From William Charles Linnaeus Martin [1859–61]1

Comments on Mr. Darwin’s Grand Theory= (touching Misuse)

Mr. Darwin p. 338—says—“Agassiz insists that ancient animals resemble to a certain extent the embryos of recent animals of the same classes;—or that the geological succession of extinct forms, is in some degree parallel to the embryological development of recent forms. I must follow Pictet & Huxley in thinking that the truth of this doctrine is very far from proved— Yet I fully expect to see it hereafter confirmed, at least in regard to subordinate groups which have branched off from each other in comparatively recent times For the doctrine of Agassiz accords well with the theory of Natural Selection”.—2

Now I cannot help thinking, from the little knowledge I have, that there is a glimpse of truth in the theory of Agassiz—& well indeed does it accord with the views of Mr. Darwin, who supposes improvement, by Nat. Selection in the multitudinous assemblage of Organic Beings.— The tendency is to progress by development,—Natural selection always benefitting the living creature.— The forms, which stop short in the progress of divergence & adaptation to the struggle of Life, become rarer & rarer & at last extinct.—

Among the surviving wrecks of ancient Life he reckons the Blind=Fish, Amblyopsis—& the Proteus anguinus (which is confessedly a sort of semideveloped Tadpole,)—as is the Axolotl,3—& some others— Still they do well for their destined abode, & mode of life—whatever hereafter may become of them.— Were the caves of Carniola4 destroyed by any agency—& the deep waters in its natural dungeons dried up, or poured out over the land & so into the rivers, with all the Proteus train, what would be the result— would the survivors of the catastrophe put on new forms—or would all perish— if the latter & circumstances favoured not fossil preservation, they would pass away, & leave no trace hereafter of their once having existed— Has this not often been the case?—

—At p: 188—Mr Darwin speaks of that marvellous organ the Eye— & he supposes it to be under the jurisdiction of natural selection.— “We must suppose that there is a power always intently watching each slight accidental alteration, which under varied circumstances may in any ways or in any degree, tend to produce a distincter image— We must suppose each new state of the instrument to be multiplied by the million & each to be preserved till a better be produced, & then the old ones to be destroyed—” p: 189.—5

Look now at the beautiful eyes of the frog— look at those of the Tadpole— Look at the beaming eyes of the gazelle— reflect upon them in the embryo.—

But is there not an arrest in development balanced by & subervient to mingled contingences— The eye of the mole is not that of the eagle,—but what upon the Principle of Natural Selection is to prevent it so becoming;— Has the eye of the degenerated for want of use—6

It seems strange to us that carrying out his theory of Progress, according to the laws of Natural Selection Mr Darwin should entertain the views he appears to do, in his Chapter on Use & disuse.—7 Might he not have have used the Term, “Non development from an embryotic or semiembryotic state”, the contingencies of existence not needing the operation of the selective power inherent in the nature of organic beings?—

After reading so much on the benefits conferred by Natural Selection on organic beings, & their consequent advancement in those qualities which tend to render them more & more capable of maintaining the Struggle of Life, it occasions some surprise to learn, that under certain circumstances deterioration & unfitness are the result of certain casual circumstances.— For example,—that the non use of wings, once fully developed, entails a progressive reduction in the wings of succeeding generations until at length they become mere rudimentary appendages—8 Per contra—Is it not that the rudimentary winged birds are in state of progression,—& nearer the unknown primeval source, than the fully winged birds— And if natural selection has attended more to the legs than the wings, is it not because the latter were rather neglected & left under arrest, the whole force for the benefit of the race being directed to the other limbs—?—

Birds tenanting oceanic islands are usually great flyers.— But the Dodo & Solitaire feeding upon the shore had no need of developed wings, & the force of Nature was elsewhere directed.— The non=use of a bird’s wing is the result not the cause of a rudimentary condition & on Mr. Darwin’s principles a gradual organic development ought to take place till the bird is capable of flight.— Is it not the strife for wings that we see in the Apteryx the Cassowary, the Rhea, the Emeu &c

How many wingless birds have passed away— New Zealand & Madagascar present us with their fossil or semifossil remains, & but for these who would have dreamed of their having existed?— Does not this shew that wingless birds were the earliest or among the earliest of the descendants of the unknown primeval root?— Mr. Darwin says, “As Professor Owen has remarked, there is no greater anomaly in nature than a bird which cannot fly.”9 It is bold to differ from so great a philosopher—but we venture with submission to think the contrary— It is because we usually see birds with wings & are accustomed to consider birds as feathered flying creatures, that we come to settle it as fact that birds are essentially winged—(albeit in some the wings are fitted only for aquatic progression).—

But were we accustomed to see Birds without wings, or only with rudimentary wings (& great is the number of such) should not think a bird of flight an “anomalous” creature— Among mammalia do not the Bats & Galeopitheci startle us?— However they acquired flying membranes (or as in the case of certain squirrels & Phalangers) ample parachutes, certain it, that as these organs are beneficial, so they do not deteriorate,—perhaps improve.10 And when we contemplate a Bird without wings, instead of attributing their loss to Disuse may we not rather on Mr Darwins theory believe that something has produced an arrest, & that the time has not yet arrived for their full development— With respect to the malformed creatures of domestication,—as upright or Penguin Ducks,—otter sheep,—two legged Pigs, & the like11—we cannot bring them into the argument— they are artificial not natural beings—although they may propagate their breeds.—as do Lop-eared Rabbits—Fowls destitute of a tail, or with reversed feathers, or with silky plumage & a black periosteum.—12

Turning for a moment to Insects—some of which as Scarabæus, Ateuchus &c, want the anterior tarsi,—while others, with undivided Elytra have the membranous wings in a more rudimentary condition, is it necessary for us to have recourse to non use as a cause?=13 Is non=use so influential?— it may affect the Individual—but can it affect a whole race— And after all, what induced non=use in the beginning?— Deficiency of development,—to be modified & bettered by the agency of Natural selection—at all events as soon a maze of contingencies call for the operation of this principle Of course we follow Mr. Darwin’s Theory.—

With respect to the eyes of moles & such like underground creatures—fitted for their habits,—natural selection is not likely until, circumstances gradually operate to do more than make them efficient delvers.— In the case of the Cave rat we verily believe that if a nest of blind young were reared in a room their eyes would be day seeing or twilight=seeing—& in a few generations as good as the eyes of rabbits or hares.—14

From what has been said—& it is impossibble here to enter at large into the subject, it will be seen that we hesitate to accecpt the theory as to the permanent influence of non use, in the establishment of Imperfection.— It may cause imperfection, nay it does so, for our rabbits cramped up in small hutches, wherein they have been born & bred are very small & feeble in the hinder limbs— But turn them out into the coppice or upon the heath, there let them breed & then see if their young are not as able with their hinder extremities as any of the old true wild stock around them.—15 We must be pardoned then, if we cannot subscribe to the opinion that disuse unites the elytra of beetles into one shard,—curtails their wings & necessarilily renders them creepers under stones—16 Are we not changing cause & effect?— We must not forget that the females of many moths are wingless—as is the female of the glow=worm—that the Gnats which dance in the air are males,—plumed, but not armed with a keen suctorial instrument, as are the females— That the male crickets & grasshoppers alone are stridulous,—the females wanting the necessary apparatus— Has disuse removed the wings from the moths in question—the piercer from the male Culex,—the stridulous apparatus from the female Cricket— If this theory of disuse or Non=use be sound, surely it ought to apply in such cases—no less than in others.— Can Deterioration be consistent with the Great Principle of Natural Selection.—

Let us pass over these points, & again revert to Wingless or rather Brevipennate Birds— Had we only seen such—& we suspect (on Mr. Darwin’s system) that such were the primeval creatures out of which Birds were fashioned by almost insensible stages,—should we not regard— should we not have regarded (supposing our existence in those remote periods of times,) a winged bird hovering in the air as a terrible monster.—

Does it follow that all birds have advanced pari passu?— May not many an arrests or stoppages have occurred from a combination of contingences, leaving vast numbers of birds, not advanced up to the mark in alar development, whose brevipennate descendants, surviving the lapse of Time remain to tell a story of strange mutations & undreamed of phases on the surface of our planet, from the Silurian epoch, even to the present— But alas we we know not the language—no nor can we decipher the mystic hieroglyphics,—the lithoglyphs of a world gone by.—

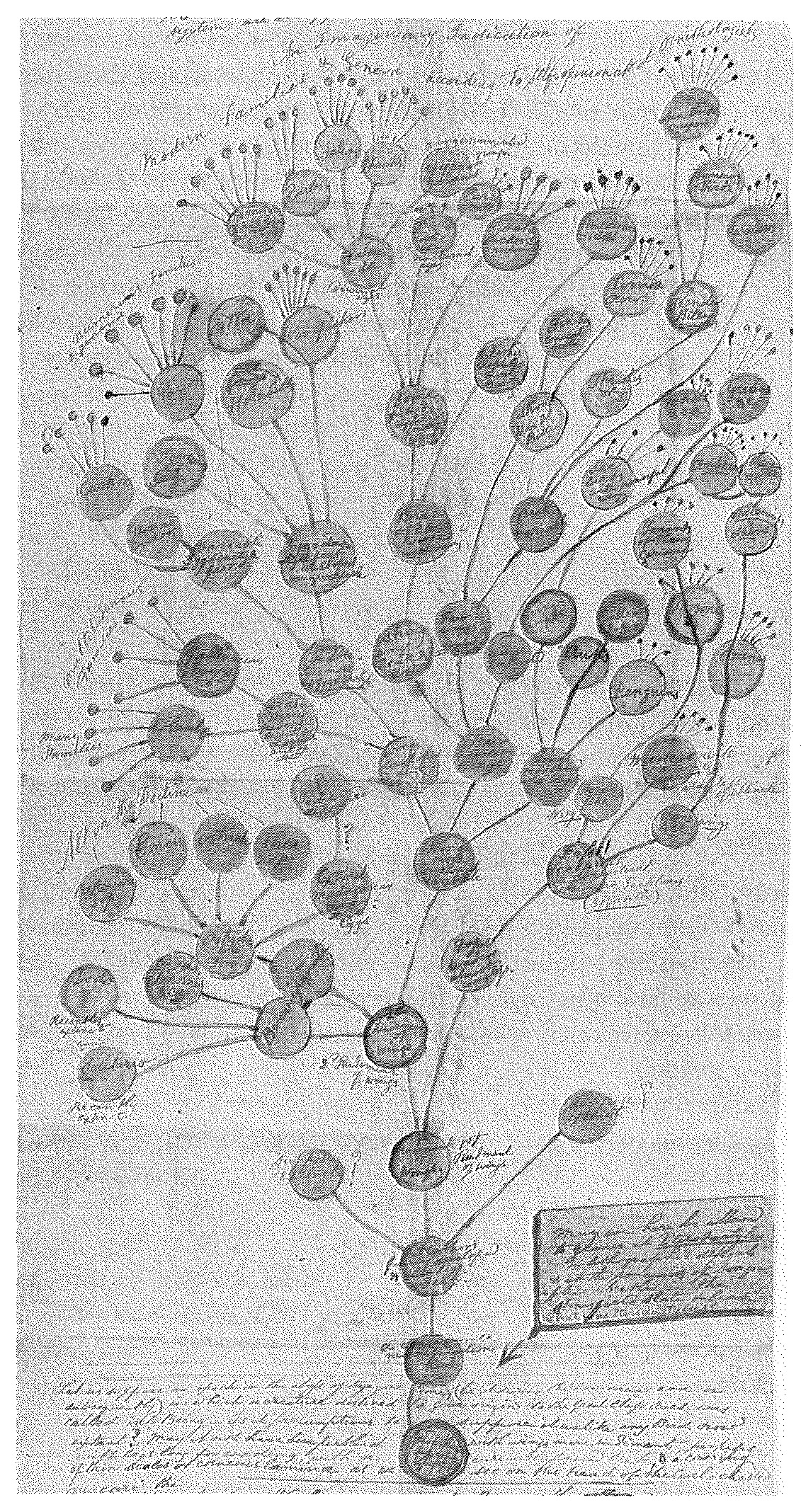

But it is time to conclude a paper perchance unworthy of consideration= Fearing indeed that this may be the case we will not draw it out to a tedious length—at the same time, we have ventured upon a sort of imperfect & very crude diagram, explanatory of our views, Birds alone being its subject— What bears upon one great division of Organic Being, bears, so we venture to opine, upon every other.—

W. C. L. Martin.—

[Enclosure 1]

As may easily be perceived, this is a very rude “Ebauche” a mere rough sketch, (on rough paper), intended to convey an imperfect, & as yet, not maturely studied idea of the development of the leading forms of birds divaricating from a primeval, extinct, & of course unknown root.— For its roughness & imperfection I must apologize,—indeed I ought to have recopied it—but I am not in health—& every trifle is a labour— Should you however, deem this rough sketch not altogether worthless, I will copy it upon more sightly paper, with such improvements & alterations as further reflexion may suggest.—

I throw the terrestrial brevipennate Birds on one side,—the brevipennate & finwinged aquatic birds on the other side,—as diverse branches from the great stem— Birds are not related to each other simply because they are brevipennate—

I suppose each circle (or most of the circles) to represent a group which in the wear of time has proved its stability & contended successfully against contingences in the great struggle of Life— I suppose them to have given off successors, still better fitted for this struggle according to the alteration of influencing conditions, & taking the place of their effete predecessors, and so the progression of change & development as I concieve to go on—group succeeding group—& branching into families & genera, often multitudinous & complex in their affinities—till at last we come to the artificial families & genera of modern ornithologists, whose systems are contradictory & based upon grounds often untenable—seldom philosophical— Thus we have the fanciful systems of the Trinarians, the Quinarians, the upholders of representation17—& so on to Prince C. Lucien Bonaparte, Gray, & others,— strenuous maintainers of their own systems, & each system at variance with every other.—18

Between the rude circles I suppose a long but variable period to intervene—a period mostly perhaps to be measured by ages—geological ages,—for the modifications must be slow— Between these circles I have placed nothing—but the circles represent forms of longer or shorter duration— The small dots, like flower stamens, convey an idea of the ornithological multitude of families & genera—which please modern naturalists & look well on paper, with the appendix of their names to the genera they would fain establish— Great is the rage for genus making— I have known the male & female of an Ortyx (American Quail) made not only into two species, but each into the type of a distinct genus—(Vigors)19—& similar blunders are constantly occurring—

It will be easily percieved that I have no great respect for any ornithological system as yet promulgated— Not one with which I am acquainted but is a baseless fabric—built up by caprice, & fleeting opinion— In my rude sketch I aim at none—& follow none— My object is to elucidate the great Theory of natural selection, & to shew that the rudimentary condition for wings does not arise from Disuse but is one of Partial or arrested Development perhaps necessitating at no distant date the extinction of the survivors of a wingless multitude some of whose relics have been recently brought to light;—while those of others will perchance never be recovered.—

[Enclosure 2]

No two Ornithologists maintain a similar system; their systems are all opposed to each other,—& capriciousness reigns throughout.—

An Imaginary Indication of Modern Families & Genera according to self-opinionated Ornithologists

[Transcription]20

Monstrum informe ignotum21

a considerable modification here May we here be allowed to glance at Pterodactylus in lithographic deposits22 & at the remains of Dragonflies & beetles in the stonesfield slate & lias. What was Pterodactylus?

–Feathers fairly developed also legs & beak

—suppose extinct?

—1st Rudiments of Wings

—–2d Rudiment of Wings

——Brevipennate

——–Solitario23 Recently extinct

——–Dodo Recently extinct

——–Moas. Dinornis & ca

——–Ostrich like Forms

———Cassowary 2 sp.

———Emeu

———Ostrich

———Rhea 2 sp. All on the Decline

——–Extinct Madagascar Forms—Huge Eggs

———To be discovered?

——Wings more developed Variable

——–wings developed Legs ⟨variab⟩le

——— Grain & Berry feeders. Insects & Larvæ part of diet

———– Columbæ

———— Many Families

———– Gallinaceous Groups

———— Multitudinous Families

——— Wings variable—Toes more legs zygodactyle

———– Variable Zygodactyle feet

———— Cuckoos

———— Ground cuckoos

———– Zygodactyle feet developed wings variable

———— Toucans

———— Parrots

————– Numerous Families & genera

———— Hornbills

———— Woodpeckers

————– Sitta

——–[Fair] available wings

———strong wings, Beak & Feet

———–Birds of Prey. some insectivorous

————Some fish & reptile feeders Insects also

————–Falconidæ diurnal eyes

—————abnormal Birds of the Falcon group

—————Eagles

—————Falcons

—————Hawks

—————Gypogeranus a very circumscribed group.24

————–Owls Hawk-like Nocturnal eyes

—————Eared owls

————–Goat-suckers nocturnal

————Fishes Reptiles Insects Beak strong

————–Halcyonidæ

———Fair wings Pointed Beak

———–Strong Hard Bill

————Finches Conical beak

————Corvidæ Crows

———–Beak variable

————Thrushes &c

————–Slender Billed warblers

—————Sunbirds Creepers

—————Humming Birds

————Swallows

———wings contracted

———–Grebes &c

———–Anseres

————Phaeton &c

——–Wings modified also legs

———wings ample

———–Sea birds with powerful wings

————Petrels &c

———Auks

———–Guillemot Puffin

———Penguins

—–Fossil Waders almost wingless

——Fossil footprints Connecticut Permian Sandstones (Gigantic)

——–Heron-like Wings

———Herons

———–Tenants of Plains Cariama

——–Waders with Powerless wings wingless Gallinule

——–Crane-like. wings

———Cranes

———–Balæniceps & others

—suppose extinct?

Let us suppose an epoch in the abyss of bygone time, (be it during the Devonian era or subsequently) in which a creature destined to give origin to the great Class Aves was called into Being— Is it presumptuous to suppose it unlike any Bird now extant? May it not have been purblind with wings mere rudiments, perhaps with legs long for wading, with a curiously formed beak, & a covering of thin scales or corneous laminæ as we see on the head of the Curl-crested aracari, the hackle feathers of Sonnerats Junglefowl & on the back of the young ostrich. After a long lapse of time may we not suppose these corneous laminæ to be resolved into a shaft & barbules more or less close, & rigid, & so on by degrees till true plumage is acquired?

We have no definite Proof of the existence of Birds or Mammalia during the long long travel of Time, whilst the Devonian & Silurian strata were in process of formation

Nevertheless, Red & warm-blooded vertebrata may even then have existed, few, strange, undreamed of by the Naturalist—perhaps so unlike any thing which we now see, as to startle imagination could they revisit our planet.

Devonian & Silurian Transition Formations.

Devonian. Plants—Corals, Crinoidea, mollusca shelled—Cephalopoda

Crustaceans—Trilobites. Fishes &c—occasional layers of coal, with [one word illeg] impressions.—

Silurian. Corals—Mollusca—Trilobites, Crinoideæ, Spirifers, Orthocerata

Fishes &c Strata of marine origin—

Volcanic & Hypogene Primary Rocks We here lose all positive proof of the existence of Organic Beings, but it would be rash to fix the first creation of Plants & animals at the precise point where our retrospective knowledge happens to stop.—

CD annotations

Footnotes

Bibliography

Desmond, Adrian. 1982. Archetypes and ancestors: palaeontology in Victorian London, 1850–1875. London: Blond & Briggs.

Gray, George Robert. 1841. A list of the genera of birds, with their synonyma and an indication of the typical species of each genus. 2d edition. London: Richard and John E. Taylor.

McOuat, Gordon R. 1996. Species, rules and meaning: the politics of language and the ends of definitions in nineteenth century natural history. Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science 27: 473–519.

Ospovat, Dov. 1981. The development of Darwin’s theory. Natural history, natural theology, and natural selection, 1838–1859. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Seeley, H. G. 1901. Dragons of the air. London: Methuen & Co.

Stevens, Peter F. 1994. The development of biological systematics: Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu, nature, and the natural system. New York: Columbia University Press.

Winsor, Mary Pickard. 1976. Starfish, jellyfish and the order of life: issues in nineteenth-century science. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Summary

MS of a paper called "Comments on Mr Darwin’s grand theory", which generally supports CD but proposes that present flightless birds are primitive. Paper supplemented by a diagram showing the phylogeny of birds.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-13827

- From

- William Charles Linnaeus Martin

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- unstated

- Source of text

- DAR 171: 56/1–15

- Physical description

- AmemS 15pp, sketch †

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 13827,” accessed on 19 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-13827.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 13 (Supplement)