To Asa Gray 31 October [1860]

15 Marine Parade | Eastbourne

Oct 31

My dear Gray

Since I wrote about a week or 10 days ago, we have had such a week of misery as I did not know man could suffer. My daughter grew worse & worse, with pitiable suffering, so that all the Doctors thought we should lose her.1 But the stoppage is over, & she has rallied surprisingly; but whether there is much organic mischief & what the final result will be cannot be known, till the miserable issue is decided. But she is quite easy now, & one comes at last to care only for that;; & we have managed to conceal from her, her extreme danger.— You are so kind & sympathetic that I have not resisted telling you our unhappiness.— We shall not be able to remove her home for several weeks, even if the case is not worse than the Doctors now hope & believe.—

I received this morning your letter of 16th Oct, & forwarded that to Decaisne.—2 Thanks for Atlantic Oct. nor. which I shall find at home; but I have ordered 2 copies for self, so I shall be able to give away.3

How I wish you had time to write on affinities in relation to descent with modification; how well you would do it.— Could you not some time bring it in by side wind in discussing affinities of some group in some of your papers? You have in truth far more, over & over again, done more than you promised in getting my views a fair hearing.—

I have been reflecting about getting, as you suggest, if it can be done, 200 or 250 copies of the 3 articles of the Atlantic reprinted from the Plates in America & sent here.4 Could it be done for 4 or 5 Pounds; I would gladly pay that.— I do not think it would be very material about the paying. But what I do consider all important; is that you would prefix title-page with your name & titles. If you did not object to this, I would post a copy to all the Scientific men I could get addresses of from the Societies. Unless your name was appended, the articles would not, I am sure, be read in England & it would be time & money thrown away. Their merit would not be discovered. But would it not cost you a good deal of trouble to get it done? They might be sent to care of Murray Albemarle St or Williams & Norgate, marked “to be forwarded”.—

I am profoundly contented with your sentence “I think it grows more & more likely that species are derived.” I am grieved to hear about Dana.—5 I enclose sketch about Spiranthes; if you will observe your species, I shd. be infinitely obliged. If a very distinct species, the contrivance will probably differ; as the contrivances are endlessly diversified.— I am not sure that you will understand my rough description, but you will if your species is like ours.— I shall publish on Drosera.—

Yours ever my dear Gray | Most truly | C. Darwin

As You speak of determinate movements for an end in plants I am tempted to give case of Orchis pyramidalis which seems to me pretty.6 The pollinia are attached to connate glands of shape of a saddle, & are suspended in cup of liquid with a moveable lip.—

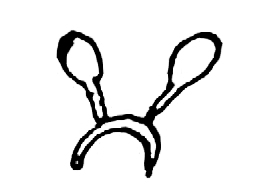

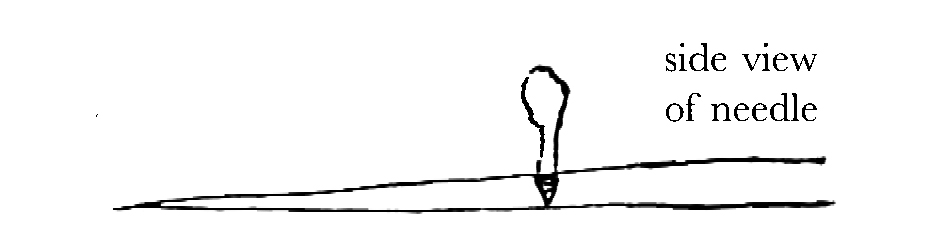

Insert a needle into the nectary, & the lip of cup is moved, & the sticky under surface of saddle sticks to needle & the pollinia are removed. Immediately the saddle is exposed to air (& not whilst under water) the flaps of the saddle curl in & embrace the needle. I had a moth sent me with 3 pollen-masses attached to proboscis & the sender said it was extraordinary how the moth had bored through the sticky glands of some orchis! The movement of the flaps is very conspicuous. At first pollinia occupy this position

(viewed laterally, one pollen-mass behind the other); & if you push needle into nectary of another flower, the pollen-masses do not touch stigmas, which are lateral & double, one on each side of orifice of nectary. But immediately after the flaps of saddle have seized round the needle, another movement commences, & the pollinia move downward, nearly parallel to needle & the two diverge from each other.

(viewed laterally, one pollen-mass behind the other); & if you push needle into nectary of another flower, the pollen-masses do not touch stigmas, which are lateral & double, one on each side of orifice of nectary. But immediately after the flaps of saddle have seized round the needle, another movement commences, & the pollinia move downward, nearly parallel to needle & the two diverge from each other.

Now if if you push needle into nectary, the pollen-masses exactly hit the lateral stigmas & leave pollen-grains on them. The seat of this latter movement, which is always in one direction, lies at the junction of the footstalk of pollinia & the saddle.

[Enclosure]

Spiranthes autumnalis 7

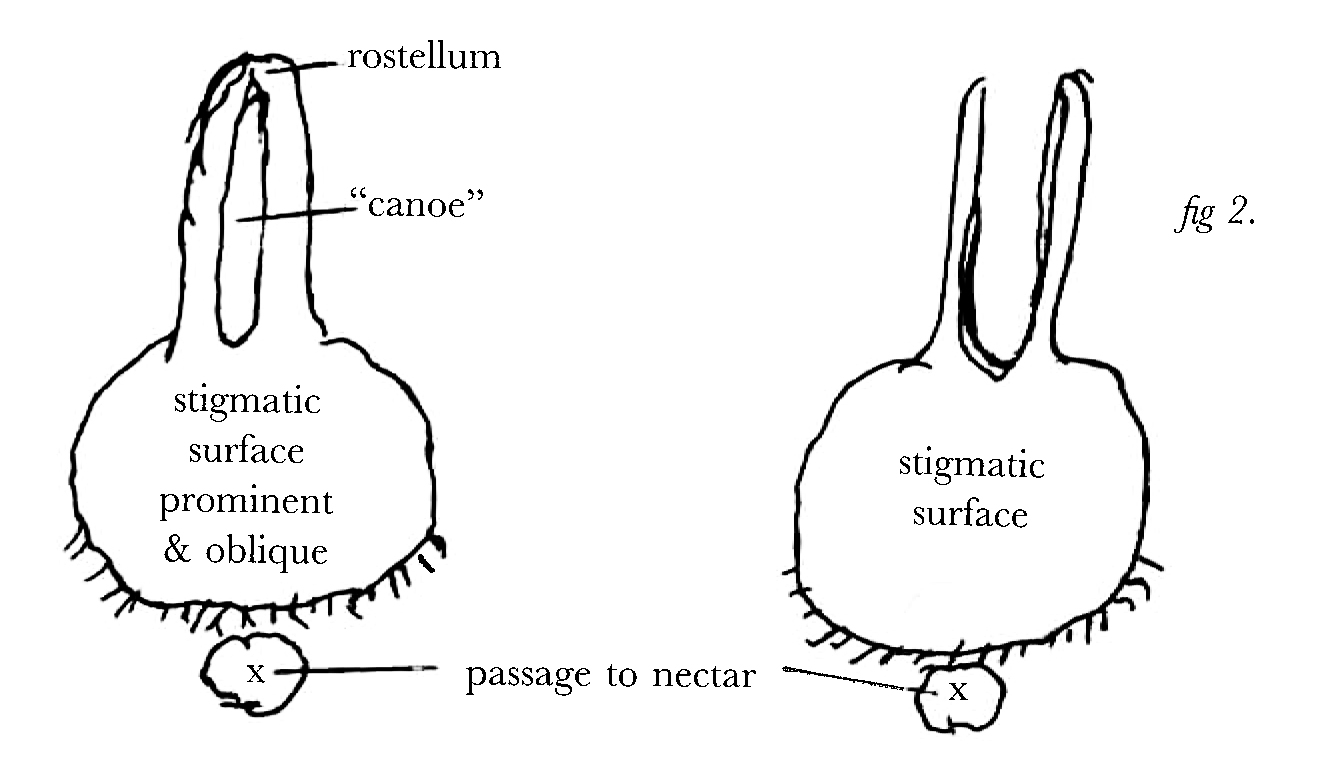

(1) In rather early bud the anthers open & press pollinia against back of rostellum

(2) Back of rostellum opens in early bud & a viscid substance glues the pollinia to the back of the rostellum or strictly to the bottom of what I call the “canoe”.8

(3) When the flower first opens the rostellum is not ruptured on the front surface, (ie on surface above the stigma) Within the substance of the rostellum a brownish hard object can be seen, which is of the shape of a “canoe”, pointed at both ends, & standing vertically up, parallel to longer axis of rostellum. The bottom of canoe, as stated, is already glued to the pollinia.— The front & concave or hollow side of the canoe is filled or loaded with very viscid substance, which sets hard in less than a minute when exposed to the air. The concave side of the canoe is, as stated, covered, when flower opens, by the membrane of the rostellum.—

(4) Now if front surface of rostellum be touched longitudinally most delicately by a needle, (or exposed to vapour of chloroform) it instantly splits longitudinally its whole length, & the needle comes into contact with the viscid matter within the canoe. The canoe embedded in the rostellum becomes firmly glued to the needle; & the bottom of the canoe is already long since glued to the pollinia. Hence when the needle is withdrawn the canoe & pollinia are all withdrawn together. The rostellum is then left in the state rudely represented by fig 2. All the flowers which have been visited by insects are in this condition. Change the needle into the proboscis of insect, & you will see how fertilisation is effected. The pollinia become attached nearly parallel to proboscis; & the insect visiting a second flower is sure to strike the apices of the pollinia against the obliquely projecting viscid stigma.— If you poke thin culm of a grass down to nectar & withdraw it without bending, you will not withdraw the pollinia; but if before you withdraw it, you bend the culm so that its bowed or convex surface touches the rostellum the pollinia will generally be withdrawn. Moths in curling up their probosces after sucking perform this action; & I go so far as to believe, whole structure of flower is made in relation to this mode of withdrawing proboscis!!!

Footnotes

Bibliography

Correspondence: The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt et al. 29 vols to date. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985–.

Orchids: On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fertilised by insects, and on the good effects of intercrossing. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1862.

Origin: On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. By Charles Darwin. London: John Murray. 1859.

Summary

Talks of getting copies of AG’s Atlantic Monthly articles for distribution in England.

Describes the pollinating mechanisms of Orchis pyramidalis and Spiranthes autumnalis.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-2969

- From

- Charles Robert Darwin

- To

- Asa Gray

- Sent from

- Eastbourne

- Source of text

- Archives of the Gray Herbarium, Harvard University (45 and 124a)

- Physical description

- ALS 8pp

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 2969,” accessed on 19 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-2969.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 8