From Anthony Rich 1 July 1879

Heene, Worthing.

July. 1. 1879.

My dear Mr. Darwin,

If I had had my “Chesterfield” at my fingers’ ends, or had paid befitting attention to the Proprieties, I should have written to you long ago to say that I had received a set of very pretty photographs from your son at Chatham, and to thank you for the interest you made with him in my behalf.1 I lost no time, however, in making my acknowledgements to him. When I was at Bettwys, (now somewhat about twenty years since) I remember that an artist (with a now forgotten name,) and a chemist, (James of Pall Mall,) came down there to try if the sun could be utilized for the purpose of taking landscapes; which up to that time had never been accomplished. The art was then termed Daguerreotype, not Photography; and the efforts of those two gentlemen were, I believe, only partially successful; for the results and processes were preserved in mysterious secrecy.2 To think of what was accomplished at that time, with these views on the table before me, is almost like passing clean out of one lifetime into another: Perhaps, when another twenty years are passed, the Sun will have learnt to paint as well as he now draws—who knows?—.

I have been much puzzled of late to explain to myself the conduct of a lot of starlings who come to feed upon my lawn, fourteen or sixteen head at a time, some old and some young, and a like number of each— The old birds occupy themselves in seeking grubs and worms, which they duly deliver as soon as found to their young companions, who are I imagine the nestlings of the present season, sufficiently grown to run and fly well, but not yet strong enough of beak to struggle with a worm in its hole. Each old bird has a single young one in attendance upon it; and only a single one; to which alone it delivers its finds—3 Now my perplexity lies in this: It is inconceivable that each of those seven old birds have only hatched out a single offspring this season;—and therefore many of the old ones must be engaged in nursing children not their own— So that the only interpretation that I can put upon a proceeding which seems contrary to the usual course of nature, is to suppose that birds which live in flocks, as distinguished from such as pair or live isolated, are “communists”, sharing together the toils and gains which ensue in their struggle for existence, as some insects do.—

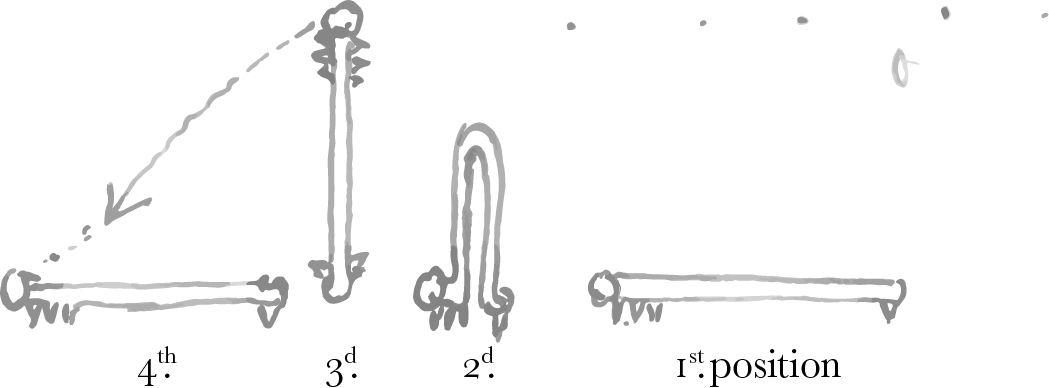

That word “insect” calls to my remembrance another matter which attracted my attention this Spring; and if I had the good fortune of living within a walk of you I am not certain that you would not have had the misfortune of listening to the narrative long ago— It has reference to a drab coloured caterpillar which lives in ivy; and more especially his peculiar method of locomotion. The one upon the ivy branch my gardener brought to me was about an inch and a half long; but I do not think that he had then attained his full growth, as it was early in the spring when I found him: He has no legs; only a couple of nippers at the nether end, one on each side; and six similar ones close behind his neck, three on each side of it.4

When he wants to advance he proceeds to execute three distinct movements. He first brings his nether end up to his neck so that the entire length of the body forms a loop upright;— he then loosens his head piece from the branch, and shoots it with extreme rapidity, bolt upright, as if he was going to leap into the air, but was held back by his tail clips— then he falls forward, like a dead man, and comes down upon the branch just one length of his entire body in advance of his original position.

That seemed to me such an unusual way of progressing that I thought I would mention it to you the first opportunity I had of doing so; my excuse being that caterpillars which live in ivy might very generally escape observation.—

I forgot to mention a droll piece of conduct by one of the young starlings to its parent natural or adopted. When the old bird did not find a worm as readily as the young gourmand required it young greedy, kept drumming with its beak upon the rump of the old one, from behind; and that drove the foraging parent onwards to a wider birth and pastures new— It reminded one of an infant kicking and thumping its nurse when it wanted its luncheon or supper— In truth the whole proceeding was exceedingly droll, and entertaining.—

My conscience hints that that epithet will not apply to this long straggling letter— But to make excuses will only increase the evil, and encroach still further upon your time so much and so well occupied as it is: Please then to forgive the infliction; and permit me to transmit through you my respects to Mrs. Darwin while I sign myself | Very sincerely and faithfully yours | Anthony Rich

Footnotes

Bibliography

Stanhope, Philip Dormer. 1774. Letters written by the late Right Honourable Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield, to his son, Philip Stanhope, Esq; late envoy extraordinary at the court of Dresden: together with several other pieces on various subjects. 2 vols. London: J. Dodsley.

Summary

Starlings seem to share their food. Are they communists as they struggle for their existence?

Describes movement of a caterpillar.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-12130

- From

- Anthony Rich

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- Worthing

- Source of text

- DAR 176: 136

- Physical description

- ALS 8pp

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 12130,” accessed on 19 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-12130.xml