr 50 000 am Itajahy geschossen wurden. Burmeister, der in den Provinzen Rio de Janeiro und Minas-geraes reiste und dessen Beobachtungen im allgemeinen zuverlässig sind, sagt, dass die Jacutinga ein scheuer Vogel sei; wahrscheinlich ist sie in jenen Provinzen schon seit Jahrhunderten mit Feuerwaffen verfolgt worden.20

Bei einer von unsern Maxillarien traf ich letzthin ein merkwürdiges kleines Anhängsel vorn vor der Narbenkammer, dessen Stellung dem merkwürdigen Staubblatt des inneren Kreises entspricht;21 dieses Anhängsel kann man nur bei Knospen und eben geöffneten Blüthen sehen; später löst es sich in eine klebrige Masse auf.... .

CD annotations

Footnotes

Bibliography

Birds of the world: Handbook of the birds of the world. By Josep del Hoyo et al. 17 vols. Barcelona: Lynx editions. 1991–2013.

Burmeister, Karl Hermann Konrad. 1854–6. Systematische Uebersicht der Thiere Brasiliens, welche während einer Reise durch die Provinzen von Rio de Janeiro und Minas geraës gesammelt oder beobachtet wurden. 3 vols. Berlin: Georg Reimer.

Columbia gazetteer of the world: The Columbia gazetteer of the world. Edited by Saul B. Cohen. 3 vols. New York: Columbia University Press. 1998.

Correspondence: The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt et al. 29 vols to date. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985–.

Descent: The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. By Charles Darwin. 2 vols. London: John Murray. 1871.

Forms of flowers: The different forms of flowers on plants of the same species. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1877.

‘Illegitimate offspring of dimorphic and trimorphic plants’: On the character and hybrid-like nature of the offspring from the illegitimate unions of dimorphic and trimorphic plants. By Charles Darwin. [Read 20 February 1868.] Journal of the Linnean Society of London (Botany) 10 (1869): 393–437.

Journal of researches: Journal of researches into the geology and natural history of the various countries visited by HMS Beagle, under the command of Captain FitzRoy, RN, from 1832 to 1836. By Charles Darwin. London: Henry Colburn. 1839.

Leydig, Franz. 1857. Lehrbuch der Histologie des Menschen und der Thiere. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag von Meidinger Sohn & Comp.

Mabberley, David J. 1997. The plant-book. A portable dictionary of the vascular plants. 2d edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Möller, Alfred, ed. 1915–21. Fritz Müller. Werke, Briefe und Leben. 3 vols in 5. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

Müller, Fritz. 1871. Ueber den Trimorphismus der Pontederien. Jenaische Zeitschrift für Medicin und Naturwissenschaft 6: 74–8.

Newton, Alfred. 1893–6. A dictionary of birds. Assisted by Hans Gadow, with contributions from Richard Lydekker, Charles S. Roy, and Robert W. Shufeldt. 4 parts. London: Adam and Charles Black.

Orchids: On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fertilised by insects, and on the good effects of intercrossing. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1862.

Origin: On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1859.

Siebold, Karl Theodor Ernst von. 1844. Über das Stimm- und Gehörorgan der Orthopteren. Archiv für Naturgeschichte 10: 52–81.

‘Specific difference in Primula’: On the specific difference between Primula veris, Brit. Fl. (var. officinalis of Linn.), P. vulgaris, Brit. Fl. (var. acaulis, Linn.), and P. elatior, Jacq.; and on the hybrid nature of the common oxlip. With supplementary remarks on naturally produced hybrids in the genus Verbascum. By Charles Darwin. [Read 19 March 1868.] Journal of the Linnean Society (Botany) 10 (1869): 437–54.

Variation: The variation of animals and plants under domestication. By Charles Darwin. 2 vols. London: John Murray. 1868.

West, David A. 2003. Fritz Müller. A naturalist in Brazil. Blacksburg, Va.: Pocahontas Press.

Whitehead, George Kenneth. 1993. The Whitehead encyclopedia of deer. Shrewsbury: Swan Hill Press.

Translation

From Fritz Müller1 9 September 1868

Some time ago I saw two hides of young tapirs that had been taken from their mother’s womb; they had fine white longitudinal stripes. On the same occasion I saw the skin of a young female deer (Cervus rufus), likewise taken from the womb of the mother; the hide was finely spotted, and the spots arranged in longitudinal rows.2 Earlier I also saw two young pigs of a dull grey colour with dark longitudinal stripes (two or three on each side). Should not these facts lead us to the conjecture that in the distant past the ancestors of our larger herbivorous mammals (horses, tapirs, pigs, ruminants) were finely striped or spotted? Those more splendid colours, which perhaps came about through sexual selection, may have been replaced by the present inconspicuous coat as a result of predation on the part of large carnivorous animals.3

A few weeks ago I made a surprising observation on the unusual tameness of our parrots. A pair of Psittacula galeata commonly visited some small trees of a Solanum species and ate the unripe fruit. One can easily catch these birds with an open noose fastened to a stick. Now my oldest daughter had placed a noose around the neck of the male parrot (which is recognizable by its red head);4 while she was doing that the bird looked at her with great attentiveness and curiosity. But as she tried to pull the bird down, the liana from which the noose was made broke in two, so that the bird was slightly shaken. Nevertheless it did not fly away, but watched with further attentiveness the movements of my daughter, who now made a new noose which she placed around the bird’s neck, and pulled it down. We kept the parrot for several days in a cage, then set the cage under the Solanum tree and opened it. But the parrot had not become more cautious through experience; it was brought down again from the tree with a noose as easily as before, and it has yet again visited the tree on which it has been twice captured; even today I have seen it there with its mate, who is much shyer than the male.

I have observed that an urú (Perdix dentata or Odontophorus dentatus)5 was captured in the same way, with a noose fastened to a stick. Some of our birds which only occasionally come to regions inhabited by Whites have not yet acquired any fear of firearms. I have myself observed a half-dozen jacutingas (Penelope pipile) shot down one after the other from the same tree, and a neighbour of mine told me that he had two years ago shot about a hundred jacutingas out of a large guarajuva tree.6

The winter of 1866 was unusually cold, and jacutingas therefore came down from the Serra in such great numbers that in a few weeks approximately 50,000 were shot on the Itajahy. Burmeister, who travelled in the provinces of Rio de Janeiro and Minas-geraes, and whose observations are generally reliable, says that the jacutinga is a shy bird; it has probabaly already been persecuted with firearms in those provinces for hundreds of years.7

In one of our Maxillarias I recently found in front of the stigmatic chamber a curious little appendage the position of which corresponds to the remarkable stamen of the inner ring;8 that appendage can be seen only in buds and newly-opened flowers; later it dissolves into a sticky mass.... .

Footnotes

Bibliography

Birds of the world: Handbook of the birds of the world. By Josep del Hoyo et al. 17 vols. Barcelona: Lynx editions. 1991–2013.

Burmeister, Karl Hermann Konrad. 1854–6. Systematische Uebersicht der Thiere Brasiliens, welche während einer Reise durch die Provinzen von Rio de Janeiro und Minas geraës gesammelt oder beobachtet wurden. 3 vols. Berlin: Georg Reimer.

Columbia gazetteer of the world: The Columbia gazetteer of the world. Edited by Saul B. Cohen. 3 vols. New York: Columbia University Press. 1998.

Correspondence: The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt et al. 29 vols to date. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985–.

Descent: The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. By Charles Darwin. 2 vols. London: John Murray. 1871.

Forms of flowers: The different forms of flowers on plants of the same species. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1877.

‘Illegitimate offspring of dimorphic and trimorphic plants’: On the character and hybrid-like nature of the offspring from the illegitimate unions of dimorphic and trimorphic plants. By Charles Darwin. [Read 20 February 1868.] Journal of the Linnean Society of London (Botany) 10 (1869): 393–437.

Journal of researches: Journal of researches into the geology and natural history of the various countries visited by HMS Beagle, under the command of Captain FitzRoy, RN, from 1832 to 1836. By Charles Darwin. London: Henry Colburn. 1839.

Leydig, Franz. 1857. Lehrbuch der Histologie des Menschen und der Thiere. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag von Meidinger Sohn & Comp.

Mabberley, David J. 1997. The plant-book. A portable dictionary of the vascular plants. 2d edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Möller, Alfred, ed. 1915–21. Fritz Müller. Werke, Briefe und Leben. 3 vols in 5. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

Müller, Fritz. 1871. Ueber den Trimorphismus der Pontederien. Jenaische Zeitschrift für Medicin und Naturwissenschaft 6: 74–8.

Newton, Alfred. 1893–6. A dictionary of birds. Assisted by Hans Gadow, with contributions from Richard Lydekker, Charles S. Roy, and Robert W. Shufeldt. 4 parts. London: Adam and Charles Black.

Orchids: On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fertilised by insects, and on the good effects of intercrossing. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1862.

Origin: On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1859.

Siebold, Karl Theodor Ernst von. 1844. Über das Stimm- und Gehörorgan der Orthopteren. Archiv für Naturgeschichte 10: 52–81.

‘Specific difference in Primula’: On the specific difference between Primula veris, Brit. Fl. (var. officinalis of Linn.), P. vulgaris, Brit. Fl. (var. acaulis, Linn.), and P. elatior, Jacq.; and on the hybrid nature of the common oxlip. With supplementary remarks on naturally produced hybrids in the genus Verbascum. By Charles Darwin. [Read 19 March 1868.] Journal of the Linnean Society (Botany) 10 (1869): 437–54.

Variation: The variation of animals and plants under domestication. By Charles Darwin. 2 vols. London: John Murray. 1868.

West, David A. 2003. Fritz Müller. A naturalist in Brazil. Blacksburg, Va.: Pocahontas Press.

Whitehead, George Kenneth. 1993. The Whitehead encyclopedia of deer. Shrewsbury: Swan Hill Press.

Summary

Will repeat CD’s experiments on dimorphic and trimorphic plants.

Auditory organs of Orthoptera; stridulation in lamellicorn beetles.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-6359

- From

- Johann Friedrich Theodor (Fritz) Müller

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- Itajahy

- Source of text

- DAR 82: A92, Möller ed. 1915–21, 2: 146–7.

- Physical description

- inc †

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 6359,” accessed on 19 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-6359.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 16