From Edward Blyth 24 February 1867

24/2/67—

My dear Mr. Darwin,

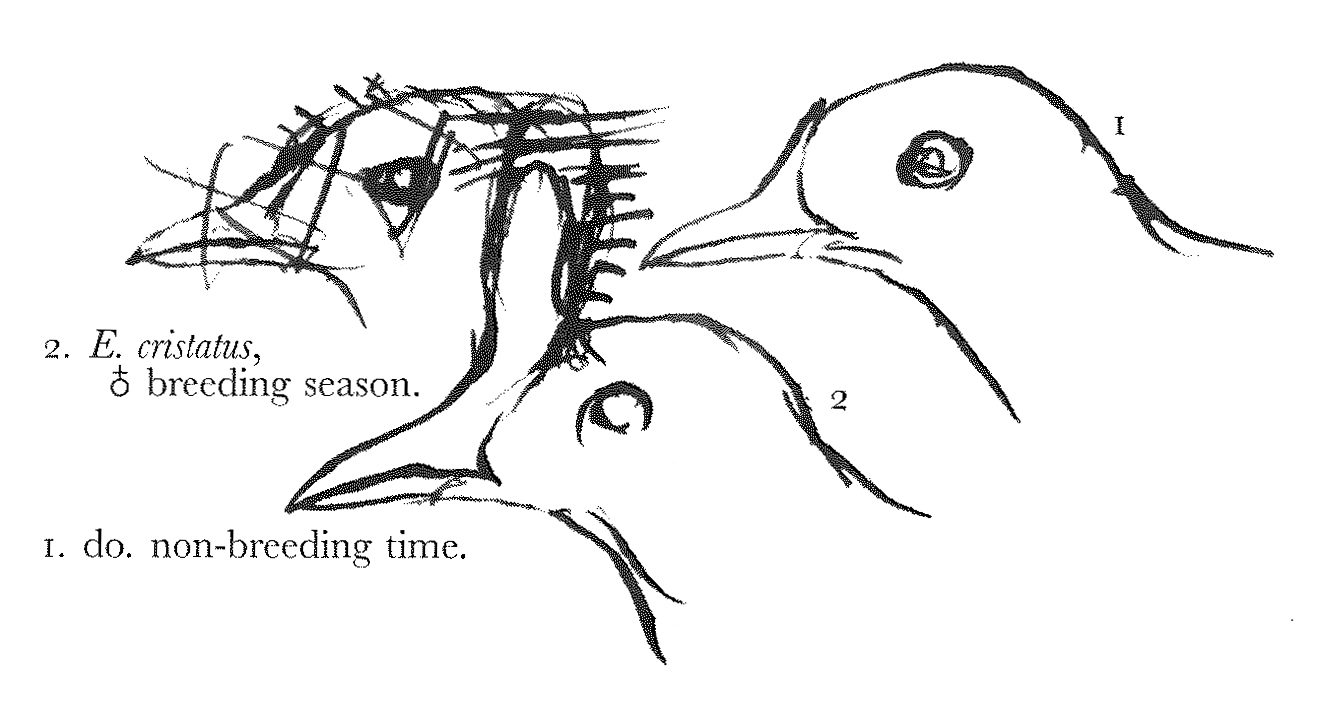

I wish that you could write me word that your bodily health is less precarious, & that the cheerful influences of the coming spring are likely to have a beneficial effect. The remarks of mine which you refer to on the sexual plumage of birds, I cannot recal to mind, & perhaps therefore you would not mind sending them to me, to be returned when I have looked them over.1 It is true that in the bustards the seasonal adornment in the breeding season is peculiar to the male sex, but I want more information about the ruff of the houbara bustards. In the Bengal floriken and likh (Otis deliciosa & aurita), the seasonal change is considerable, & confined to the male, which is smaller than the female. In the little bustard (O. tetrax) the sexes are alike in size, & the male only undergoes great seasonal change of colouring.2 In O. tarda the male is larger, & he alone shows the long moustachial plumes, besides having the gular bag, which I have recently seen (unequivocally developed) in a fresh specimen. The large bustards of the division Eupodotis have also the male larger, & no other secondary sexual difference that I know of, except the gular bag in O. Edwardii, as stated by Sykes & Sir Walter Elliot.3 Now in all the plover and sandpiper series (with one exception) the seasonal change of colouring is common to the two sexes. The exception is the ruff, which alone has the male larger, for in the others I think the male is constantly smaller, & sometimes very conspicuously so, as in Numenius lineatus, and Limosa ægocephala. The seasonal adornment of the ruff is most remarkable (& I am not sure whether or not it is analogous to that of the ruffed bustards—Houbara); but most reeves also, undergo a certain amount of change, with sometimes a slight indication of the frill, the feathers composing which being not much longer than the rest.4 Now the ruff is polygamous; & I suspect that the Kora (Gallicrex cristatus) is also polygamous amongst the Rallidæ. Here again the male is larger, & undergoes a remarkable seasonal change of colouring, which the female does not, besides the development of the frontal caruncle.5

In this bird the male becomes very deeply tinged with dusky cinereous in the breeding season, & the frontal caruncle is coral-red; after breeding the latter shrinks into a small flat acuminated shield, & the bird moults back into the olivaceous plumage of the female, assuming the dusky colouring afterwards by a change of colour in the same feathers. From Wolf’s figures of the weka rail of N. Zealand (Ocydromus), I am led to suspect that this species undergoes a similar change of hue, & probably in the male only.6 In the gulls and terns that assume a breeding plumage, the latter is common to both sexes, e.g. the hoods of the Xema gulls, and the black pileus of many terns. In Hydrochelidon indica (Stephens, hybrida, Pallas, [leucoparius], Tem.), there is a much greater amount of seasonal change in both sexes, and the abdominal region becomes black, whereas in Sterna melanogaster the same part is permanently black; in the black terns (Hydrochelidon fissipes & leucoptera) the seasonal change attains its maximum among the Laridæ; & about the minimum, where there is any change, in L. canus. 7

You ask if I can think of any true carnivora amongst the mammalia in which there is a sexual diversity in the canines.8 Very decidedly in the walrus, on the extreme limit of the order; & you should look to the southern hemisphere seals (Otaria, &c). I have an impression that there may be a difference in the sea-elephant (Morunga), but it may only be proportionate to the size of the skull. The proboscis of Morunga is, if I mistake not, said to be a sexual distinction, & how about the hood of the monk-seal? The only secondary sexual difference I can remember among the terrene carnivora is the mane of the lion.9

In hollow-horned ruminants, there are never upper canines; in the camels & llamas these are much larger in the males; & in the cervine ruminants peculiar (whenever they occur at all) to the males, in which they attain so remarkable a development in the muntjacs, the chevrotains, and the musks (the two latter being hornless).10

In the anthropoid apes the canines are more developed in the male sex, but hardly so (at least disproportionally) among other Quadrumana. One of the most remarkable instances is that of the narwhal, & remember also Mastodon ohioticus.11

Most (if not all) of the deer shed two coats twice annually, having a distinct summer and winter vesture, generally very different in colouring; & I can recal no marked sexual difference of colouring, though the males of many are darker when fully adult, as C. axis, & C. Duvauceli. 12 But in many the males have a considerable nuchal ruff, & the larynx is tumid at the rutting season.

In the bovine and antilopine series (i.e. the sheath-horned ruminants generally) the coat, I think, is never shed more than once in the year, & there is no seasonal enlargement of the larynx, for that of Antilope gutturosa is tumid permanently. In several the adult males are black or blue-grey where the female is brown, & in such species the castrated male resembles the female in colour, e.g. for certain, Ant. cervicapra, Portax pictus, & Bos sondaicus. In the first the black colour disappears after the rutting season, & in fact indicates that the animal is must, as termed in India.13 The sable antelope (Aigoceros niger) has also a permanently black male; & probably the new Cobus maria, from what Sir H. Baker told me; & I feel satisfied that the long-lost Aigoceros leucophæus (as supposed) is no other than adult male A. equinus, coloured like mature male Nil-gai!14

Returning to birds, among what I must call the Parridæ (which are allied to the plovers and not to the rails), the Hydrophasianus sinensis undergoes, alike in both sexes, an extraordinary change of plumage in spring; whereas the Metopidius indicus (& its immediate congeners doubtless) undergoes no vernal change; but the juvenile plumage is very different from the adult, & has been erroneously considered the winter dress.15 In Hydrophasianus there is scarcely any difference between the juvenile and the mature winter plumage. This is a remarkable difference in birds otherwise so nearly allied.

I must see C. Vogt’s paper you allude to.16 I want to get at good descriptions & figures of the unimproved races of domestic animals, especially of sheep just now. Bentley wants me to publish in a volume my essays on Wild Types, which I should like well enough to do, in a rather more scientific manner; but I do not wish to interfere in any way with your promised volume, & would rather supply you with any information I may have.17 As for sheep, I now see clearly—more so than when I penned the article on sheep now publishing—that there must have been two wild types of the European races, one a moufflon very like the Corsican, if not identical with it; the other a lost race, long-tailed with horns spiring in a double circle. The latter would be an immediate prototype of the old heath race, the former of the diminutive short-tailed sheep with crescentic horns, as the genuine old Highland, the Shetland, and cognate races.18 Can you help me at all in this enquiry? The horns upon a stuffed head of a Shetland ram now with Leadbeater are uncommonly moufflon-like, & so is a skull marked Indian in B.M.,19 which may however have been brought from India without being Indian! Do you happen to remember the description in some French work (20 years or more ago) of Ovis arkar, from the mountains bordering on the Caspian? Blasius figures the horns, but without giving dimensions, or referring to the original description, which I decidedly remember having read in French, but I cannot now find out where.20 You will have seen my essay on origin of goats, since writing which I have come to know the true C. caucasica, which is widely different from ægagrus, & akin to pyrenaica. 21

Yours ever truly, | E. Blyth—

P.S. I will write again on secondary sexual differences in mammalia.

CD annotations

CD note:

Blyth abstract of letter on Sexual S.

Sheet I. on Bustards nuptial plumage confined to males. In plover & sandpipers common to both sexes, except in Ruffs and Reeve, but in latter female does undergo some change, with trace of frill.— case of do in likewise [interl] polygamous Rallidæ

Sheet II. seasonal changes in Gulls & Terns common to both sexes.

Sheet II. p. 2. Canines in Walrus*—perhaps seals [interl]— Do not differ in terrene carnivora—

— — p. 3. Canines in Ruminants

No canines in Hollow-Horned Ruminants [vary] in Antelope— Larger in ♂ Camel & Guanaco

Narwhal & Mastodon ohioticus

Not much in other monkeys

Sheet III. p. 4. some male Deer have nuchal ruff & larynx increase in size during breeding season. no change of colour during breeding season in Deer

— — p. 4 sexual colouring of Antelopes

Sheet IV. Case of allied genera, in one of which birds undergo great seasonal change *in both sexes [interl] & not in other.—

Footnotes

Bibliography

Birds of the world: Handbook of the birds of the world. By Josep del Hoyo et al. 17 vols. Barcelona: Lynx editions. 1991–2013.

Blasius, Johann Heinrich. 1857. Naturgeschichte der Säugethiere Deutschlands und der angrenzenden Länder von Mitteleuropa. Vol. 1 of Fauna der Wirbelthiere Deutschlands und der Angrenzenden Länder von Mitteleuropa. Brunswick: Vieweg und Sohn.

Blyth, Edward. 1841. An amended list of the species of the genus Ovis. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 7: 195–201, 248–61.

Correspondence: The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt et al. 29 vols to date. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985–.

Descent: The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. By Charles Darwin. 2 vols. London: John Murray. 1871.

Jerdon, Thomas Claverhill. 1862–4. The birds of India; being a natural history of all the birds known to inhabit continental India, with descriptions of the species, genera, families, tribes, and orders, and a brief notice of such families as are not found in India, making it a manual of ornithology specially adapted for India. 2 vols. in 3. Calcutta: the author.

Lydekker, Richard. 1898. Wild oxen, sheep and goats of all lands, living and extinct. London: Rowland Ward.

Nowak, Ronald M. 1999. Walker’s mammals of the world. 6th edition. 2 vols. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Sykes, William Henry. 1834. Catalogue of birds (systematically arranged) of the Rassorial, Grallatorial, and Natatorial orders, observed in the Dukhun. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 3: 597–9, 639–49.

Variation: The variation of animals and plants under domestication. By Charles Darwin. 2 vols. London: John Murray. 1868.

Vogt, Carl. 1864. Lectures on man: his place in creation, and in the history of the earth. Edited by James Hunt. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts.

Summary

Discusses sexual and seasonal differences in the plumage of birds and coats of mammals.

Remarks upon variations in the form of the canine tooth between the sexes in mammalian groups.

Plumage of allied species of plover.

Asks CD’s help with work on unimproved domestic animals.

Letter details

- Letter no.

- DCP-LETT-5418

- From

- Edward Blyth

- To

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Sent from

- unstated

- Source of text

- DAR 83: 34, 150–1, DAR 84.1: 26–7, 138

- Physical description

- ALS 10pp AL inc? †

Please cite as

Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 5418,” accessed on 18 April 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-5418.xml

Also published in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vol. 15